While many artists put their homies on, very few put them first.

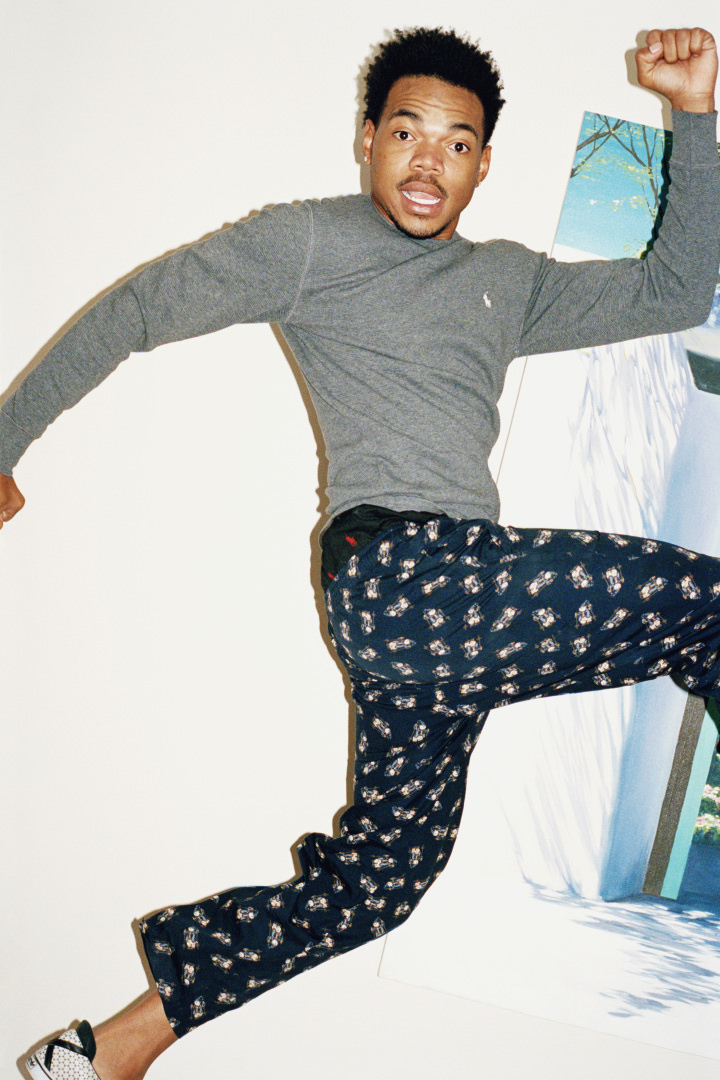

Chancelor Bennett is posted on the back patio of an Airbnb rental overlooking the Hollywood Hills. He’s wearing a White Sox hat; he’s smoking a blunt; he’s holding court with his friends. He is Chance The Rapper, and Chance The Rapper is a famous rapper, or at least a reasonably famous one. He’s not quite Lil Wayne-famous, but he’s famous enough to have recorded a song with Lil Wayne. People whisper his name when he walks into a room.

This is a celebrity that the 21-year-old has held since at least 2013, when his freebie album Acid Rap exploded across the internet. It’s a remarkable tape, really, one of those rare, oh-shit full-lengths where a young artist manages to present a fully formed personal vision—in this case, an optimistic but uncompromising depiction of his Chicago upbringing, and a warmly nostalgic sound. In the months since, he’s toured aggressively, dropped a handful of well-received tracks on SoundCloud, and landed a few high-profile collaborations with Wayne, Skrillex, Justin Bieber, and James Blake. (In late 2013, he and Blake even announced plans to move into a house and record a collaborative album, though this fizzled out at the last moment for reasons Chance himself seems unclear about.)

It’s an old story by now. Rapper makes raps, raps blow up, fame follows, famous followers follow that fame, followers follow those famous followers and more of the fame follows, etc. What makes Chance interesting—or at least what makes him especially interesting—are the moves he has chosen to make in the months since those dominos began to fall, and the moves he has chosen not to make. He’s remained oddly noncommittal about his future after Acid Rap. No announcing a million-dollar, major-label deal. No self-righteous, keep-it-indie counter-announcement about rejecting those deals either. And, much to the devastation of his still-budding fan base, not even the slightest hint of a new solo full-length.

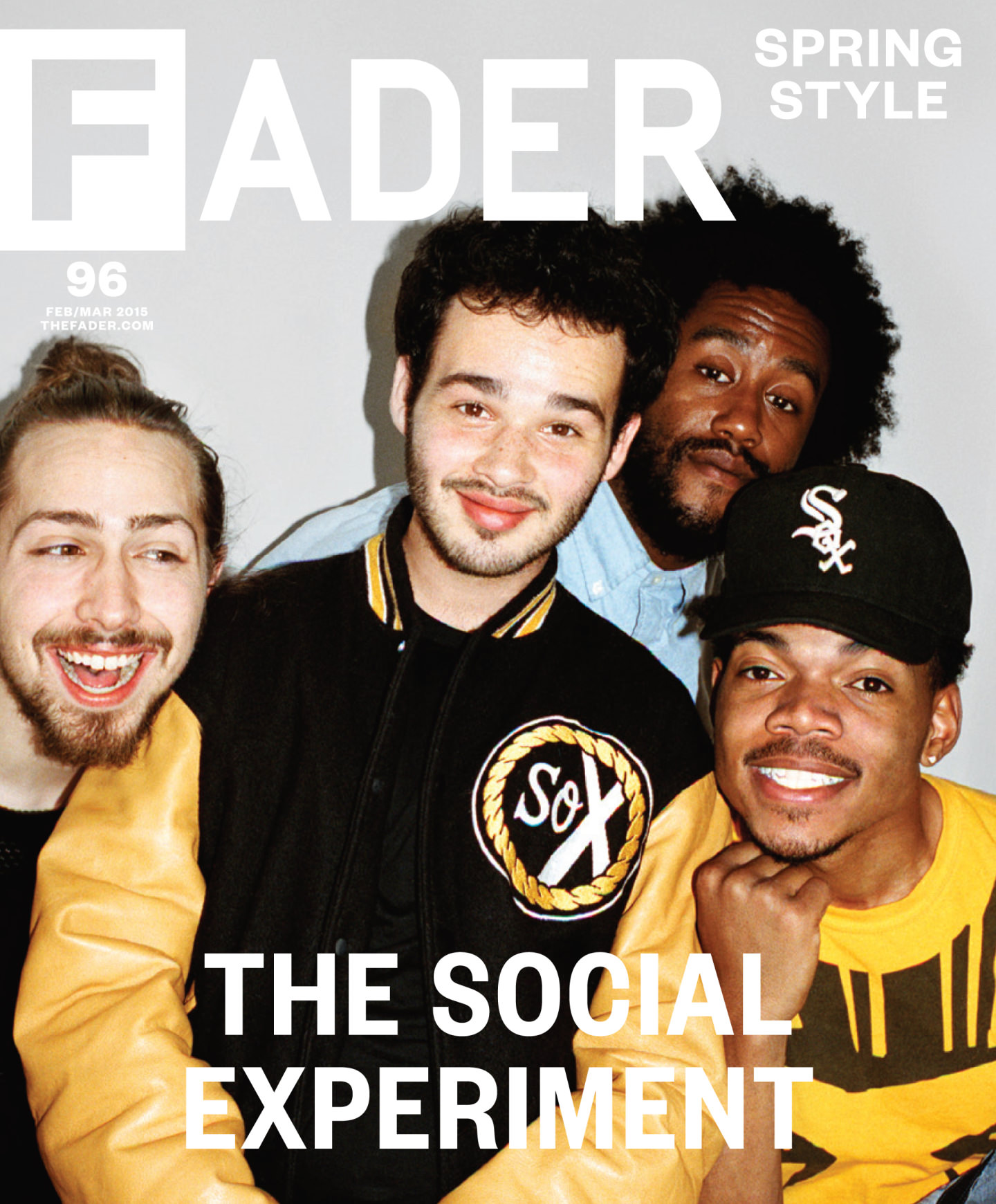

When Billboard ran an article with the headline “Exclusive: Chance The Rapper Reveals New Album, Surf” in October 2014, it seemed like his fans’ thirst was soon to be quenched. And it will be. Except Surf is not a Chance The Rapper album. It’s not even a rap album, really. It’s the sprawling debut by Donnie Trumpet & The Social Experiment—The Social Experiment being the four-member songwriting and production unit that began as Chance’s backup band on his 2013 tour of the same name. Donnie Trumpet, a 21-year-old born Nico Segal, is the member of this collective who—you guessed it—plays the trumpet. Chance is another member, but, notably, he’s just another member. He’s buried himself in a group setting, deferring a shot at becoming a more-than-reasonably-famous rapper in favor of an uncentered, cross-genre collaboration with his friends.

Chance The Rapper and Donnie Trumpet

Chance The Rapper and Donnie Trumpet“Every day I literally wake up and figure out when I’m gonna be able to go to the studio. In the meantime, I’m trying to do some very fun shit.” —Chance The Rapper

And so his friends are with him here on this sunny afternoon, on the same porch, overlooking the same hills. Nico is present, as is the 27-year-old producer/engineer Nate Fox, and the 23-year-old producer/keyboardist Peter Wilkins, aka Peter Cottontale, both of whom comprise the other half of The Social Experiment’s creative core. (Their live drummer, Greg “Stix” Landfair Jr., is back home in Chicago.) Though they’ve all united with the common goal of finding pure joy in music-making—and sidestepping some of the industry expectations that so often stifle that joy—a lot of that translates to just hanging out.

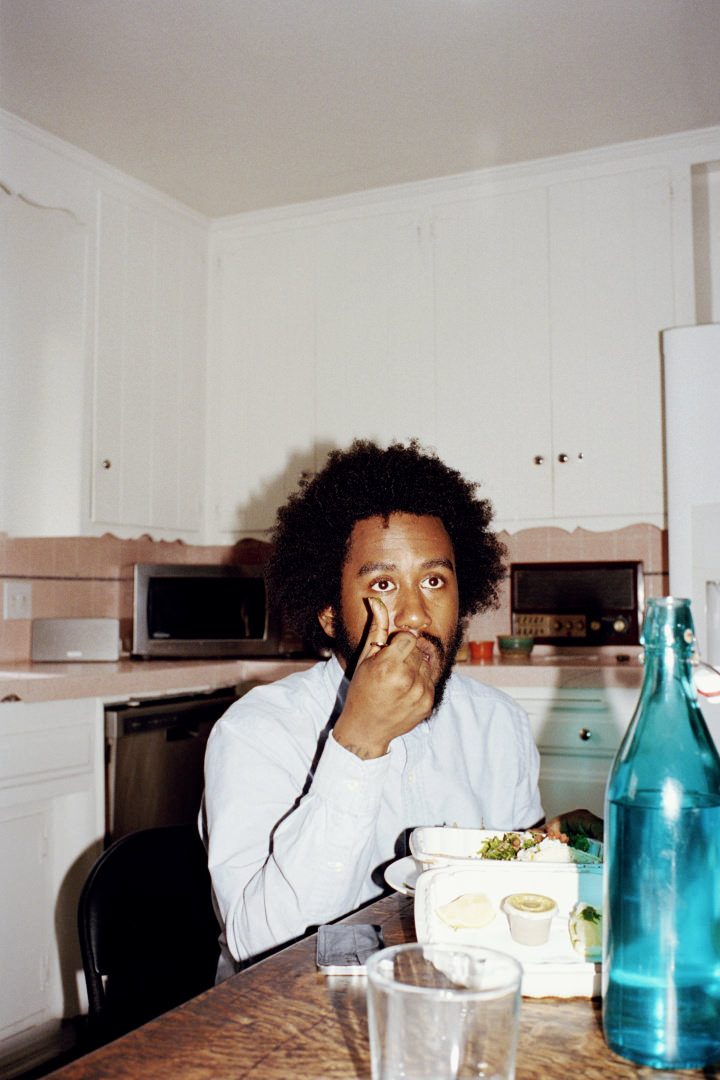

The night before, Chance had been rushed to the hospital due to an inexplicable fever, but he was sent home with a handful of Tylenol and a prescription for some bed rest. It seems to have done the trick: now, he’s moving in lightweight hummingbird flutters as he talks to everyone and no one in particular. The rest of the crew is looking slightly worse for the wear, though, having been up until the crack of dawn putting some finishing touches on Surf. Nate slept in his car outside the studio, and it shows in his tangled “Jesus hair,” as Nico calls it. Nico’s own bedhead seems to be permanent; Peter’s afro is equally scraggly. If your first guess seeing them wasn’t “studio rats,” you might mistake them for college students at the tail-end of exam season.

But such is the cost of the Experiment. Nico and Nate have taken up permanent residence here in L.A.; Chance and Peter are still technically based in Chicago, though they’ve been bouncing back and forth while making Surf. “I like L.A.,” Nico says. “I play basketball every day and walk on mountains and shit. I’m really just locked up in the studio no matter where I am, so it’s nice to wake up to sunshine everyday. Chicago sometimes plans your day for you.”

Shortly after the blunt burns out, the cipher reconvenes inside, around the island in an aggressively modernist black-and-white kitchen. Nate gravitates to his Macbook, which controls a flatscreen across the room, and starts playing partially finished tracks through the TV. Chance acts a lot like he raps: wide-eyed and hyperactive for the most part but also prone to abrupt moments of deep reflection. Nico, whose befuddled but deliberate tone makes him seem perpetually on the cusp of either a punchline or a revelation, talks about how he’s been reading Confucius: “He was a hella observant fellow.” The same might be said about Peter, who mostly watches quietly.

Peter Cottontale

Peter Cottontale Nate Fox

Nate Fox“I just want to do something fun today,” says Chance, and everyone in the room begins to float ideas and inside jokes. “You wanna go to Venice Beach?” Nico asks. “There’s basketball courts.” Chance nixes it: “I feel you, but they’re always overcrowded.” He waits a beat, then adds: “With The Game’s posse. I’ve seen The Game there twice, taking over the whole gym area of the park, doing hella pull-ups.” Nico responds: “I bet The Game can do a lot of pull-ups.”

Periodically, they’re all drawn out of this conversation and back to the music, which fills the room with formless shards of muted trumpet and angelic harmonies. Nico imagines a Kung-Fu video treatment for one nearly completed song. Chance drums along on the tabletop with a pair of kitchen knives, then a bottle opener, then his knuckles. Later, he’ll absentmindedly break out into a brief, mumbled half-freestyle in a Dropout-era Kanye drawl: Damn this house is so maahdern/ Such a maahdern house…

Then the Los Angeles fun-day hypotheticals continue: How far is Six Flags? Do you need a driver’s license to ride a jet ski? Go-Karts? Laser tag? Roller rink? The Price Is Right? The Museum of Contemporary Art? “Every day I literally wake up and figure out when I’m gonna be able to go to the studio,” Chance explains. “And in the meantime, I’m trying to do some very fun shit.” Right now, they’re all having more than enough fun just imagining. By the time they finally take a vote and make something close to an official call—a trip to an indoor trampoline park—everyone is too fried to execute the commute, let alone the actual act of bouncing on trampolines. Instead, they decide to stay in, drink some mimosas, and watch Will Smith in Ali.

Acid Rap was an album about memory by an artist with a vivid one. As a student of rap history, Chance wore his influences clearly: the eagerness of early Kanye, the syllable-compounding of Eminem, the jazz cadences of West Coast tongue-twisters like Freestyle Fellowship and The Pharcyde. The production was expansive, touching some of the brightest points in Chicago music’s past, from Curtis Mayfield to juke music. Yet Chance proved to be more than a young revivalist playing dress up in his predecessors’ suits. Instead, he tore up the fabrics and restitched them into a new style, one suited to his voice’s precise Woody the Woodpecker squawks and, as Chance puts it on “Good Ass Intro,” sporadicity and fucking pure joy. As a writer, Chance proved wise beyond his years, with a knack for measured sociopolitical commentary. On the half-hidden and wholly chilling bonus track “Paranoia,” he addresses the murder rate in his hometown, calling not just for peace but also compassion from onlookers: We know you’re scared/ You should ask us if we’re scared too.

The tape instantly turned Chance into a critical darling. Acid Rap was voted #5 in the Village Voice’s annual industry-wide year-end Pazz and Jop poll, placing right behind Beyoncé and making it the poll’s highest-ranking rap mixtape of all time. (Previously, that honor was held by Lil Wayne’s Da Drought 3, which came in at #35 in 2007.) It attracted a diverse audience, racking up millions of plays online, and while it was never released to retail, an unsanctioned CD bootleg sold so well that it still managed to hit #63 on the Billboard Hip-Hop Album charts.

Labels swarmed, and Chance respectfully declined their offers, choosing instead to continue with an amorphously defined indie approach of selling merch but not music, touring vigorously and doing whatever the hell he wants in the time off. So far, that strategy is working. “I’ve met with every A&R, VP of A&R, president of the labels, CEOs. I know all these people,” he says. “I’ve had a lot of advice from people [in the industry] who wouldn’t give me that same advice today. It’s not even that they have any ill will towards me because I didn’t take their advice at the time. They’re almost like, ‘Keep going. You’re in uncharted territory, and you’re helping to shed light on what [the future of the business] will look like, and we’re all curious.'”

If his internet-fueled ascension seems sudden, it’s only because of how old-world Chance’s grind had been at first. His story starts in Chicago and stays there for a few years. He honed his skills at YOUmedia, an after-school creative program for teens based out of the public library. He organized events and linked with student bands. He pushed CDs the old-fashioned way, first winning over the kids from his own high school, then expanding outward. “I was right on State Street, asking people to listen to my mixtape and promising them that it was hotter than they thought it was,” he remembers. “The only time I sold CDs was when I got them to actually put the headphones on.” 10 Day, released in 2012, was the last and most professional of his four high school mixtapes, a loose conceptual project based around Chance’s real-life suspension for smoking weed, and it solidified his status as a local favorite. (It also featured a pair of beats from Peter and a somber solo courtesy of Nico.) By that point, technology was catching up to Chance’s hustle.

“It’s so dope that I was able to be the age that I was when I was coming up,” he says. “People were just realizing how to use YouTube on a DIY level. Twitter, SoundCloud—all that shit was just starting to pop when I was making 10 Day. A lot of people out of Chicago were able to flourish because it was so new.” While the out-of-town press has often propped Chance up as an alternative—or even antidote—to the more street-centric drill music of fellow Chicagoans Chief Keef and Lil Durk, he remains adamant that they are all part of the same scene. “It’s all the same shit,” he says. “We got all the same fans in the city. We’re playing the same venues. Musically, our sounds are different, but we really need each other in order to exist. We need the idea that rapping is important for people to help us to continue to thrive.”

Also integral to this scene was Kids These Days, a seven-piece alt-rock/jazz-rap/everything-else band of high school friends that counted both Nico and Stix among its ranks, as well as rapper and frequent Chance collaborator Vic Mensa. Their 2012 full-length, Traphouse Rock, was co-produced by Wilco’s Jeff Tweedy and Beastie Boys engineer Mario C. Though not without its charms, it was an overwhelmingly referential project, a case of too many talents cramming a narrow space with all the music they’d ever loved. Radiohead bumped up against Chi-town fast-rap legends Crucial Conflict; funk metal morphed into funeral jazz. Still, through that cacophony you can quite clearly hear the DNA of The Social Experiment, that same ethos of defining your influences and then pushing them to their logical extremes.

Donnie Trumpet

Donnie Trumpet“Donnie is so unique in his ability to transform the tone and sound of the trumpet. It’s almost like a lead guitar, like he’s Slash.” —Nate Fox

Peter Cottontale came up kicking around that same constellation of young Chicago musicians—and with similar genre-bending instincts—making beats for both Vic and the jazz vocalist Lili K while playing keys in the rock band Mathien. Nate, however, stands as a bit of an outlier in the group. He’s not from Chicago but a small town outside of Pittsburgh, and he’s the eldest by far, nearly 30 in a crew where everyone else is just barely old enough to drink. He studied studio engineering and has a decade of more traditional hip-hop beatmaking under his belt, for the likes of Machine Gun Kelly and, recently, Big Sean. He met Chance at SXSW in 2012 and began sending him instrumentals shortly thereafter. Four of those beats landed on Acid Rap, and Nate was quickly absorbed into the fold. Like the others, he seems grateful for the creative freedom that comes with being in the band. “The most incredible thing is that Chance is so open to whatever everyone else thinks,” Nate says. “He’s willing to put in all of his resources, all of his cards, everything on the table to make it work, to make it whatever [Nico] thinks of.”

“Surf is Nico’s project,” Chance says matter-of-factly, back on his borrowed porch as night begins to fall. “He was working on it when we decided to be The Social Experiment, so we decided that his project should be first.” This might seem like an extraordinarily humble gesture on Chance’s part—while many artists put their homies on, very few put them first. But in talking to him, you don’t get the impression that he ever gave it a second thought. He came up in a small, tightly knit creative community and is now instinctively using the cultural capital he’s earned to sustain that same circle. It’s only revolutionary when you look at it through the lens of a bent industry that has built its business model around severing stars from the scenes that birthed them. In a better world, it would be a given that making music for the sake of the music comes before marketing yourself, that community is more valuable than celebrity.

Donnie Trumpet

Donnie TrumpetAfter Ali, the four musicians head to The Fox Hole, Nate’s West Hollywood studio, located in one of those ghostly, two-story hybrid strip malls/professional buildings common to L.A. Chance wants to preview some tracks from Surf, and his TV speakers aren’t cutting it anymore. The record is a whole lot to digest in any setting. In some ways, it’s a logical extension of what Chance was doing on Acid Rap, with the most organic elements of that album teased further out of the typical rap production framework and blown out to their most grandiose extremes. Nico’s robust solos anchor most tracks, but they frequently run parallel to double-time raps. Lush neo-soul hooks crumble into blippy house.

These are the sounds of a pack of band kids who hold Miles Davis, Rich Homie Quan, and Kirk Franklin in similarly high esteem and who have been given carte blanche to touch on all of those influences and more at once. They like to define their target audience as “grandmas and babies,” and that makes some sense—the record roughly splits the difference between spirituals and lullabies. It’s also so densely packed with sounds and ideas that it’s hard to imagine either of those demographics being able to detect the nuances. Or, as Chance suggests, it might just take a little time.

“A song should have a different meaning for at least the first three times you play it,” he says. “That’s the biggest thing to it—adding onto the track, just making as many different sounds and small peculiarities and accents that make the song what it is. Like on [Michael Jackson’s] ‘P.Y.T.,’ that little wah wah-a, that one little sound that Kanye ended up sampling for ‘Good Life’ only happened once in the song. You wouldn’t know that unless you listened to the record over and over again and found that one piece that you like.” It’s almost as if Chance and his friends are aiming to reverse-engineer the act of beat-digging. Where earlier generations of hip-hop producers foregrounded small fragments of music from the past, The Social Experiment buries new ones for the future.

“The most incredible thing is that Chance is so open to whatever everyone else thinks. He’s willing to put in all of his resources, all of his cards, everything on the table to make it work.” —Nate Fox

Chance The Rapper

Chance The RapperWhen Surf comes on, everyone moves. Peter spins around in his swivel chair. Nico mimes a slap-boxing match with Nate before sliding into a mechanical Bernie dance, barefoot on the hardwood floor. Chance closes his eyes and bobs his head. At one point he steps out for a cigarette, but when a track hits a particularly complex vocal section, he swivels most of his body back around the apparently not-so-soundproof door, leaving just one arm out with the smoke, and shouts, “Eight part harmony!” He’ll later brag about how, during one Chicago session, they recorded 610 different tracks, so many they needed to take them to a better-equipped L.A. studio to finish the song.

With Surf, The Social Experiment tends to prioritize this stacked sonic architecture over traditional song structure. It’s music to sink into. “Donnie is so unique as a musician in his ability to transform the tone and sound of the trumpet for the song,” Nate says. “It’s almost like a lead guitar, like he’s Slash. Every song, the trumpet is different—it’s a different tone, a different style.” The workflow is ever-changing too, with no one contributor stuck in a single role. Chance contributes on the production side, and Nico has been using the project as an excuse to flex his talents as a percussionist too. “It’s really never been like ‘Peter lay keys, Nico lay some horns, Nate put down some programmed drums, Chance write a rap verse,'” says Chance.

This communal approach extends well past the main quartet. Surf is a collaborative project without borders, and most tracks are tangled and packed with different vocalists and instrumentalists who aren’t immediately identifiable. “Every record has like 50 people on it,” Chance explains. “The idea is to make a singular, four-minute-and-30-second song that feels like a year’s worth of music.” As he plays the album, he seems to strategically skip around certain tracks as if to conceal the presence of more prominent stars. When he does mention collaborators by name—like fellow Chicago spitter Noname Gypsy or the budding Atlanta singer Raury, who appears on Chance’s favorite track from the project, an airy number called “Windows”—he tends to refer to them as “my friends.”

Surf demands repeated listens, which is not exactly what their manic listening session today affords. As a vocalist, Chance floats in and out. Sometimes he’ll be buried under a stack of sounds, just one voice among many. Elsewhere he’s at the forefront, singing in a hush or rapping like the room is running out of oxygen. Either way, he comes across as just another of the many small peculiarities in the mix. “People hear what they wanna hear,” says Nico. “If they only wanna listen to the songs with Chance The Rapper, they’re gonna have to listen to the whole project cover-to-cover because I’m not gonna tell them which songs [he’s on]. The important thing is just to listen. Listen to the music, then send it to your grandma.”

The Social Experiment

The Social Experiment Chance The Rapper

Chance The RapperThe next day, Chance, Nico, and Peter have found more fun. They’re shooting hoops on Venice Beach with a wider crew, including trombonist J.P. Floyd, another ex-Kids These Days player who they describe as an unofficial member of The Social Experiment. Nico is wearing the same shirt from the day before and visibly trying harder than anyone else on the court. Chance throws up bricks but seems not to care. Peter wanders off in the hopes of finding a record shop he’s heard about but returns only with a pack of Pocky.

It’s an unusually overcast Thursday for Los Angeles, even in December, so the courts and the boardwalk are mostly empty, give or take a small smattering of old heads who have probably been hanging there for decades. The Game is nowhere to be found. The only rappers milling about are the ones pushing their CDs hand-to-hand. One of them, who looks to be in his late twenties, hones in on Chance’s Sox hat and comes over to announce that he, too, hails from Chicago. He introduces himself as Ish Illa. They exchange blocks like business cards, and he condenses his life story as a reformed gang banger into a sales pitch. Chance is remarkably patient in the midst of this hustle, even though his face does register a hint of visible disappointment after he asks the man, “Who you fuckin’ with from the city?”—their city—and Ish responds, “To be honest, man, nobody.”

Eventually, Ish breaks out the old Coby discman for the last-ditch taste test. After about a minute of listening, Chance’s eyes bug out and dart around the table. “This shit cold!” he says. “I cannot even stunt! No jokes!” Chance insists that he has no cash on him, and after much bartering, Ish finally agrees to give him a CD for free and walks off. Chance’s enthusiasm remains, though he admits, “I feel like a dick because I definitely have five dollars on me.”

He turns to Nico and asks, “You know what memory just came back to me? Do you remember at Oak Street Beach, before the Kids These Days show at The Metro, when you, me, and J.P. stood at one of the little underpass things? You guys pulled out your horns, and I was freestyling over it, and we were selling tickets? That shit was hot, bro!”

As they reminisce on the distant past of just a few years ago, Ish swings by a second time. Having now completely dropped his salesman’s demeanor, he shouts, “Hey, one more thing! I know you Chance The Rapper!” The next day Chance will tweet “listening to Ish Illa” with a link to the rapper’s SoundCloud. Ish will respond in kind, posting the Acid Rap cover to his Instagram with the caption “God just used the music that he gave me to touch even a famous rapper!!” It looks like Chance may have just made a new friend.