Hank Shocklee, producer

During the disco boom, the money was flowing so crazy that even the messengers were riding in limos – and then the business crashed. Bands couldn’t afford a drummer or a bass player and that’s how rap was born: we’d build tracks from samples of records. But even when we were bigger than R&B and rock groups, we could barely get our videos shown – just once a week, on Yo! MTV Raps. Rap was a dirty word. Radio stations didn’t want to play it, the Grammys didn’t even acknowledge it.

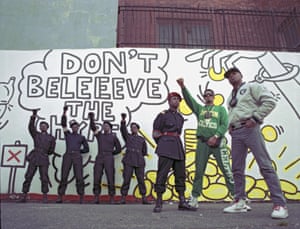

It was a time of huge racial tension, too. Hip-hop culture was just starting and no one understood it. Kids would be out on the streets chilling, shoelaces untied, hats on backwards, and they’d be getting harassed by police. The economy was fucked up and crack was hitting the black community hard. Everyone had a friend or relative on crack, who was stealing from them. We had our cars broken into so many times, when we were up late in the studio. The hood was on its own, abandoned at every level – government, county, city. We had to overcome everything. Fight the Power was going to be the anthem of the streets.

We made the track for Spike Lee’s 1989 film Do The Right Thing. Spike originally proposed a rap version of a negro spiritual, Lift Every Voice and Sing, to be produced by someone else and with just Chuck D rapping. I was like: “No way.” We were in Spike’s office on DeKalb Avenue in Brooklyn, by a busy intersection. I pulled down his window, stuck his head out, and was like: “Yo man, you’ve got to think about this record as being something played out of these cars going by.”

So I worked on reinterpreting what Spike meant. My brother Keith had this drum beat with a couple of percussion loops. It had an energy, an urgency, but not to make you mad. It felt uplifting. But how do you evolve that into a song using only samples? The track had to have a sense of camaraderie,whilealso being a call to arms – and it had to come from a Public Enemy perspective. The whole PE culture was about disruption. That’s where the guitars come in. I wanted a Deep Purple kind of energy, but with melody. Rock’n’roll guitar wouldn’t work, too much edge. This needed to be softer, though still with the bite of angst.

The drums had to feel like African war drums, but instead of us going to war, it had to be like we were already winning the war. It needed less sustain on the bottom end, because too much would put it into a different space: a mad mood. This needed to say: “I’m angry, but I’m not mad to the point where I want to destroy everybody. Instead I’m charged with the energy of overcoming something.”

Me and Chuck then built up the track. It was a totally different process from today, when cats listen to a finished track then put rhymes on top – that separates emotion and content. All the samples have to work with Chuck’s emotion. We’d have to find something from all our hundreds of records to fill a second, and it all had to be done by ear, without computers or visual aids.

It’s easy to make a dope beat, where the kick and snare are keeping the groove together. But Fight the Power doesn’t have that. You can’t tell what the kick and snare are doing. They’re creating a backdrop, but it’s not pronounced, it doesn’t swing. It’s more of a head-bob, reminiscent of a Black Panther rally, a put-your-fist-up kind of vibration. If a song has swing, if it makes you move from side to side, that’s a different emotion, all about celebrating something. That’s what set Fight the Power apart: it wasn’t trying to be groovy. The groove couldn’t be so hypnotic that you’d get lost in it, since then you’d lose what the song was about. It would be a good song, but not an anthem.

The record’s almost like an Easter egg hunt. Kids wouldn’t just listen to the lyrics, they’d try to identify all the little samples in there (such as Funky Drummer by James Brown, Sing a Simple Song by Sly and the Family Stone and I Shot the Sheriff by Bob Marley). It went back to the “digging in the crates” culture. That’s what gave the records their appeal on a street level, a feeling of: “Wow! I didn’t know you could put all that in there – and where did it all come from?”

Getting the final mix right was just as important as finding all those other elements. The song could have gone a lot softer, a lot neater, a lot tighter – but it would have lost the chaos. When something is organised and aligned, it represents passivity. But any resistance, any struggle to overcome, is going to be chaotic. So the hardest part was making sure the track wasn’t monotonous. Lots of the samples appear only once, and a lot of stuff isn’t perfectly in time. I didn’t just want white noise and black noise – I wanted pink noise and brown noise!

Chuck D, vocals

I wasn’t the first person to write a song called Fight the Power. The Isley Brothers did that in 1975. They talked about how we needed an answer to government oppression. I just built on that. If the government dictates who you are, then you’re part of the power structure that keeps you down. We were going to fight that and say: “Look at me as a human being.” The government wanted rap to be infantile, to have us talk about cookies and girls and high school shit. I was like: “Nah, we’re going to talk about you.”

We came up with the rhythm, then started adding samples. You might hear a collage of 25 or 30 different sounds and words all at once, blended into a concise line of thought and feeling. We didn’t leave any space empty. Why would you have someone rap over just a bassline? Just as Bo Diddley played the guitar like a drum, we played samples like a drum. We were piecing together a quilt of noise.

Minimalism in rap came later, because people couldn’t afford the samples, and it became the norm. Is it more exciting now? Probably not. Because the sampled musicians were the greatest of all time. If you’re picking something from the 60s and 70s, you’re picking magic. I once told the Rolling Stones: “I’ve stolen everything I can off of you!”

Some of my lyrics were controversial: “Elvis was a hero to most but he never meant shit to me.” I never said Elvis was wack, but it’s a racist notion to say he’s an icon – the King – when rock’n’roll started before him. But my skin has been seen as more hostile than anything I could say. Black people, our skin is noisy.

The record was cool, but it was enhanced by a video, and it also had a major film attached to it. There was a movement behind it too: New York had a lot of issues and needed an anthem. Today you have hit records that need financial help because they have nothing else to hold them up: rap music is dictated by big business. It’s totally lawyer-driven and everyone’s looking for a jackpot. Back then, though, it had a political movement to support it.

But the lives of black Americans haven’t got better since Fight the Power. We’re more disconnected as a people, we’re duped by the government’s illusions. Anything good that comes out of the people is kept from the people. Public Enemy were ignored by American TV and radio right after Fight the Power. We weren’t going to get a fucking TV show, we weren’t going to be NWA. We refused to lose to stereotypes.

Songs are like little earthquakes: after Fight the Power, the fucking world shook, and then it went back to the way it was. Law is the only thing that makes everything change. Revolution alters laws and, yes, a song can spark revolution. But songs now strike individuals one by one: some hear them now, some next week, some never. We’re far removed from the days when everyone heard something at the same time.

Fight the Power connected wherever we went. I remember being told Croats and Serbs were singing it together, back when they were at war. Art liberates human beings, but governments want to keep them apart. When people ask if I’m American, I say no, I’m a fucking Earthling.

[TheGuardian]