Last February, Rap-a-Lot heir James “Jas” Prince filed a lawsuit—for the third time in about as many years—seeking what he believes he is owed by Cash Money Records for Drake’s tremendous success.

As the legend goes: Jas, whose father is legendary label founder James “J.” Prince, was hoping to find a place for himself in the family business. While in college, he came across Drake’s brown-and-beige MySpace page. Impressed by what he heard, Jas brought the the then-unknown Toronto boy to his then-friend Lil Wayne. The rest, as they say, is history.

“I’m owed something,” Jas told The FADER in March, speaking on the phone while mounted atop a horse on his family’s ranch in Houston. “I deserve it. It’s not like I’m asking for something that’s not mine.” (The case is ongoing, a spokesperson for Prince told The FADER.)

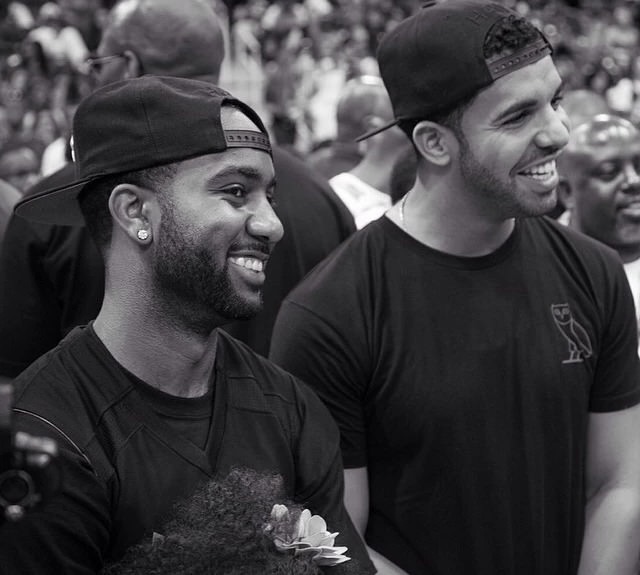

Today, Jas is 27 and still in the music business, developing artists under the banner of his own promotion company. It appears he remains friends with Drake. Below, he tells the story of how Drake and Wayne met, and how Drake got into the Cash Money deal he no longer loves.

JAS PRINCE: Back in 2006, I was in school but I had told my dad that I wanted to get into the music business. He told me that I had to look for the hottest thing, to find someone who had a buzz. MySpace had a music explore page at the time, and you could see who was trending by zip code or whatever. I ran across all types of artists on there, like Soulja Boy, but Drake was the one that caught my eye. He was ranked number one or two on the unsigned trending artists list. His page just said that his name was Drake and he was from Toronto, and there was a picture of him and he had a video on there for the song “Replacement Girl” with Trey Songz. You know how MySpace had a little radio player on the right side? He had a couple of songs on there, and I was listening to him like, Damn, he’s pretty dope.

So I kind of slid in Drake’s messages and was like, “Hey, what’s up? I’m Jas Prince.” I let him know who I was and who my father is, and I told him that I wanted to make him famous. And he was like, “I get that a lot but, whatever you say.” We kept in contact and I brought his music to my dad. He didn’t get it. He was like, “What do you see in this?” Because rap to him was more gangster hip-hop music than someone rapping and singing. But I was like, Well, he has a buzz.

Then I threw a New Year’s party for Wayne in Houston. The next day, he asked me to take him to my jeweler, Exotic Diamonds on Westheimer. I got him a car and he was in my front seat and we were just riding down Westheimer, and I’m always thinking of business, so I’m like, you know what, lemme play some Drake while he’s in my car. So I put on “Replacement Girl” and look over and see that he’s bopping his head, and I’m like Okay! So I put on another song—an “A Milli” remix Drake did. Wayne was like, “Who’s this?” I was like, “Oh, this nigga Drake that you told me you didn’t like.” Drake had been sending me music, and I was sending him records he was not supposed to have at the time to rap over, to kind of create a buzz. When Wayne heard his “A Milli” remix he was like, “How did he get this track?” At that time, Drake definitely had an advantage on some people.

I played Wayne another song called “Brand New,” and I’m like, “He sings, too.” Wayne is like, “Hold up, man, this dude is really fucking dope.” He’s like, “Where is he at?” I told him in Canada, and Wayne was like, “Let’s fly him here right now.”

So I called Drake, and he was like, “I’m getting a haircut, let me call you back,” but I was like, “Hold up, somebody wants to talk to you.”

I give Wayne the phone and Wayne was like, “Yo, what’s up?” Drake was like, “Who is this?” And Wayne said, “It’s Weezy.” Then he gave me the phone back.

Drake was like, “Was that really Wayne?” You know how Drake talks. I told him I was gonna fly him into Houston because Wayne wanted to meet him, and we flew him in the next day. He was being courted by other people at that time, too. But I told him, “I’m gonna make you famous, I believe in you and I’m going to give it my all. I’m gonna do it, I have a plan.”

We flew him into Houston. Drake and I had been talking a lot—I was really blowing him up, we was always texting—but that was my first time actually meeting him. When I brought him to Wayne, Wayne was nonchalant. He didn’t really speak to Drake at all, so Drake was like, “Does he not like me?” Before Drake got there, all Wayne was listening to was Drake—and I never really see him listening to nobody but himself, so that was different. But then Drake arrived and it was silent treatment. I felt like he was timid because Drake was so dope, he was competition.

Eventually Wayne was like, “I’m about to go to Atlanta tonight, why don’t y’all ride with me on the bus?” So we got on the bus with 50 other people, squished up ’cause Wayne was such an asshole that he had his clothes in all the bunks so nobody could sleep and it’s about a 15-hour ride on the bus. When we got there, we went to the studio. That’s when Drake first recorded the original “Forever” and “Stunt Hard.” A couple of weeks later that got leaked, and that was the beginning of Drake.

Then we started working on the So Far Gone mixtape. Wayne was on tour around that time. One night, I think in San Francisco, we went up on stage before him and the crowd is yelling, “Jimmy! Jimmy! Jimmy!” And we all were looking at each other like, who the fuck is Jimmy? You got 15,000 people yelling Jimmy and we don’t know who the hell Jimmy is but they have Drake’s picture on the screen. Finally he’s like, “That’s my character on this show called Degrassi in Canada.” I was like, “What the fuck, you act, too?”

Cortez Bryant is Wayne’s manager. When we figured out that we wanted to work on the project, Cortez flew down to Houston and sat with me and my dad and we talked about how we were going to do it—50/50, with him and Wayne and me and my dad, Young Money and Young Empire. But then things got quiet. We got a little call that they’re moving on, things are happening be we ain’t really got not deal together. My dad extended a hand and put a call out to Birdman and Slim, because those are his people over there. We went to meet in LA with Cash Money and Cortez and we all structured the deal that we had. They was trying to do it without me. It seemed like Drake didn’t know too much about what was going on, the business part was kind of between us.

[The Fader]