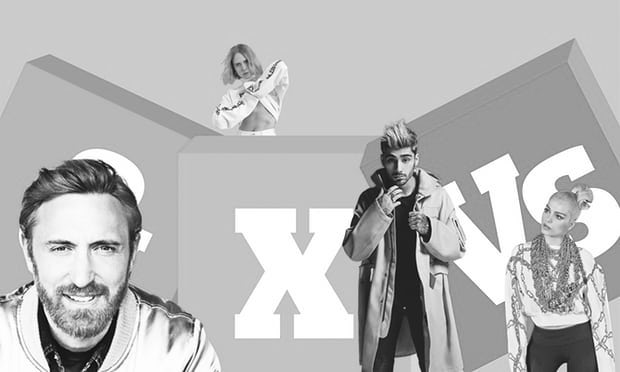

David Guetta is a confusing man for a number of reasons, the latest being his involvement in the aptly titled single Complicated. Sonically, it’s a straightforward approximation of the current pop sound – the song’s true complexity lies in how it’s billed. Brace yourself for an explosion of pop-lexicographical wizardry that will leave you wondering if you’re reading about a pop record or an attempt by the exam board to make equations relevant for A-level maths students: Complicated was released by Dimitri Vegas & Like Mike vs David Guetta feat Kiiara.

Scan the charts and release schedules and you’ll see numerous variations on the theme, from “and” and “with” to “x”, “+” and “presents”. But they don’t all mean the same thing, and there can be fierce behind-the-scenes struggles over how artists are billed, how far up the credit chain they’re allowed, or whether they’re even credited at all. So just how important is a credit on a hit song? Let’s kick things off with British singer Kyla. She scraped the Top 50 in 2008 as the voice of UK funky track Do You Mind, but by last year she was resigned to the idea that music would only ever be a hobby. Then Drake, out of nowhere, decided to sample Do You Mind on One Dance.

“I kept getting all these emails from Sony saying, ‘Contact us, it’s urgent,’” she recalls. “I didn’t think it could be anything that urgent, so I went shopping.” When Kyla got home she called Sony and found out what Drake had in mind, and as well as using the sample he also chose to give Kyla an artist credit, a twist of fate – or twist of feat, if you will – that she didn’t allow herself to believe until the song dropped, just three days after she’d found out it even existed.

It speaks volumes that, when we speak today, this singer who’d all but given up on pop has just cleared airport security on her way to Jamaica to shoot the video for her new single (which will come with its own “feat Popcaan” credit). “Drakecould have just paid me a sampling fee,” she says, “and I probably would have been happy, to be honest. He didn’t have to give me a credit. He could have just said, ‘I want the parts, here’s the money, go away.’ But One Dance catapulted me into the limelight and got people interested again. My life changed overnight. Well, over the space of three nights.”

For context, UK chart historian and Chart Watch UK writer James Masterton says that the importance of a feature credit is as old as pop itself. “The ‘featuring’ tag has evolved in function over the years,” he notes. “In the 50s it was a below-the-line star credit to flag up an important contributor to a record.” By the 80s, “featuring” was used to emphasise the key performer in a larger ensemble, twisting again with the house explosion bringing rise to the idea of producer as performer. Masterton adds that “vs”, for instance, was initially a way to signify two acts “battling” on a record – the first hit example being 808 State vs MC Tunes– but was later mostly used on remixes. Masterton says U2’s manager was particularly good at securing a “vs U2” credit for samples on dance tracks, and the bootleg and mashup scene of the early 2000s gave “vs” yet another lease of life.

“The landscape changed when iTunes came to the fore, and it’s changed again with streaming,” says Positiva/Virgin A&R director Jason Ellis, who’s worked with acts like David Guetta, Gorgon City and Duke Dumont. “iTunes wouldn’t support ‘vs’, so we couldn’t use that any more.”

Last year, Zedd shifted from simply featuring an artist (as on Grammy-winning Clarity, released as Zedd feat Foxes) to a more chummy approach – his last few releases with vocalists Alessia Cara and Liam Payne have all used the suffix “with”. It implies a more organic approach to song creation than “feat”, which suggests two artists that have never met, but Zedd’s manager Dave Rene gives a more logical explanation. “Spiritually and creatively there are a lot of different drivers we think about with respect to ‘with’ and ‘featuring’ and all the rest,” he begins. “But at the end of the day, a lot is determined by DSP partners.”

Those digital service providers – Spotify, Apple Music et al – each display artist credits slightly differently, and metadata submitted to the pop machine needs to cover all bases, but the key phrase here, Rene says, is “primary artist”. “With the Alessia Cara track we used ‘with’ because if you have someone simply featured, they’re not considered a primary artist. We wanted Alessia to be a primary artist – that way, on her profile page the song is seen as her latest release, as well as Zedd’s. If she was just featured, or a secondary artist, you’d miss a lot of potential streams.”

Algorithm-related techniques aside, there’s still nuance to each type of billing. At Columbia Records, A&R Julian Palmer suggests that “with a rap feature, if they’re coming in and doing eight or 16 bars, does that really justify an ‘and’? I’d say no – that is a feature, not a collaborative credit.” One of Palmer’s artists is Snakehips, who’ve released singles with credits ranging from “& MØ” to “feat Zayn”. “With MØ,” says Palmer, “she was incredibly involved in the early stages, so that ‘&’ made a lot of sense. And as for the Zayn thing, that came slightly before everyone twigged that ‘and’ would benefit us on Spotify.”

He says it’s rare for a featured artist to kick up a fuss over what sort of credit they’ll get, but there can be instances where he’ll try to block someone getting more credit than they deserve. “We could bat it away if it’s a brand new artist,” he explains. “So it would be ‘featuring’, or, in some cases, the artist might not appear at all – they might just get ‘vocal by’ in the label credits.”

Good luck tracking down label credits on that new Spotify release. But uncredited vocalists do still occur – fair enough with Galantis, who manipulate vocalists such as Cathy Dennis and Dragonette beyond recognition. Less in the case of Avicii, whose first huge hits, like Wake Me Up, totally ignored the contribution of a singer such as Aloe Blacc. (Jason Ellis, who worked on that release, notes that Avicii’s manager was adamant that no featured artists would be credited – a stance that’s been reversed on Avicii’s current EP.)

“When you’re really attached to something, you want to get the credit for what you think you’ve done,” reasons producer Nick Gale, AKA Digital Farm Animals, who admits he wouldn’t have minded a credit on one Galantis song he contributed to. “The problem is that everyone always thinks they’ve done everything.”

One recent Digital Farm Animals release, Millionaire, came out as Digital Farm Animals with Cash Cash featuring Nelly, but only in the UK. “I wrote the chords and hook, then Cash Cash got involved and really liked it, so we worked on it together,” says Gale. “They wanted it as their single, but I wanted it as mine. We decided the fairest way would be for their name to go first in the US, and mine would go first in the UK. It’s all really petty, isn’t it? I wonder if people really care.”

Listeners may not always consciously think about the hierarchy of artist credits but most of us tend to assume that names will be listed in order of importance, so it’s also reasonable that artists should want their names to come first. Or, indeed, at all. In 2015, US singer songwriter Bebe Rexha wrote and performed the chorus on Hey Mama, a track that was released by “David Guetta feat Nicki Minaj and Afrojack”.

Understandably, she didn’t find it pleasant hearing “the new song from David Guetta and Nicki Minaj” on the radio, with listeners being left to assume that her vocals were performed by Nicki. “It was gutting,” she recalls. “It feels like someone’s punched you in the stomach. It was my first big voice on a big hook with two big superstars, and it was hard. Really hard.”

Rexha says that when she first asked David Guetta about a featured artist credit “he said it wasn’t going to happen”. “I didn’t want to ruin my relationship with him,” she says now. “I was just scared, you know? I didn’t want anybody to hate me, I felt new and I had a lot to prove.” Ultimately there was a happy ending – Bebe’s name was finally added – but it can’t be overstated how much power there is in getting credit where it’s due.

At the time of writing, 24 songs in the Top 40 are joint efforts, and with collaboration culture showing no sign of losing pace, it’s Kyla who offers the best advice for any artist finding themselves on another artist’s song: fight for your feat. “The credit is the key,” she insists. “With One Dance, the money’s been amazing and all the added bonuses have been great, but being given the feature credit is the best part of it all. It’s like I won the lottery.”

Originally posted on THE GUARDIAN