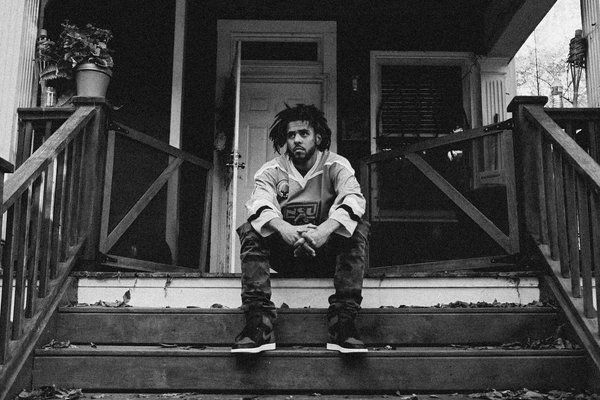

RALEIGH, N.C. — Ask J. Cole about when he realized that the traditional life of a platinum rap star didn’t suit him and he’ll tell the story of the 2013 BET Awards, when a stylist dressed him in a loud Versace sweater that two other people ended up wearing on the red carpet. He’ll talk about meetings with label executives and personal heroes who encouraged him to make musical decisions that, deep down, he never felt comfortable with. He’ll recall an awakening to the potency of the love of the woman he’d been with for years. And he’ll remember his trip in the wake of the killing of Michael Brown to Ferguson, Mo., where the most valuable thing he found he could do was just to listen.

And so, a couple of years ago, after he’d released two platinum albums, he began to make changes. A move back down to this part of the country, not far from where he grew up, in Fayetteville. Meditation every day, or as often as he could manage. Marriage. A commitment to asking about the needs of others rather than only his own. And a decision to make music that spoke to his own creative and emotional idiosyncrasies, no matter how far it strayed from that of his hip-hop superstar generational peers.

He retreated from the spotlight so thoroughly that one recent weekend found him at a Boys & Girls Club here, firing perimeter shots in a playoff game in a local recreational basketball league, largely left to his own devices apart from a handful of picture requests and a couple of mixtapes shoved into the hand of his security guard.

“The other side, it’s what we grow up believing that we need and want. It’s everybody’s dream,” he said, pulling away from the gym in his black Range Rover. “Who doesn’t want the pick of the litter on this, that and the third? Money, women, cars. And beyond all of that — which I really wasn’t into — praise.”

He continued, “It’s addictive. To recognize it, it was the first step.” And to change it required overcoming internal fear: “I had to recognize, well, where’s the fear coming from?”

That internal struggle has led Mr. Cole, 32, a mainstream rap dissident who has gone platinum on each of his albums, to the most fruitful work of his career. In December, he released “4 Your Eyez Only,” his best, most provocative and yet most relaxed album, and on Saturday, HBO will air “J. Cole: 4 Your Eyez Only,” an hourlong special that combines documentary footage of Mr. Cole’s travels to various cities through the Midwest and the South that have personal or political resonance for him with in situ music videos that locate Mr. Cole’s songs as part of a larger conversation about black resilience and dignity under the conditions of white supremacy.

“4 Your Eyez Only” the album is told mostly through a character that’s a composite of two men Mr. Cole grew up with from Fayetteville, and with whom he’s still in touch. He’s a tough guy, a criminal stereotype, except inverted. “The people that I know that live that life and come from that life, or even used to live that life, there’s so much more than that,” Mr. Cole said. “They have multiple sides, and the side that is the strongest is love” — of mothers, of friends, of girlfriends, of children. The album ends in a heart-rending nine-minute apologia written from the character to his daughter, offering explanations for his bad choices and asking for forgiveness. The album’s goal, Mr. Cole said, was “to humanize the people that have been villainized in the media.”

By this point in the conversation, he’d settled into the basement of the Sheltuh, the home in a far-out suburb he and his associates have rented for the last couple of years that has served as a hang spot and the de facto center of operations for his label, Dreamville. On one wall were record shelves teeming with alphabetized 12” singles from hip-hop’s golden age. He bought the collection, a kind of spiritual decoration, from Nervous Reck of Bomm Sheltuh, one of his teenage hip-hop idols.

These are the records, and the era — the 1990s — that Mr. Cole harks back to, and a sound that is a far cry from where the genre has moved in recent years. Still, his commitment has been undimmed. “I understand that what I’m doing is what I don’t see, is what I would like to see being done but is not being done,” he said.

Even though he found conventional success early in his career, he found the life he’d willed himself into to be ungratifying. “Any reasonable person would be ecstatic,” he said. “I didn’t have that feeling.”

And so began the choices that led to him becoming a conscientious objector to the dictates of rap stardom. Rather then continuing to attempt to analyze what might make a hit, a process Mr. Cole said he found unrewarding — “Trying to prove that I could do something that they don’t think I can, it was a very sad place when I look back” — he began making music at home, on his couch, only coming to the studio for the final stages of recording and polishing.

The decisions that emanated from that friction ended up setting the stage for a striking personal and aesthetic turnabout. He got married, and he and his wife, Melissa, recently had a baby. (He declined to reveal the sex or the name.) He now has control of his master recordings. And on “4 Your Eyez Only,” he digs in to deeply emotional narratives, and continues his penchant for tackling left-field subject matter, like “Foldin Clothes,” about the thrills of domesticity. “It’s a celebration of growing up,” he said. “I chose this path, and damn it feels good,” comparing its energy to how other rappers might celebrate a new Bentley.

It also transformed him from a student of the great storytelling rappers to a teacher. That’s clearest on “False Prophets,” released separately just before the album (it wasn’t included because it disrupted the narrative), which found Mr. Cole diagnosing the neuroses of his peers and heroes without naming them, though the internet filled in the blanks quickly.

Rappers rap about other rappers all the time — subliminal insult, direct attack — but rarely from a place of love. “That speaks to the state of us as a people,” he said. “For so long my mind state was, I have to show how much better than the next man I am through these bars. Who’s the best? Let me prove it. And it’s just like, damn, I’m really feeding into a cycle of keeping black people down, I’m really feeding into that.”

Mr. Cole knows that the disease of stardom inspires cries for help, and now, instead of judging from afar, he wonders, “There’s nobody around you to listen? There’s nobody listening?”

Listening is his new métier. The way Mr. Cole presents in his HBO special, which he directed with Scott Lazer, is primarily as observer, not actor. He returns to Jonesboro, Ark., where his father is from, and the two men visit a community center that serves as a makeshift museum of local black history. In another scene, in Ferguson, Mr. Cole watches as two men argue about government obstacles to black progress. Throughout the show, apart from when he’s rapping, Mr. Cole’s voice is barely heard, but his eyes are taking it all in.

“I felt like it would be mad powerful for black people to see black people talking to each other. And you see a rapper who’s considered one of the biggest in the game, just listening.”

“I felt like it would be mad powerful for black people to see black people talking to each other. And you see a rapper who’s considered one of the biggest in the game, just listening.”

He added, “These are people that never get to be heard, by the world or even by each other.”

That lack of representation, Mr. Cole said, can lead to potentially catastrophic misunderstandings. In March of last year, police raided the Sheltuh; Mr. Cole believes a neighbor was fearful it was a drug den. Security footage that captures the raid is used in the HBO special, showing dozens of heavily armed men forcibly entering the building only to find, well, nothing. (A ticket was issued for a small amount of marijuana found on the premises, he said.)

“I wrote six songs that weekend,” Mr. Cole noted wryly — they included the powerful “Neighbors,” from the new album.

After speaking for a couple of hours, Mr. Cole wandered back upstairs and chatted with a friend who’d recently spoken to a friendly neighbor, who took pains to note that she was not the one who had called the authorities. Mr. Cole, who prefers privacy, was frustrated that the locals had caught on to his presence. But he also saw it as an opportunity.

The HBO special was around the corner, and if his neighbors were inspired to watch it, “they’re going to listen to black people for a hour,” he said. “See how human they are, and see black men walk around with their daughters, and get a whole different perspective.”

“If I’m listening,” he said, “why can’t you listen?”

This article can be found on NYTIMES.COM