There are those who believe Pandora’s recent aggressive expansion moves have been born out of ambition and market opportunism. And there are those who believe they have been born out of desperation.

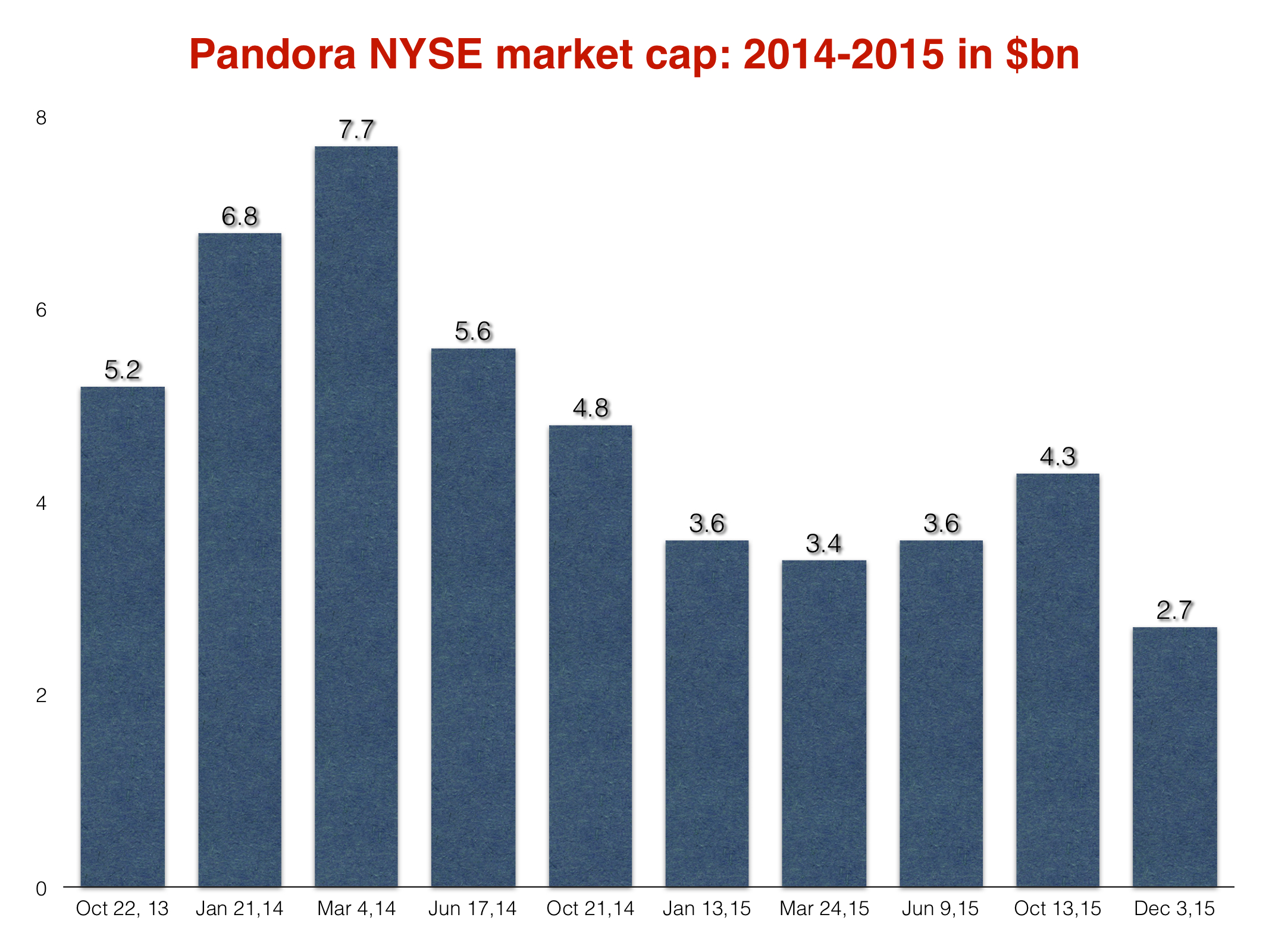

The latter camp appear to be dominating consensus on Wall Street, judging by the worrying decline in the streaming music company’s NYSE share price over the past 18 months.

Pandora’s stock hit an all-time high in Q1 2014.

As you can see below, in late February last year, its share price stood at $37.42.

This was a good era for the non-interactive Spotify rival.

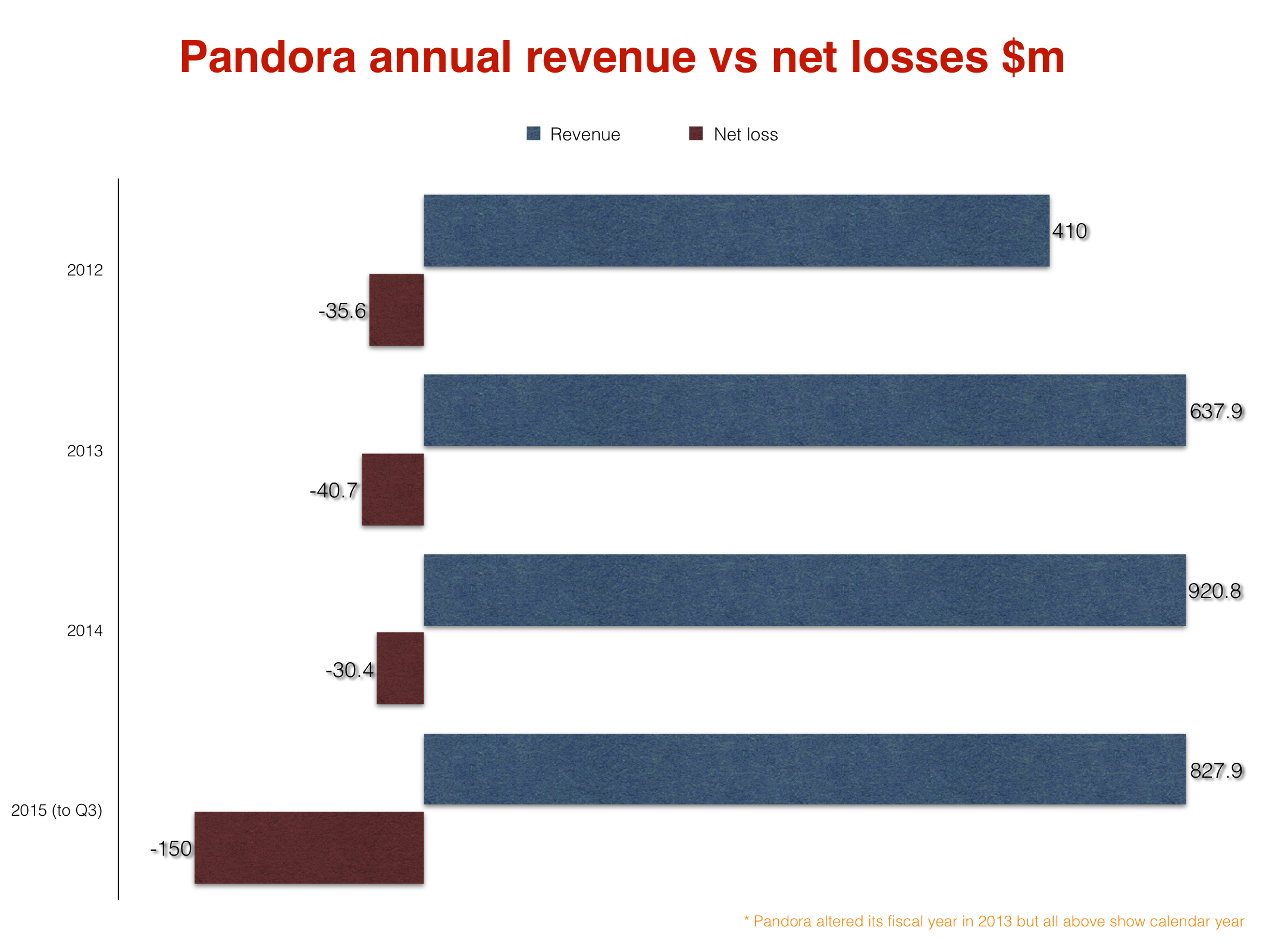

Pandora had very recently posted FY 2013 revenue growth of 56%, to $427.1m.

Investors and analysts felt patient enough to forgive steep net losses in the name of rapid growth – especially when those steep losses narrowed by $10.3m to just over $30m in FY 2014.

Now, though, that patience appears to be running low on gas.

At close of play last night (December 3), Pandora’s stock price had sunk to $12.63.

That’s almost exactly two-thirds down on its value in Q1 last year – a decline of more than 66%.

As a result, the market cap value of the company today stands at $2.7bn.

As recently as Q1 last year, it towered above $7.7bn.

Pandora’s stock crashed by a further 11.5% yesterday alone, with investors clearly spooked by the company’s decision to raise $300m through a controversial convertible debt offering, and what that might mean for its future.

The debt raise will effectively see Pandora borrow extra money from investors, with the intention to pay them back with equity down the line.

It has raised suspicions that the company, which had $442.6m cash in the bank at the end of Q3 this year, is preparing for bad news.

The Copyright Royalty Board will decide later this month on the webcasting rate that the likes of Pandora must pay recorded music rightsholders in the US from 2016-2020.

Pandora is attempting to bring down the average stream payout rate from $0.0014 to $0.0011, while SoundExchange is demanding a move to $0.0025. The dial can move only one way.

Pandora’s decision to raise debt funds comes after a spate of expensive moves by the company, all tethered to two hopes: (i) placating music rightsholders in order to gain more expansive licenses; and (ii) increasing the number of revenue streams coming into the company:

- In May, Pandora acquired music data / intelligence service Next Big Sound, a former Spotify partner, for an undisclosed fee;

- Five months later, in October, it purchased independent ticketing agency Ticketfly for $450m;

- Later that month, it paid out $90m to the major labels and ABKCO to settle a lawsuit regarding the historical play of pre-1972 tracks on the platform;

- In early November, it signed an expanded licensing deal direct with Sony/ATV – one which very likely allowed for interactive use of song copyrights;

- And in mid-November, it snapped up $75m of key assets from Rdio as the Spotify rival headed into bankruptcy

This week’s debt raise, plus the CRB decision and Pandora’s expenditure in the past six months, has combined to rattle Wall Street – exacerbated by the fact that Pandora suffered a dip in active monthly listeners in Q3 (down 1.6% to 78.1m), a metric that was expected to grow.

And then there’s the issue of net losses. Investors are clearly getting frustrated with Pandora’s seeming inability to stop the rot.

Although Pandora is on course for its first ever $1bn fiscal year in revenue terms, it hasn’t continued 2014’s trend of narrowed losses this year. Not by a long chalk.

In the first nine months of 2015 alone, the firm lost a wince-worthy $150m – five times its annual loss from last year.

Can Pandora’s expansion into new sectors and a global, interactive streaming service (should rightsholders license it) save its business model?

Can its recent attempts to pour scorn on the freemium on-demand setup of Spotify really convince labels and artists to switch loyalties?

Do its new acquisitions make sense?

Clearly, the jury is out on all of these questions – while optimism amongst the investment community teeters on the brink.