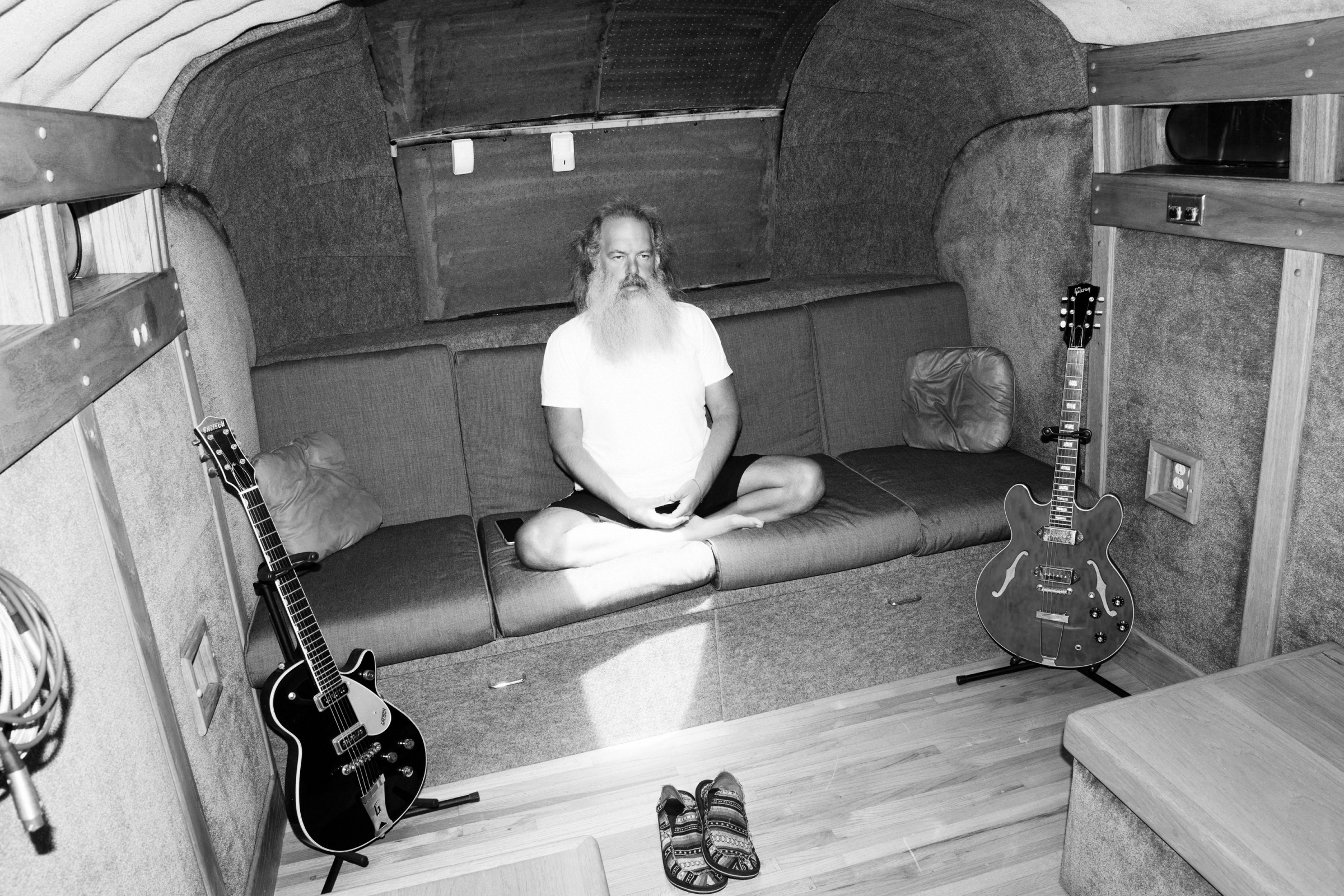

About 15 miles into Malibu’s advertised “27 miles of scenic beauty,” the Pacific Coast Highway bends to the right and delivers you to storied Zuma Beach, a Southern California landmark namechecked in songs by The Rolling Stones and Leon Ware. A little up the hill, overlooking Zuma’s white sand and dazzling blue ocean, is Shangri-La, the musical headquarters of producer Rick Rubin. The studio was originally built in the mid-1970s by The Band and Bob Dylan, and the bus they once used to tour the country is still parked in the grass, its insides turned into an auxiliary recording space. Rubin bought Shangri-La in 2011 and had nearly every surface painted white, save for the pastel pink tile countertops in the kitchen and bathroom.

Shangri-La seems to be a perfect fit for 52-year-old Rubin at this stage of his career. The hirsute, leather-jacketed Long Islander who started Def Jam from his NYU dorm room, brought a traditional pop song structure to hip-hop, and served as a bad influence on the Beastie Boys is now 30 years older. These days, Rubin walks around shoeless in a white T-shirt and black shorts that don’t make it to his knees, his long hair completely bleached out by age and hours spent in the Pacific Ocean. He is tanned and tranquil in his isolation.

Before he settled in Malibu, Rubin had produced music for acts including Slayer, Johnny Cash, Jay Z, Tom Petty, the Dixie Chicks, and Justin Timberlake. More recently, under Rubin’s stewardship, Shangri-La has hosted sessions for superstars like Eminem and Black Sabbath. His work as the executive producer of Kanye West’s Yeezus, where he helped reduce several sprawling hours of material into a minimalist 10-track album under severe time constraints, has brought him a new wave of notoriety. He’s continued to work with developing artists along with legends—recently, he hosted James Blake for the first album the singer will record largely outside of his home studio.

Rubin is a nontraditional producer. He doesn’t play any instruments, and he can’t operate a mixing board or a Pro Tools setup. In fact, he seems to be actively uninterested in spending much time in a recording studio. Instead, Rubin is best known for his talents as a listener, with his ability to offer insightful notes on how artists can improve their songs. He’s a kind of psychological problem-solver, skilled at getting artists to a creative place where they can record and finish the best album they can deliver. Here, Rubin discusses his uncommon approach to his uncommon job.

How do you find new music now?

RICK RUBIN: Usually online. I find myself on SoundCloud a lot. Also, I guess you’d call them trusted sources—friends who have similar tastes who might say, “Have you heard so-and-so?” I wouldn’t say I go out of the way to find it—it’s more like I carry on my natural “interested in things” life and new music finds its way into it. If I made a concerted effort to find new music, it would get in the way of finding the best new music. By not really looking, I feel like I’m finding it for the right reason.

How did you find out about Shangri-La?

I lived very close by and I was making an album with Weezer, and they said, “We found this studio around the corner called Shangri-La, and we rented it for a month and we’re going to rehearse there.” At the time it was not in very good condition. I didn’t know whether the studio sounded good or not. We do these blind tests: I sent an engineer around to all of these different studios—studios that we normally work in and new contenders like Shangri-La—with the same kick and snare drum, the same microphones, and, at the time, a DAT recorder. The instruments and equipment are the exact same in all the tests; the only thing that changes is the room and the air in the room. Then we listen without knowing which is which and decide which studio suits the projects. Shangri-La won one of those projects, and I was shocked because at the time I wouldn’t have guessed anything would have come out sounding good. When it became available and someone was going to buy it and tear it down, I ended up buying it to save it, just because I didn’t want to see it go away.

There’s a reason that some studios survive for forty or fifty years and others are gone in five. In the older days of studio-building, there was a different skill set involved. It was less technical and more artistic. There would be guys with great ears who would know how to tune the room and make it work. Current studios are computer-rendered spaces, which often sound very cold and clinical. They don’t have the same sort of magical sound. A lot of cool stuff was done here in the ’70s: The Band and Eric Clapton and Bob Dylan. Neil Young came to visit maybe three weeks ago, and he said he played “Cortez the Killer” for Bob Dylan for the first time in this room.

Are new artists excited to record there?

Some are. There’s a very calm vibe here. Most artists don’t want to leave, and they find it a conducive place to get work done. When I say calmness, it’s a lack of outside distraction. Without having outside voices or TVs on, it’s like being in a protected womb where you can really be vulnerable—not reacting to something on the outside, but being more you.

Your approach is usually based on everyone taking their time. But working on Yeezus, there was an insane deadline. Was that exciting for you or something you wouldn’t want to deal with again?

It was fun and it gave me insight into the way Kanye works. That’s his method of getting something finished: he likes to try different versions, so there’s always another version to try. If you have a hard deadline, it’s gotta be done, so it motivates him. I tend not to work that way. Now, having experienced it, I feel like I can be of better service to him.

You’re often called in when an artist needs someone to say, “This is how we’re going to get you back to where you can be your best.” Why do artists need that kind of outside help?

There are so many outside distractions, especially if an artist goes from being a kid with no success to all of a sudden having some success. There’s baggage that comes with that, which really gets in the way of the creative process. And there are not many people who can support them through that because most people involved tend to have a shorter-term view that will not be the best for the artist over the long haul. It’s very unusual for someone to have success and then just be able to deal with it. Anything you can do to be more grounded and rooted in yourself is probably a good thing—things like meditation.

Is it possible to work on an album for too long? You’ve said D’Angelo’s Voodoo is one of your favorite albums. Not to diminish Black Messiah—which is great—but I can’t help but wonder how much great material he left behind.

A great piece of work is a chapter or a moment in your life. If you go past that and into the next moment of your life, the music is going to change. There is something about keeping the chapters coming because, if you wait too long, you’re just going to be missing chapters. It’s not that now you’re finally making the great thing that you started eight years before; you’re probably just making the eighth year’s chapter at that point. There is something about keeping some sort of a flow and working as hard as you can to make the best stuff you can, and if the material is not there, go back and write more. There is something about there being another chapter and saying, “This is where I am now. And this is where I am tomorrow. And this is where I am next time.”