PARIS — The electronic beeps and squawks of “Tetris,” “Donkey Kong” and other generation-shaping games that you may never have thought of as musical are increasingly likely to be playing at a philharmonic concert hall near you.

From the “ping … ping” of Atari’s 1972 ground-breaking paddle game “Pong,” the sounds, infectious ditties and, with time, fully formed orchestral scores that are an essential part of the sensory thrill for gamers have formed a musical universe. With its own culture, subcultures and fans, game music now thrives alone, free from the consoles from which it came.

When audiences pack the Philharmonie de Paris’ concert halls this weekend to soak in the sounds of a chamber orchestra and the London Symphony Orchestra performing game music and an homage to one of the industry’s stars, “Final Fantasy” Japanese composer Nobuo Uematsu, they will have no buttons to play with, no characters to control.

They’re coming for the music and the nostalgia it triggers: of fun-filled hours spent on sofas with a Game Boy, Sonic the Hedgehog and the evergreen Mario.

“When you’re playing a game you are living that music every day and it just gets into your DNA,” says Eimear Noone, the conductor of Friday’s opening two-hour show of 17 titles, including “Zelda,” “Tomb Raider,” “Medal of Honor” and other favorites from the 1980s onward.

“When people hear those themes they are right back there. And people get really emotional about it. I mean REALLY emotional. It’s incredible.”

Dating the birth of game music depends on how one defines music. Game music scholars – yes, they exist – point to key milestones on the path to the surround-sound extravaganzas of games today.

The heartbeat-like bass thump of Taito’s “Space Invaders” in 1978, which got ever faster as the aliens descended, caused sweaty palms and was habit-forming.

Namco’s “Pac-Man,” two years later, whetted appetites with an opening musical chirp. For fun, check out the 2013 remix by Dweezil Zappa, son of Frank, and game music composer Tommy Tallarico. Their take on the tune speaks to the subculture of remixing game music, with thousands of redos uploaded by fans to sites like ocremix.org – dedicated, it says, “to the appreciation and promotion of video game music as an art form.”

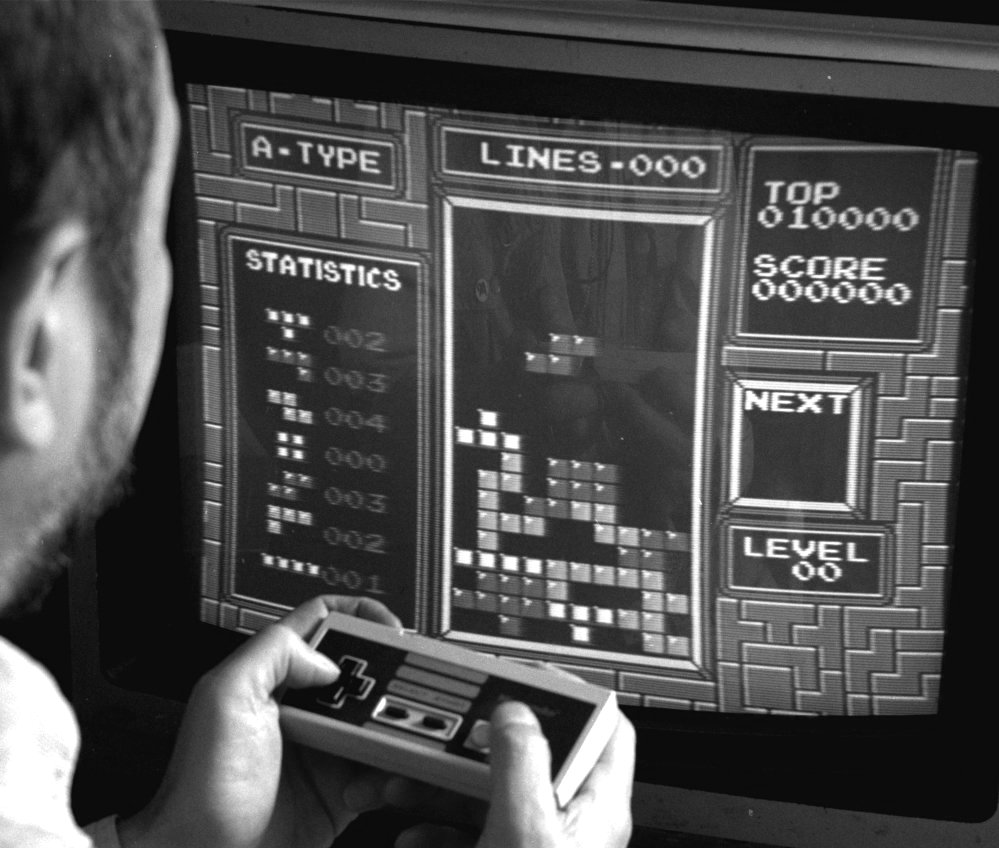

Based on the Russian folk song “Korobeiniki,” the music of the 1984 game “Tetris” has similarly undergone umpteen remixes – including “Tetris Meets Metal,” with more than 2.2 million views on YouTube.

By 1985, the can’t-not-tap-along-to-this theme of “Super Mario Bros.,” the classic adventure of plumber Mario and his brother Luigi, was bringing fame for composer Koji Kondo, also known for his work on “Legend of Zelda.” Both are on the bill for the “Retrogaming” concert in Paris. Kondo was the first person Nintendo hired specifically to compose music for its games, according to the 2013 book “Music and Game.”

Noone, known herself for musical work on “World of Warcraft,” “Overwatch” and other games, says the technological limitations of early consoles – tiny memories, rudimentary chips, crude sounds – forced composers “to distill their melodies down to the absolute kernels of what melodic content can be, because they had to program it note by note.”

But simple often also means memorable. “That is part of the reason why this music has a place in people’s hearts and has survived,” Noone says of game tunes. “It speaks to people.”

She says game music is where movie music was 15 years ago: well on its way to being completely accepted.

“I predict that in 15 years’ time it will be a main staple of the orchestral season,” she says. “This is crazy to think of: Today, more young people are listening to orchestral music through the medium of their video game consoles than have ever listened to orchestral music.”

This year marks the 30th anniversary of the first game-music concert: The Tokyo Strings Ensemble performed “Dragon Quest” at Tokyo’s Suntory Hall in August 1987. Now there are six touring shows of symphonic game music, Noone says.

“This is just the best way, the most fun way to introduce kids to the instruments of the orchestra,” she adds. “It may be the first time ever they are that close to a cellist, and that’s really exciting for me.”

This article can be found on PRESSHERALD.COM