Stu Bergen’s career has thrown up one sanity-saving truth on a number of occasions: “There’s always a peak after a valley.”

In mid-1993, Bergen, then an on-the-up promotions exec at Epic Records, accompanied one of the most powerful rock music radio programmers in the US to Lollapalooza.

His mission: to convince the unnamed media gatekeeper that Rage Against The Machine could cut it in the mainstream.

Cue the band’s arrival on stage: butt-naked, gags covering their mouths, tackle out, and bodies daubed with letters in protest at moral pressure group PMRC.

Mr. Radio Bigshot quietly looked at the floor.

Bergen (pictured) also has many fond memories of helping break Oasis in the US in the mid-nineties.

His smile becomes slightly less beaming, though, when he recalls the time Liam Gallagher flat-out refused to board his flight to an arena show in Chicago.

“You learn a lot going through these things,” Bergen tells MBW today from his skyscraping Broadway office in New York.

“When something feels like the end of the world, there’s often good news around the corner. Either that, or you just need a change of strategy.”

As President of International at Warner Music Group, like all of his major label colleagues, Bergen has observed a rather more serious ‘valley’ unfurling over the past ten years.

Unlike titter-worthy anecdotes about rock star calamities, it’s one noticeably missing a punchline.

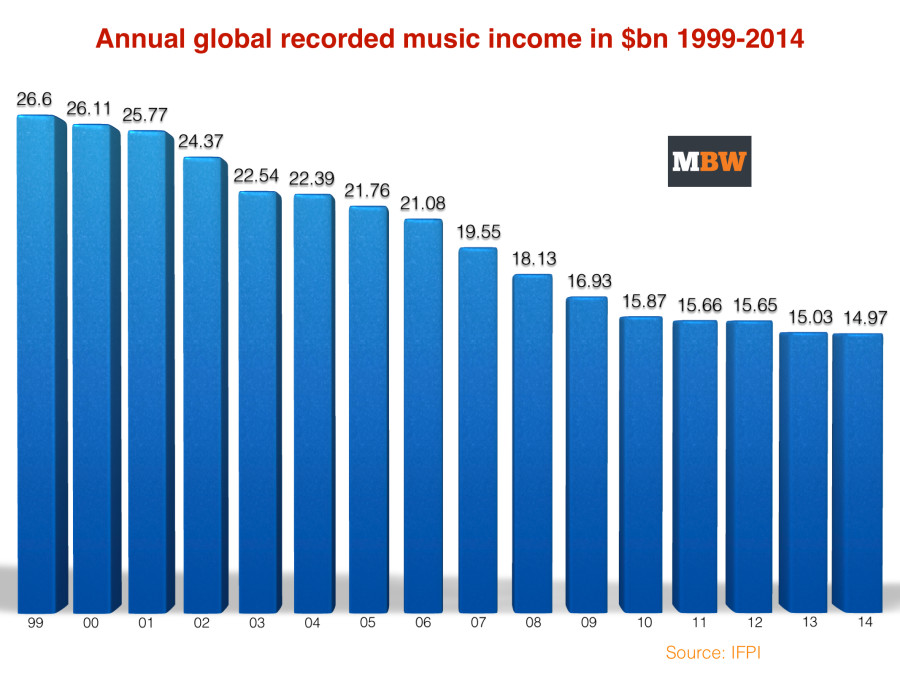

Since the exec arrived at WMG in 2006, following stints at Columbia and Island Def Jam, global recorded music industry revenues have declined by a painful $5bn.

When you factor in inflation, according to MBW analysis, that decline gets even more scary: topping $7bn.

Yet when MBW grills affable New Jerseyite Bergen on his key objective – maximising WMG’s success outside of the US and UK markets – he’s positively upbeat.

Bullish, even.

And when you look at the statistics, you start to understand why.

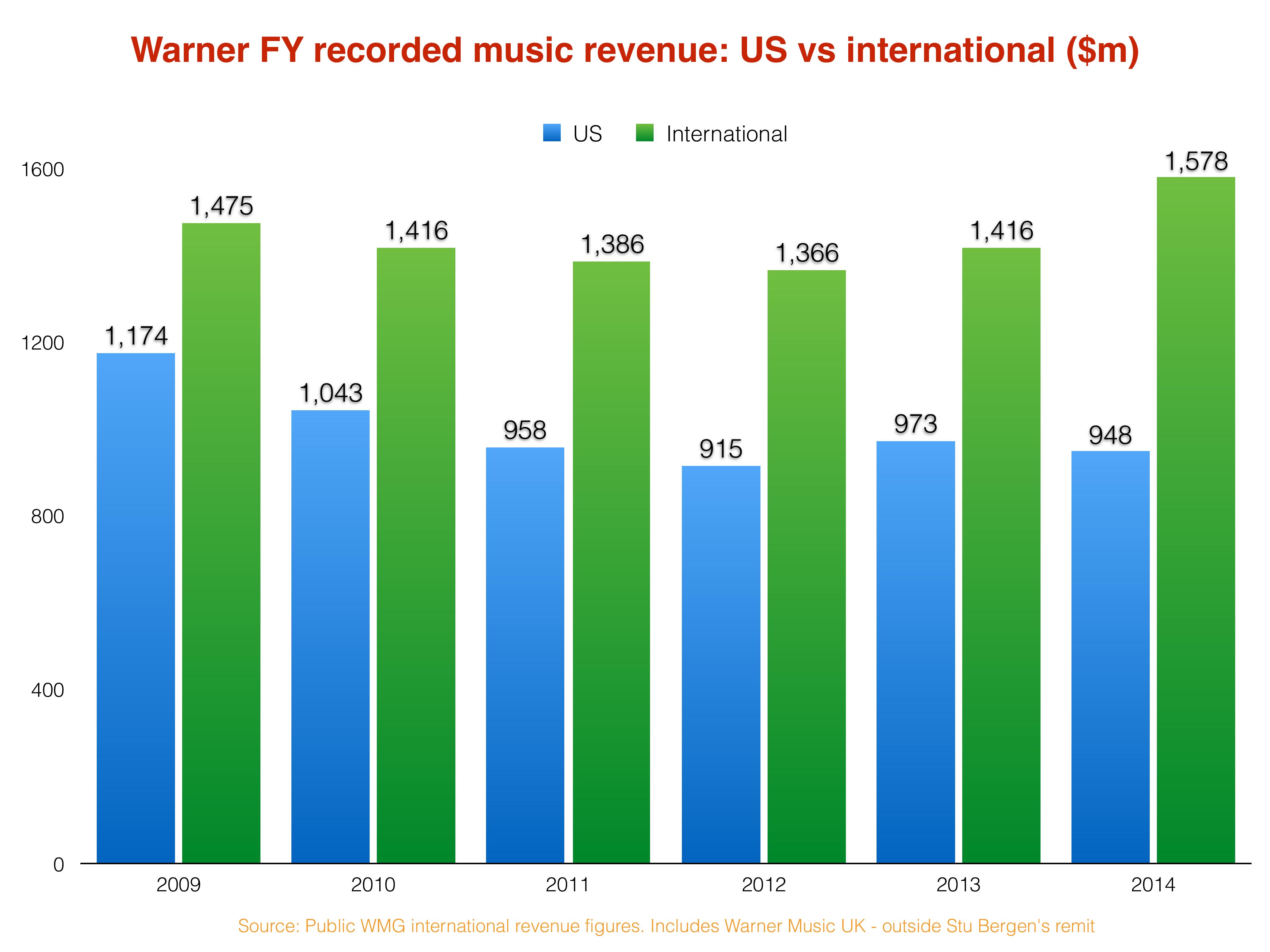

Warner Music Group makes considerably more money outside the US than it does in its home territory.

In 2014, international recorded music revenues at the major topped $1.58bn – a bigger figure than it had accrued in recent memory, and 16% up on its annual ex-US haul just two years prior.

Tellingly, US revenues made up just 37.5% of total 2014 Warner recorded music income, with almost two-thirds coming from elsewhere in the world.

(If you view a lack of reliance on the US market as a strategy-in-progress, Warner’s even further ahead than French-owned UMG, which brought home 39% of its revenue from the US market in 2014.)

These ‘international’ revenue stats, taken from public WMG filings, include Warner Music UK, which sits outside of Bergen’s jurisdiction.

Yet when both the US and UK are removed, MBW is told, Warner’s total revenues were up 11% year-on-year in 2014 – a third year of consecutive growth.

This success has clearly been driven by one defining catalyst: the $3.3bn takeover of Warner Music Group by Len Blavatnik’s Access Industries in 2011.

Since Access’s buyout, Warner has snapped up no less than five international businesses, while pumping money into international A&R resource.

As a result, the major’s ex-UK and US revenues were up by 19% in 2014 compared to the year Blavatnik took over the company.

“BY THE END OF 2011, WARNER’S ATTITUDE HAD SHIFTED FROM A PARADIGM OF CONTRACTION TO ONE OF EXPANSION.”

STU BERGEN, WMG

“The Access acquisition was a total paradigm shift for Warner Music,” says Bergen.

“For many years in this industry, there was an impression that the international countries mainly existed to sell hits from the US and UK. This became more pronounced when digital piracy hit, making people and money more scarce.

“But by the end of 2011, we had new ownership, new management and we took a new approach to our international business. Our attitude shifted from a paradigm of contraction to one of expansion.

“Access is a truly global company that sees opportunity far beyond the UK or US. With Steve Cooper as CEO, we’ve been empowered to invest much more aggressively in building the strength of our local operations.

“And that’s fed our ability to break global stars.”

The evidence of this expansion has been highly apparent in the past two years.

Take Brazil, for example, where Warner re-entered domestic A&R in 2013, and has since broken a duo of big new stars, Anitta and Ludmilla – while increasing market share by 40%.

Over in Russia, Warner swooped for the market’s biggest independent music company, Gala Records in mid-2013.

Later that year, it bought out Gallo Records in South Africa, a move that has allowed WMG to completely manage the release of its own repertoire across Africa.

Last year was largely all about China.

“WE CAN BE STUBBORN IF WE THINK THE BUSINESS IS HEADED IN THE WRONG DIRECTION.”

STU BERGEN, WMG

First WMG acquired Gold Typhoon, which owns one of the biggest collections of local pop and rock music from China, Hong Kong and Taiwan in existence.

Warner then struck a pioneering deal with Tencent – the first-ever master distribution partnership between a major record company and a leading ISP in Mainland China.

Interestingly, the likes of Sony Music and BMG have followed with their own exclusive digital distribution partnerships in China.

(China promises to be one of the good news stories of 2015 for the music industry: in July, China’s National Copyright Administration announced that more than two million songs had been deleted from local torrent sites as part of a widespread government crackdown on web piracy.)

“We’ve significantly bet on China as an opportunity and now it’s started to come through,” Bergen tells MBW.

“A lot of work still needs to be done, but we’re on our way to a rational market. A population of 1.3 billion people is always going to be hugely promising.

“The notion of licensing our repertoire to an internet platform like Tencent was initially a little strange. But our team there were amazing: they saw the opportunity and grasped it.”

“I’ve been very impressed with Tencent’s desire to turn China into a long-term rational market and fight piracy,” he adds.

“We were the first to do it, and we pride ourselves on the fact that if a decision makes sense, we’re not afraid to be pioneers. We can be stubborn if we think the business is headed in the wrong direction.

“We don’t have to wait for others to do what we think is right.”

There have been other multi-million dollar international acquisitions at Warner since Blavatnik’s arrival, including Poland’s oldest record label, Polskie Nagrania, earlier this year.

Yet one name on this inventory has attracted more industry discussion, and MBW column inches, than any other: Parlophone Label Group.

The £487m ($765m) paid by WMG for Parlophone was a princely sum, but there’s no doubting the quality of the catalogue it afforded Warner – from David Bowie to Blur, Pink Floyd, Kate Bush, David Guetta, Radiohead and Coldplay.

(Warner still owes the independent sector over £100m in divested assets as a result of this purchase. Held up due to over-subscription and legal complexities, it was a deal that was initially announced more than 1,000 days ago.)

“There’s no doubt in my mind that the PLG acquisition was a turning point for WMG,” says Bergen.

“It not only bolstered our girth, it sent a profound signal to the business at large, and our artists, that we we’d flipped the switch to this strategy of expansion.

“[BUYING PARLOPHONE] HAS MADE US MUCH STRONGER IN EUROPE, AND CHANGED OUR MENTALITY.”

STU BERGEN, WMG

“It’s made us much stronger in Europe, and it also changed our mentality. We are a much stronger company today than we were prior to doing the deal.”

He adds: “We’re now viewing every one of our operations as creative and commercial engines in their own right. It’s about every country being both an exporter and importer of success.

“By success I mean hit artists and hit music, but I also mean creative marketing campaigns, new business models, and transformational executives.

“During a period of modest decline for the industry, we’ve significantly grown our revenues in the international territories.

“Our A&R in a nutshell: when we recently had every album in the Swedish top ten, the records came from six different repertoire sources.”

Bergen’s excitement over the challenge of breaking artists from once-unfancied territories around the world is palpable.

He raves about the global potential of Pablo Alboran, who joined WMG as part of the Parlophone acquisition and has been the biggest-selling artist in Spain for the past four years.

Bergen’s team is making a good fist of breaking Alboran globally with his upcoming first English language album.

WMG’s international network has pulled some serious A&R strings to give it a good shot: MBW is told that two multi-platinum Ango-American stars will both appear on the LP.

“He’s a phenomenal talent and works super hard and we’ll back him all the way.”

Other international stars on the cusp of something big outside their home territories include Danish star Christopher, who’s already scored five Top 10 singles in his local market – where 15% of the population follow him on social media.

Warner is currently rolling out Christopher’s own perfume (pictured right) in Demark’s largest department store chain.

“Now he has to go out there and compete with the world’s best in his field – the Biebers, the Timberlakes – but I completely believe he can,” says Bergen.

Another Nordic superstar on Warner’s books is Lukas Graham, whose story typifies what Bergen sees as a revitalised global opportunity for artists brought about by streaming.

“Countries with high stream counts have a new ability to push their hits onto the global stage,” he explains.

“Lukas Graham reached 53 on the Global Spotify chart when he was only available on an indie label in the Nordics, which shows you the power of the Nordic market to fuel a hit record.

“WBR have signed Lukas for the rest of the world, and the song has jumped to 28. To slingshot artists like him onto the world stage out of countries like the Nordics is breaking down the traditional stranglehold of US/UK.

“Once upon a time you could ignore it: ‘Ah, it’s just big in Sweden.’ Now these global platforms push it out there for all to see.”

It’s a similar story with Warner-signed Robin Schulz – the German DJ who’s notched up multiple No.1 singles in the likes of the UK, France, Italy and Sweden, and gone Top 20 on the Billboard Hot 100.

Says Bergen: “Think about it – what was the last big hit out of Germany? Falco? Nena? Those are going back to my childhood. Today more than ever, hits can come from anywhere and translate everywhere.

“At the same time, a number of US and UK signed artists have had their first hits in other countries, like Galantis in Holland, Jamie Lawson in Australia and Kwabs in Germany.”

Warner wouldn’t have been able to fuel these international careers, of course, without that all-important “paradigm shift… from contraction to expansion”.

Talk of Len ‘Richest Man In Britain’ Blavatnik’s fear-averse impact on the major music company begs a rarely-discussed question.

Other than trading its debt publicly, Warner is essentially owned by a single billionaire’s vehicle.

It is arguably, to all intents and purposes, an independent organisation.

Bergen is clearly proud and excited by the autonomy and flat structure of Warner. But does he think the company is a major or an indie?

“We could be both. We might be neither. We go our own way,” he replies. “There’s a soulfulness to how we approach artists but also an aggressiveness about our expansion around the world.”

“WE’RE OWNED BY THE ONLY GUY WHO CAN’T BE FIRED AT A MAJOR MUSIC COMPANY.”

STU BERGEN, WMG

He adds: “We’re a company that does one thing: music. We’re not part of a bigger business that does a bunch of stuff. That singularity of vision is helpful to our mission and appealing to artists.

“Our ownership structure gives us incredible flexibility to move quickly. We can make major decisions very efficiently because their is not a big bureaucracy to wade through.

“We’re owned by the only guy who can’t be fired at a major music company.

“That’s empowering, it breeds confidence, and it’s definitely something we leverage to our advantage.”