To say that 1974 was a year of change and challenge for David Bowie and his fans is an understatement as extreme as the lurid outfits he’d worn as his just-abandoned alter ego, Ziggy Stardust. The incubator for the evolution was Bowie’s U.S. tour that year, which began in Montreal on June 14 — 40 years ago this weekend.

In July of 1973, at the peak of his success, Bowie unexpectedly retired Ziggy — the character and vehicle he’d ridden to fame after nearly a decade of trying. In the months that followed, he abandoned his band, his home, and the city (London) and country that spawned him. By the spring of 1974, he’d ditched the zipperhead haircut, platform heels and vivid glam fashions that he, more than anyone, had brought to the mainstream. And by the end of that year he’d basically abandoned rock and roll altogether.

While the Beatles had acclimated the even-then largely complacent rock audience to changes of sound and vision, at the fateful age of 27, Bowie — fueled by exploding creativity, success and not least the white powder to which he’d become addicted — would try the patience of even his most dedicated fans, producing music that wasn’t dauntingly strange and experimental (that would come later), but instead too normal and everyday for many of his fans: the R&B that saturated FM radio at the time. That style might have seemed exotic to a Brit, but it was the exact sound that most American rock fans were trying to escape.

That the two studio albums associated with the tour — Diamond Dogs, released in March of ’74 and already a departure, written, produced and performed largely solo by Bowie as it was, and musically more subtle than its comparatively garish predecessor, Aladdin Sane, and Young Americans, put out a year later and featuring Bowie’s first U.S. Number 1 single, “Fame” — made him into a star in America is perhaps the strangest twist of all.

The 73-date tour, too underwent a stylistic change every bit as tectonic as the one Bowie’s music was undergoing. At its outset, the Diamond Dogs tour was by far the most extravagant and expensive rock outing ever mounted: designed by Broadway veterans Jules Fisher and Mark Ravitz and choreographed by Toni Basil, it featured a towering set depicting the post-apocalyptic city in which the loosely conceptual album was based. It included a catwalk that lowered from the rafters to stage level and a cherry-picker that lofted Bowie 40 feet above the first dozen rows of the audience (and occasionally failed to bring him back). But after 10 weeks of shows, due to expense or boredom, he abandoned the set and the setlist, going for a more stripped-down presentation and an overhauled R&B sound.

“I sunk myself back into the music that I considered the bedrock of all popular music: R&B and soul,” Bowie recalled to writer David Buckley years later. “I guess from the outside it seemed to be a pretty drastic move. I think I probably lost as many fans as I gained new ones.”

It’s one of the most drastic image/sound changes in the modern era, and it was just the beginning of the transformations Bowie would make over the next several years. Over the course of the tour, Bowie would drive himself, his band and his audience to the brink: himself to the edge of exhaustion via the physical challenges of the show, overwork and drug abuse; his band to the brink of its musical abilities, energy and salary requirements; his audience to the brink of its patience.

“I went to the Diamond Dogs show [in June] expecting something like Ziggy Stardust,” said fan John Nielson, who caught both incarnations of the tour in Detroit. “And then in October I expected to see something like Diamond Dogs, and it was the soul revue. It might as well have been a completely different artist.”

The basis for the tour and its initial extravagant set lay in Diamond Dogs‘ post-apocalyptic world of street urchins and nefarious characters, like Halloween Jack; the album was the end result of an unsuccessful attempt to create a rock musical from George Orwell’s 1984, which had been blocked by Orwell’s widow. While the album — and its classic lead single, “Rebel Rebel,” which was finishing a Top 5 run in the U.K. at the time Bowie arrived in New York on April 11 — retained elements of the aborted musical, like Ziggy Stardust, it’s a loose concept album not bound to a straight storyline; the songs act as signposts around which listeners can create their own narrative.

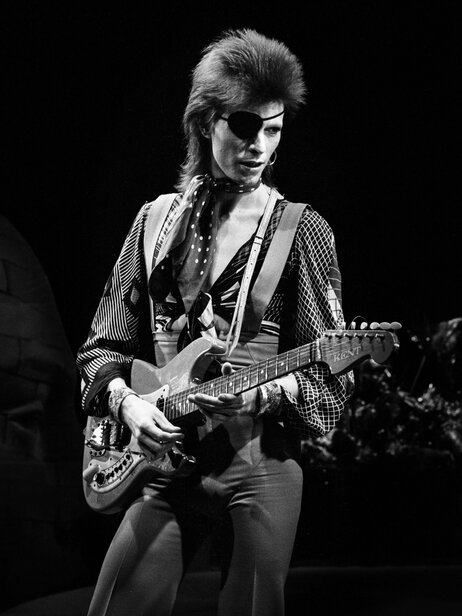

David Bowie, in February of 1974 in the Netherlands.

Gijsbert Hanekroot/Redferns

“I had in my mind this kind of half Wild Boys/1984 world, and there were these ragamuffins, but they were a bit more violent than ragamuffins,” Bowie told Buckley. “They’d taken over this barren city, this city that was falling apart. … I had the Diamond Dogs living in the streets. They were all little Johnny Rottens and Sid Viciouses, really.”

That storyline carried over to the show. Framed by towering skyscrapers, Bowie moved from one elaborate scenario to another: He performed “Sweet Thing” from the catwalk as it gradually lowered to the stage floor; was projected over the audience via the cherry-picker as he sang “Space Oddity” into a red telephone microphone; French-kissed a skull during “Cracked Actor”; sang “Time” behind a giant hand festooned with blinking light bulbs that dropped to reveal Bowie inside a neon light box; performed an elaborate walking mime during “Aladdin Sane” very reminiscent of Michael Jackson’s world-famous Moonwalk, unveiled a decade later (Jackson attended one of Bowie’s shows in Los Angeles in September). The Ziggy-era platforms and costumes were replaced by a suave new Bowie, clad in an Yves St. Laurent suit and flat shoes, with a bright orange but calm soul-boy haircut.

Bowie’s new band was equally state-of-the-art. Herbie Flowers — who’d worked with Bowie since the mid-’60s and played the timeless bassline on Lou Reed’s “Walk on the Wild Side” — and drummer Tony Newman were veteran British session musicians who’d played on Diamond Dogs. Virtuoso pianist Michael Garson and backing singer Geoff MacCormack (aka Warren Peace) remained from Bowie’s 1973 band. Classically trained New Yorker Michael Kamen — a future Grammy-winning and Oscar-nominated film composer whose scoring work for the Joffrey Ballet had impressed Bowie — was enlisted as musical director. Kamen brought along two musicians from his former rock bands: future superstar jazz saxophonist David Sanborn and 22-year-old guitarist Earl Slick, who would work with Bowie many times in the coming decades, and also performed on John Lennon and Yoko Ono’s Double Fantasy.

The latter got a call from Kamen one day in April and was told he’d be hearing from an important musician he refused to identify.

“I get a phone call from the Bowie people the next day and they set up an audition — which is the weirdest f—-ing thing I’ve ever done in my life,” Slick, who speaks in a Brooklynese as rapid-fire as his solos, recalls. “David’s personal assistant meets me at RCA Studios in New York, and she walks me not to the control room, which is dark, but into the main studio. I get out my guitar and I hear a voice with an American accent saying, ‘Hey, how ya doin’? Put the headphones on. We’re gonna play you some tracks, just play along.’ I say, ‘What key are they in?’ He says, ‘Don’t worry about it.’ And he just starts rolling tape! I’m playing over tracks from Diamond Dogs, which [hadn’t been released yet] — I’ve never heard these songs, I don’t know what I’m doing.

“I’m out there for maybe 15 minutes and there’s a little bit of chatter between me and this American guy — who turns out to be [longtime Bowie producer] Tony Visconti — and about two minutes later Bowie walks in,” he continues. “We hung out for about half an hour, fiddling around with guitars. His assistant says, ‘We’ll call you in the next couple weeks.’ But the phone rang the next day and they said, ‘If you want it, you got it.'”

Over the following weeks, the band — filled out by saxophonist Richard Grando, percussionist Pablo Rosario and backing singer Gui Andrisano — worked up radically new arrangements of Bowie’s catalog, which were strongly influenced by New York City nightlife. Bowie had become friends with guitarist Carlos Alomar — a veteran of James Brown’s and Wilson Pickett’s bands, as well as the Apollo Theater’s house band — who took the singer to the Apollo and elsewhere to see The Temptations, The Spinners and Marvin Gaye; he also hit Latin clubs and other nightspots in the city’s budding disco scene, as well as rock haunts like Max’s Kansas City.

That influence was immediately felt not just in the soul covers the band played on the first leg of the tour — Eddie Floyd’s 1966 classic “Knock on Wood,” the Ohio Players’ 1968 song “Here Today and Gone Tomorrow” — but also in the reinventions of Bowie’s catalog, which went far beyond the blistering power-trio rock of the Ziggy era. “Aladdin Sane” received a Latin treatment driven by Garson’s manic piano; “Jean Genie” slowed to a lounge crawl on the verses and completely dispensed with its signature riff; even the brand-new “Rebel Rebel” got a looser tempo and jazzy backing vocals.

“He was hanging out a lot in New York,” fan Kathy Miller recalls. “I remember seeing him and his entourage snowed in during a blizzard at a [April 22] New York Dolls show at Kenny’s Castaways, and friends of mine saw him at Puerto Rican discos, black discos. So it was not such a shock to New Yorkers that he gravitated toward that kind of music.”

After dress rehearsals at the Capitol Theater in Port Chester, New York — “Two days? Maybe more, because that was one complicated f—-ing thing,” Slick says — the entire production headed up the Northway to Montreal for the first of what would ultimately be 30 dates of the initial leg of the Diamond Dogs tour. Not surprisingly, the opening night had more than a few rough spots. The sound system was distorted, and the catwalk plummeted dangerously to the stage floor with Bowie on it, a problem that happened more than once.

The kinks were gradually worked out and the tour carried on across the Northeast and South, playing major venues — Cleveland’s Public Auditorium for two nights, Detroit’s Cobo Hall, Nashville’s Municipal Auditorium — but also many smaller, less-likely markets and theaters, like Charleston, West Va.; Dayton and Toledo, Ohio; Norfolk, Va. While most nights went off without a hitch, the complexity of the set continued to cause problems.

At the Norfolk show, Rob Holland, then 14, recalls, “I remember the cherry-picker got stuck: it moved for a minute and then it moved again to the side of the stage, but then it got stuck and he had to get off of it.”

On at least one other night, the cherry-picker extended to its full length but failed to retract, leaving Bowie stranded over the audience. “When he finished the song he had to shimmy along the [cherry-picker’s hydraulic] arm back to the stage,” Tony Visconti writes in the David Live liner notes. “Members of the audience were standing on their seats trying to grab him and pull him down. On that night, this was perceived as part of the show: David made it seem to look that way, climbing back in a dramatic, purposeful way.”

While many were dazzled by the stage and the theatrics, some weren’t so impressed. “I really liked the set, but I’ve always felt it would have been a much better show if they had really exploited it, doing Diamond Dogs semi-theatrically and really using the staging,” John Nielson says. “He did use it for ‘Sweet Thing,’ but the rest of the time it just sorta loomed in the background. It was a kind of wasted opportunity.”

Brad Elvis, formerly of The Elvis Brothers and currently in The Romantics, caught two shows in Toledo and Dayton, Ohio. “It got a good reaction, but it wasn’t like pandemonium,” he remembers. He and a couple of friends did, however, spend time with Bowie and bandmembers at a hotel-room party after the Dayton show — where he witnessed the growing R&B influence first-hand.

“There were about five other people in this cramped little room, and they had this big boombox,” he says. “Kind of dancey R&B was playing, and one of the [backing singers] was showing Bowie these dance moves. Everybody’s dancing, having fun, getting loose, except us — we’re watching, wide-eyed.”

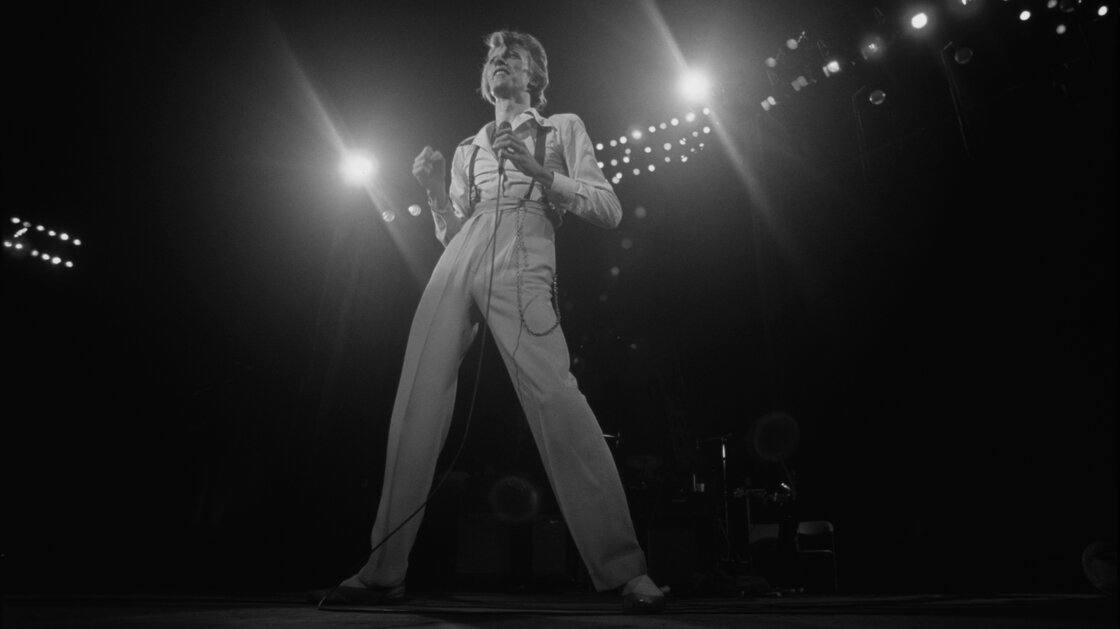

David Bowie onstage at Madison Square Garden in New York City July 20, 1974.

Ron Galella/WireImage

As the tour’s first leg reached its home stretch in mid-July, with a run of six shows at Philadelphia’s fabled Tower Theater, the show was beset by a problem that had nothing to do with technology. Eager to get a live album on the market before the tour concluded, Bowie’s then-manager, Tony Defries, arranged to have the Tower shows recorded. Live recordings ordinarily entitle the musicians to a much higher fee than Bowie’s touring group was receiving (Slick recalls getting $300 per week), but Defries attempted to sidestep that issue.

“Back in the day, if you were recording, there were two microphones on everything: one would go to the [venue’s] sound, and one would go to the [mobile recording] truck,” Slick says. “At soundcheck, I didn’t think anything of it, but Herbie picked up on it right away. Tony Defries was one of the biggest f—-ing shysters on the planet, and [earlier that day] I had gotten a letter pushed under my hotel door offering me $300 basically to give my rights over. Not long after that, Herbie is on the phone with everybody saying, ‘This is bulls—-, we’re not gonna do this.’ Basically, with Herbie being the spokesperson, we said we ain’t going onstage until we get an agreement for x amount of money, period. They agreed to it, we signed it — and we didn’t get paid, so we sued David. We won, but it took a long, long time to get the money. I know David pitched a serious fit on Herbie, and I think he was kinda s——y for a couple of days, but then everybody got past it.”

Still, the bad vibes come through on David Live, released in the fall. Bowie’s voice is strained and the band, while competent, played better on other nights of the tour, as bootleg evidence shows.

The tour wrapped with two nights at Madison Square Garden, Bowie’s first performances at the venue.

“The stage show got a lot of advance buzz,” Kathy Miller remembers. “We couldn’t wait to see this set, and it really lived up to the expectations, it was gorgeous. But the [cherry-picker] reminded me of a telephone repairman — it was not glamorous; it was actually very Spinal Tap! It looked dangerous and rickety — there really was a sense of, ‘Oh my god, is this going to work?'”

“It was quite an unbelievable, unbelievable headache, that tour, but it was spectacular,” Bowie told Buckley. “It was truly the first real rock and roll theatrical show that made any sense. A lot of people feel it has never been bettered. It was something else, it really was.”

Despite its enormous expense and problems, the tour helped drive Diamond Dogs to Number 5 in the U.S. — by far his highest chart position at the time.

In early August, many of the bandmembers gathered in Philadelphia to begin work on the album that would become Young Americans, which is where the R&B transformation truly took hold.

While Bowie had originally intended to work with the house band at the city’s Sigma Sound — which had spawned hits by The O’Jays, Lou Rawls, The Three Degrees and Harold Melvin & the Blue Notes — they were unavailable due to a scheduling conflict, and he brought in several members of his touring band, as well as some key new collaborators who would play a huge role in the album: Alomar; his wife, soul singer Robin Clark; and a young friend, future R&B superstar Luther Vandross. The latter two, along for the ride, were playfully riffing on one of the songs in the studio; Bowie loved it and had them sing on nearly every song. It was the first high-profile work of Vandross’ career.

Although Bowie was raised on American R&B, like most British musicians of his generation — and he’d even performed James Brown’s “You Got to Have a Job” during the Ziggy Stardust era — the resulting sessions produced music that resembled nothing he had ever done before. Alomar, Sanborn and the singers became Bowie’s primary musical foils, often working in a soulful call-and-response role with him on songs like “Fascination” (a rewrite of Vandross’ composition “Funky Music”), “Somebody Up There Likes Me” and the title track. Bowie, fueled by cocaine, taxed the energy of the musicians by working largely from 11 p.m. until the late the following morning.

(The album sessions, which resumed in November and again in January, featured two more star appearances. Bruce Springsteen, whom Bowie had admired since seeing a New York performance in 1972, visited the sessions but ultimately did not contribute to Bowie’s cover of his “It’s Hard to Be a Saint in the City.” More fruitful was a visit from Bowie’s new friend John Lennon, who was lured to the studio by being asked to contribute to Bowie’s excruciatingly overblown over of Lennon’s “Across the Universe,” but ended up co-writing “Fame” — a studio creation conjured from Bowie’s cover of the Flares’ 1961 R&B hit “Footstompin’.”)

While he dismissed the album as “plastic” not long after its release, Bowie later recanted. “In 1976 I spouted some nonsense about the album being ‘synthetic radio stuff.’ I don’t believe that for one moment now,” he told Buckley. “I was living and breathing soul and R&B at this time. I listened to nothing else. It became America for me.”

While Bowie’s cocaine appetite was severe before the ’74 tour began, it had escalated dramatically by the time dates resumed at the end of the summer. A brief second leg of the tour kicked off with a seven-night run at the Universal Amphitheatre in Los Angeles, and it was at this time that director Alan Yentob interviewed Bowie and filmed the shows for the hour-long BBC documentary . The Bowie on display there is an unsettling sight: fidgety, awkward and alarmingly thin and pale, he’s intelligent but remote and removed; at other times he’s in the throes of cocaine paranoia, wondering whether his car is being followed, sniffling and licking his gums. At one of the Universal concerts, captured on the A Portrait in Flesh bootleg, Bowie speaks to the crowd almost exclusively in a bizarre pseudo-Italian accent, making inscrutable jokes.

The Bowie that emerges in the documentary is so odd and otherworldly that it convinced Nicolas Roeg he’d found the perfect person to portray the alien in his forthcoming film The Man Who Fell to Earth, which would mark Bowie’s feature-length debut the following year.

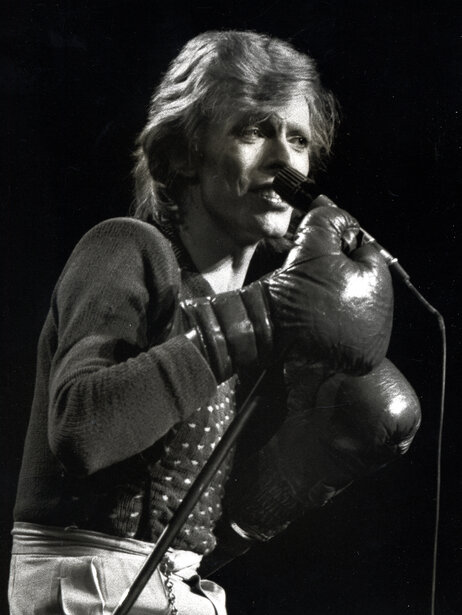

While the set and setlist were retained for the Universal shows and a few more Southwest dates, the show was completely reconceived during a break over the second half of September. The city set was abandoned and the new staging relied on dramatic lighting and clever use of silhouettes (a 50-foot shadow of Bowie was projected onto a screen behind the stage for “1984”). Bowie changed his wardrobe and hairstyle yet again, adopting a sweeping pompadour, jackets embellished with shoulder pads, a thick checkered tie, suspenders, baggy pants and occasionally a cane.

Most of all, the band was overhauled to recreate the Young Americans sound: Alomar, Vandross, Clark and three other singers who performed on “Young Americans” were brought on board; and Bowie recruited his fifth different rhythm section in a year’s time: rock-solid drummer Dennis Davis (who, like Alomar, would be with Bowie for the rest of the decade) and bassist Emir Ksasan. Garson was made musical director, and Bowie’s revamped backing band became the opening act for the tour, cruising through a 30-minute set of smooth takes on songs like “Stormy Monday,” The O’Jays’ “Love Train” and Vandross’ “Funky Music” before concluding, strangest of all, with a lite-R&B treatment of Bowie’s own “Memory of a Free Festival,” a hippie anthem from his 1969 Space Oddity album. The crowds hated them.

While the Bowie set that followed kicked off reassuringly with either “Rebel Rebel” or “Space Oddity,” it then headed straight into R&B and ballad territory: a funked up version of “John I’m Only Dancing,” a samba-fied “Sorrow,” “Changes.” Rocked-up versions of “Moonage Daydream” and “Diamond Dogs” were thrown in, but a huge dollop of the unreleased Young Americans was aired on most nights — along with “Footstompin’,” which would form the basis of “Fame” — before the shows concluded with a one-two punch of “Suffragette City” and “Rock and Roll Suicide.”

The tour, beginning on October 5th in St. Paul, Minnesota, soldiered across the Midwest, East and South over the ensuing seven weeks, setting up residencies in several cities — seven nights at New York’s Radio City Music Hall, six in Detroit, three in Boston — before closing in Atlanta on December 1st. Bowie’s precious voice, ravaged by cocaine abuse and months of touring, was hoarse on at least a few occasions. Audiences were nonplussed at best by the new production.

“I’d bought a really glam outfit: A top with bell sleeves, skin-tight jeans and mile-high, red-leather platform boots,” recalls Lisa Seckler-Roode, who attended one of the Radio City shows. “People came dressed as Ziggy Stardust, with the Aladdin Sane lightning bolt on their faces. It was sort of like Wigstock: I remember the cops looking at the crowd and shaking their heads.

“But when Bowie came out in that suit,” she sighs, “I mean, he looked glorious but it was such a change that the crowd was totally thrown — the atmosphere was just, ‘Huh? What’s he doing now?’ In retrospect it was very bold move, but the initial reaction was really confused. I remember going to school the following Monday: ‘How was the show?’ ‘It sucked!'”

Nielson recalls a similar reaction in Detroit. “The soul show threw everyone, since the album wasn’t out yet and there was a lot of new material,” he says. “The audience reaction was more polite than [hostile], for the most part, because obviously everyone loved Bowie and gave him the benefit of a doubt. But it was muted appreciation at best and probably some quiet disapproval.”

At least one musician onstage shared the sentiment. “I gotta be honest with you, I wasn’t terribly thrilled with it,” says Slick, whose guitar roars out at a searing volume on bootlegs during the rare occasions he got the spotlight. “[During the opening set] there wasn’t a whole lot for me to do. For the Bowie set I was back on it, but even with that, the way it was being played wasn’t rock and roll anymore.”

Bowie’s , taped early in November during the Radio City stint, is fascinating, mixing new, (relatively) old and obscure: the band charges through a fast “1984,” Bowie straps on his Ziggy-era 12-string acoustic as the singers groove for “Young Americans,” and concludes with the still-unreleased “Footstompin’.”

While Bowie is in strong form, if a bit hoarse, when performing, his interview with Cavett could function as an anti-cocaine ad. He fidgets relentlessly with a cane he used as a prop during the performance, sniffles and appears completely ill at ease — at one point Cavett asks him if he’s nervous. “Um … oh, let’s carry on talking,” he replies. “Don’t ask me that. Otherwise I’ll wonder, you see. I’d rather not know if I’m nervous until …” he trails off.

During the interview, he’s perhaps most cogent when explaining his rationale for his new look and sound. “We did the Diamond Dogs tour and took it from New York to Los Angeles, and I felt that that was enough, really. Rather than come back with the same thing, I wanted to give myself an opportunity just to work with the band. … I got a lot of fulfillment from working in productions like Diamond Dogs or Ziggy Stardust. But now that I’m working with just a band and singing, which is something I haven’t done for years, I’m finding a new kind of fulfillment.”

Judging from the reaction of fans and the tepid-to-negative reviews the show received, Bowie’s audience was not yet ready for that new kind of fulfillment.

Somehow, from such unpromising origins, from such a turbulent, tumultuous, drug-addled year — one that saw Bowie poised for enormous success yet opting not just to challenge his audience but almost to defy it — after 73 concerts and against daunting odds, the tour helped accomplish the ultimate goal: breaking David Bowie in America. Diamond Dogs reached Number 5 on the Billboard charts. David Live went to Number 8. The Young Americans album hit Number 9 and the title track was his first U.S. Top 40 single, peaking at 29. And “Fame” was a global hit single, became Bowie’s first U.S. Number 1 and made him into a superstar. In 1975, he relocated to Los Angeles, launched his movie career, and became an all-around entertainer who appeared on both Soul Train and Cher.

(Despite its now-legendary status, Bowie’s 1974 tour is tragically ill-documented. Apart from fan-filmed super-8 footage, the only video documentation of the Hunger City set that has surfaced is Fisher and Ravitz discussing this scale model in the 1996 . (the Cracked Actor documentary shows frustratingly little of the stage). Likewise, apart from a that aired in a VH1 Legends episode, no footage from the soul concerts has emerged, although the Cavett show at least documents some performances. While some sources say that Bowie filmed rehearsals and the Garden shows, and the VH1 footage suggests there’s more somewhere, Slick says he has no recollection of any shows being filmed.)

And while many, including this writer, consider Young Americans to be his weakest 1970s studio album, that is hardly an insult. In terms of influence, it’s hard to know where to begin: virtually every artist bearing a trace of white soul since its release — from Robert Palmer to Duran Duran, from George Michael to Robbie Williams and far beyond — owes more than a “sho’nuff” and some hair gel to it.

Ultimately, Young Americans and the Soul Tour were way stations: like everything Bowie had done before, he ingested and used them as a foundation for what came next. In this case, it was the pioneering ice-funk of Station to Station, arguably one of his two best albums, and one that paved the way not only for thousands of artists who were influenced by it, but the brilliant wave of experimentation that followed over the next five years: Low, Heroes, Lodger and Scary Monsters. But that’s another story …

Sources: David Buckley’s stellar liner notes to the deluxe editions of Diamond Dogs and Young Americans, and Tony Visconti’s for David Live; Kevin Cann’s David Bowie: Any Day Now, The London Years 1947-74; Roy Carr and Charles Shaar Murray’s David Bowie: An Illustrated Record; Chris Carter’s “; Chris O’Leary’s “; and especially Roger Griffin’s “.

Special thanks to Ira Robbins, Jennifer Kennedy, Julian Stockton and especially everyone who took the time to be interviewed for this article.