The digitisation of the music business, coupled with an almost complete absence of standards, has taken an already complex licensing and collection environment and exploded it into a data shit storm.

Processing it is providing a challenge beyond most smaller companies and equally challenging to major corporations and large collection societies alike.

Logic implies that collecting rights together into chunks sufficiently big enough for the digital distributors to manage would appear sensible.

Yet today some companies, Apple being one example, seem to prefer to deal with thousands of licensors.

Why is that? Given the complexities of the rights ecosystem, it makes no sense.

At the same time the music industry’s largest rights owners have been handed an opportunity to steal a march on smaller companies by simply leveraging their size, not the quality of their repertoire.

“WHERE IS THE REALISTIC COMPETITION FOR AMAZON, YOUTUBE OR APPLE?”

The legislative position in the US and the EU does not assist in making anything easier.

The modern mantra of competitiveness makes it illegal to conduct sensible discussion between interested parties.

At the same time it does nothing whatsoever about the monopsony enjoyed by the digital licensees, who invariably will set the terms of any negotiation by wielding the hammer of being the only buyer.

Where is the realistic competition for Amazon, YouTube or Apple, for instance?

All the while, the US rate courts are hobbling the free market activity of BMI and ASCAP and making preposterous judgements that prejudice the interests of composers and songwriters.

Thank goodness, then, that the US administration seems to be waking up to the fact that the regulatory control over the negotiation of rights is archaic and not fit for purpose, especially in the land of the free (there’s a pun in there somewhere).

The lifeblood of the commercial music industry has always been generated by innovative, imaginative, insurrectionist small players.

We all know the lists… Ralph Peer, Roy Acuff, Erteguns, Moss, Blackwell through to Domino’s Laurence Bell and XL’s Richard Russell etc.

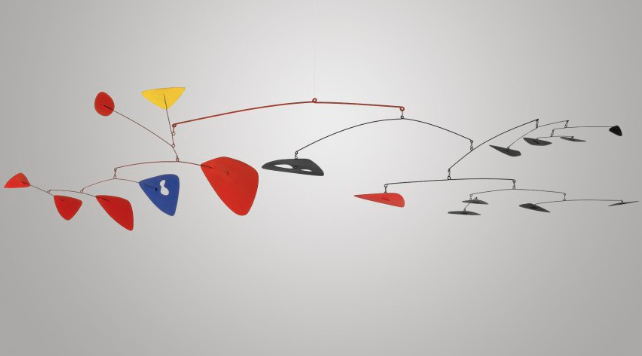

I have always felt that the interdependence of the different parties within the commercial music value chain achieved an unlikely balance of interests, as seen in Alexander Calder’s elegant mobiles (pictured, main).

However, as with those beautiful mobiles, placing too much weight on one section risks the stability of whole piece.

Major publishers are now clearly endeavoring to obtain a higher return for the same use that smaller companies are able to obtain.

There is no blame in that, but it risks destroying the precious seed corn that this industry has always needed in order to grow.

“THIS FEBRILE ATMOSPHERE, OF ALL PARTIES REACHING FOR AN EVER-LARGER SLICE OF THE PIE, HAS LED TO A FRACTIOUS MUSIC MARKET.”

As for the major record companies, they are taking so much bread off the digital table that the indies have to survive on the crumbs.

Again, no blame there, it is their job to maximize their interests, but the damage it could do to creativity is inestimable.

The historic acceptance of the interdependence of the different sectors of our industry seems to be disappearing.

On top of the differing return of identical uses referred to above, we now have the astonishing precedent of a major record company saying in court that it has no interest in the benefit of its artists… REALLY!?

This febrile atmosphere, of all parties reaching for an ever larger slice of the pie, has led to a fractious market, where all participants are at each other’s throats – encouraged in part by a drift away from collective licensing.

My fear is that the basic infrastructure of licensing and distributing the revenues created by young music creators and entrepreneurs will eventually cease to exist.

Without the security of this stable structure, the role of the independent entrepreneur may no longer be viable, as we witness the conscious freezing out of opportunity for emerging talent.

The monopsony I refer to, enjoyed by the major digital players, is in danger of being replicated within the music industry.

An independent publisher or record company may soon find that the only way of enjoying the revenues that the majors receive is to license through them. That is the end of independents and independence.

There is hope. Merlin has found a formula that allows indie record companies to achieve decent digital deals, notwithstanding those licensees who still try to avoid the collective organisations.

On the publishing side the UK publishers have set up IMPEL, which echoes the formation of Merlin. IMPEL is now attracting many US indie publishers and is going from strength to strength.

While the members of Merlin and IMPEL may be indies, their respective repertoires match any major in terms of history, breadth, diversity and importance.

“AN INDEPENDENT PUBLISHER OR LABEL MAY SOON FIND THAT THE ONLY WAY OF ENJOYING THE REVENUES OF THE MAJORS IS TO LICENSE THROUGH THEM. THAT IS THE END OF INDEPENDENTS – AND INDEPENDENCE.”

I’m also encouraged by SESAC and HFA offering both mechanical and performance licensing solutions in the US and the acceptance by the EU that it is sensible for PRS, GEMA and STIM to pool resources, rather than see it as some sort of monopolistic plot.

Whilst not perfect by any means, these new developments at least indicate a recognition that new solutions are required to solve the business problems of individual music companies.

It is essential that creators and smaller companies continue to encourage collective organisations to remain effective and competitive.

Without them our entire revenue ecosystem has the potential to come crashing down.