“A mechanical tool is following an intricate signal.”

“These are coaxial speakers, and the tweeter’s in the throat of the woofer.”

“Now you have 16 sets of stampers for a set of lacquers.”

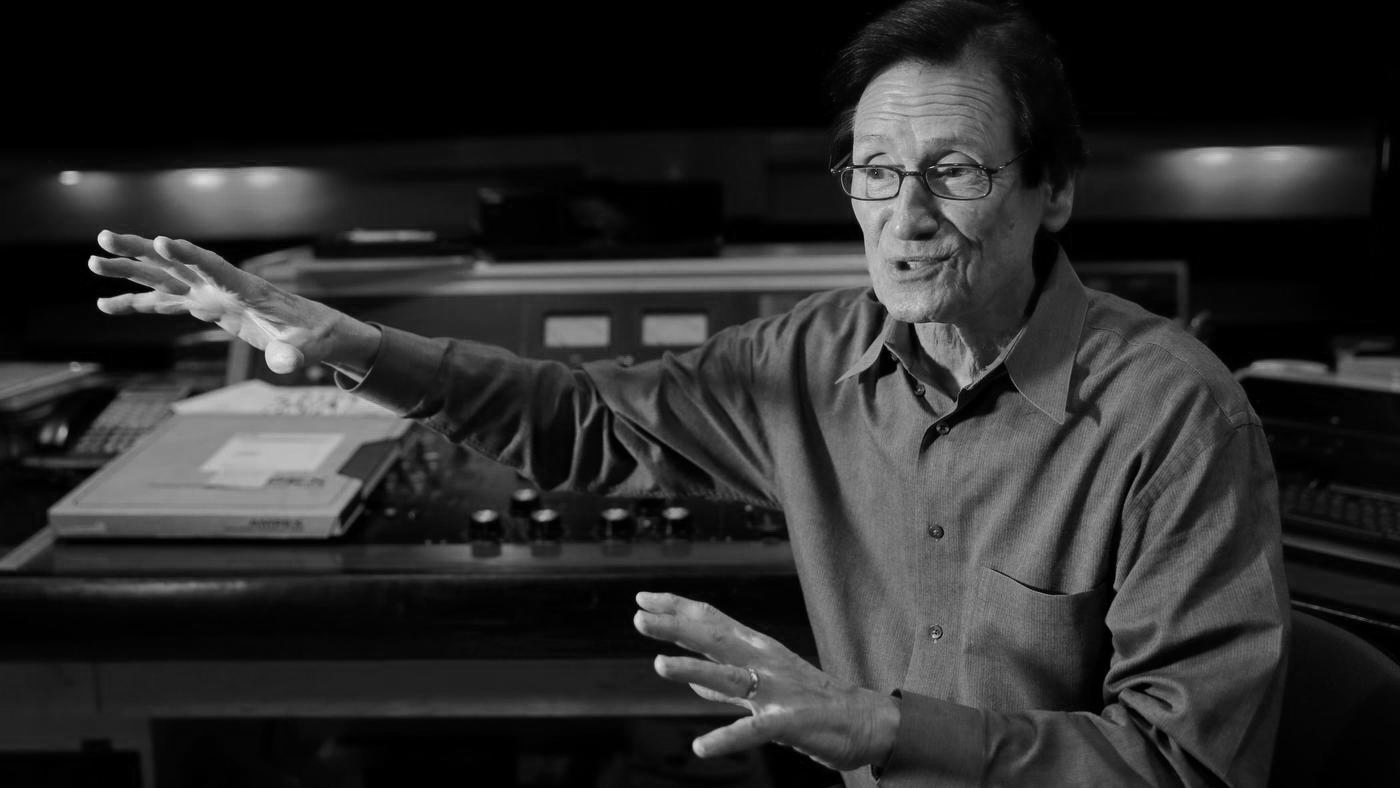

The language can get pretty heady when Bernie Grundman is talking shop at his sprawling, 20,000-square-foot studio in the heart of Hollywood.

One of the music industry’s most respected mastering engineers, Grundman specializes in an arcane yet crucial part of the recording process — the last step, essentially, before a piece of music is readied for mass consumption on CD or vinyl or, as is most often the case these days, as a stream of digital information beamed down from the cloud via Spotify or Apple Music.

Mastering involves striking the final balance of the various elements in a mix, getting the dynamics just right, controlling the amount of silence between tracks — each of which can significantly affect an intricate production like some of those Grundman has mastered, including Michael Jackson’s “Thriller” and Steely Dan’s “Aja.”

Yet for all his facility with the nuts and bolts of audio technology, Grundman, 73, insists that what he really deals in — the reason A-list producers and pop stars have been coming to him for decades — is feeling.

“Our object here is to make sure that these recordings connect emotionally with the listener,” he said on a recent morning at his studio, where he’s scheduled to present a seminar Monday as part of the month-long Red Bull Music Academy series that has also featured performances by St. Vincent and Ryoji Ikeda. “We want them to feel all the depth and the value of the music, that expression of the human experience.”

Grundman’s studio, which he opened 20 years ago following earlier stints in other buildings around town, reflects that intimate aspiration.

A former Social Security office just a few blocks from such storied Sunset Boulevard recording studios as United and EastWest, the high-ceilinged place houses six separate mastering suites for staff engineers including Mike Bozzi (who mastered Kendrick Lamar’s three studio albums) and Patricia Sullivan (who regularly works with film composers such as Danny Elfman and Hans Zimmer). Each is decorated slightly differently, with specific lighting schemes and wood finishes.

In Grundman’s suite, a row of framed snapshots — there he is with Tom Waits — sits behind a cozy sofa; in each picture, he looks like somebody’s favorite uncle, grinning warmly as though the other person had just caught a 10-pound bass or won first place in a spelling bee.

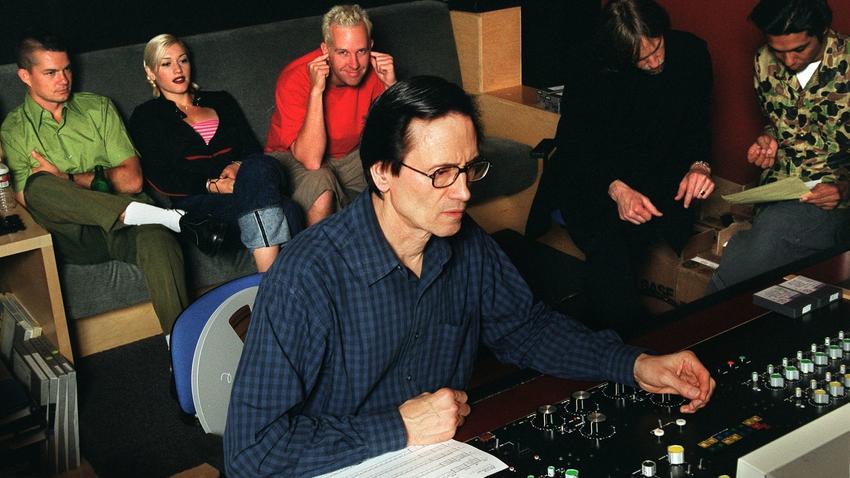

Grundman in his studio with the members of No Doubt in 1999. (Ken Hively / Los Angeles Times)

“I’m one of the old-timers,” he said with a self-effacing chuckle. Grundman was dressed in a button-down shirt and jeans, his hair parted neatly on the side. As he and I spoke, a young assistant placed a demitasse cup before me.

“Now, see, that’s important,” Grundman said. “You’re getting our secret weapon. This comes from Rome; it’s one of the best espressos I’ve ever had. Very smooth.”

I took a sip.

“No bitter aftertaste,” he noted with pride. “You don’t need anything in it.”

The creature comforts may be a natural extension of Grundman’s friendly nature. But they also make good business sense at a moment when his uncommon technical skill — his ability to make a recording sound alive — isn’t quite as valued as it once was.

Not that he’s hurting, exactly. Last year, Grundman mastered the latest album by rapper Childish Gambino (the stage name of actor, writer and director Donald Glover of “Atlanta”), which spun off the Top 40 radio hit “Redbone.”

But in an era when many music fans are abandoning physical formats for lower-quality digital streaming (and listening through crummy earbuds), Grundman’s pricey mastering work strikes some acts and labels as an unnecessary expense.

“Budgets are low,” he said, one result of a dramatic drop in record sales that began around 2000 with the advent of peer-to-peer software like Napster. “And because a lot of records only come out on iTunes or Spotify, these inferior formats, you’re not going to hear the difference” between what Grundman does and what a computer plug-in can do.

“Say what I do for somebody is 30% better,” he continued. “Well, when you put it through the coding device that does the digital compression [for streaming], that 30% is now only 10 or 15.”

In its effort to reduce the size of a digital file, the compression “makes all the instruments sound like each other,” he said. “They start to lose their individual integrity,” which is precisely the thing Grundman says he’s seeking to preserve.

“But some people don’t mind that, because it doesn’t distract them from the other things they’re doing. Now we can work on our computer or look at our phone and not be distracted by the music.” His face flashed a rueful expression.

“It’s kind of sad.”

Grundman shows off his machine for cutting master discs for vinyl production. (Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

Grundman is making up for some of that lost business with a boom in work he once thought was destined to dry up: remastering classic albums for reissue on vinyl.

According to the music tracking firm BuzzAngle, vinyl sales were up 20% in the first half of this year versus 2016, driven in part by a nostalgic impulse among some listeners to hold a record in their hands.

In recent years, Grundman’s operation has handled reissues from U2 and Pink Floyd, and he recently oversaw a new rollout of Buffalo Springfield’s catalog.

During our chat, he led me out of his suite to a cramped space at the rear of the building in which two hulking machines sat — solid aluminum lathes tricked out with computers designed to carefully etch grooves into vinyl discs.

“When we moved in here, we thought discs were half-dead,” Grundman said. “Now this is probably our busiest room.”

Grundman’s goal in mastering vinyl is crafting records that will sound good on a wide range of record players — from the $100 jobs Urban Outfitters sells up to the high-end models that go for thousands.

He’s not dismissive of those cheapo numbers, either. Whatever gets people listening to music more intently — which vinyl requires, he said, because “you have to take the record out of the jacket, put it on the turntable, flip it over to the other side” — is a positive development in his view.

“You hear stories that kids, teenagers and stuff, are actually getting together and listening to records,” he said. “That’s good!”

Grundman certainly listened deeply when he was a kid. Growing up in Phoenix, he had his mind blown by “Study in Brown,” the 1955 album by jazz trumpeter Clifford Brown and drummer Max Roach; around the same time, he started hanging out in the projectionist’s booth at a small theater where his mother worked as the bookkeeper.

His fascination with film and audio equipment eventually led him to cobble together his own primitive sound system with money he earned parking cars. Later, as a 19-year-old, he opened an after-hours jazz club and befriended local musicians whose sets he’d often record.

In 1961, he joined the Air Force and expanded his technical knowledge working on radar-jamming equipment. After four years, he left the service and “drove straight to Hollywood and walked into Capitol Records,” he said, “and asked the head of recording, ‘OK, what do I need to do to be a recording engineer?’”

A few years (and a few jobs) later, he was running the mastering department of A&M Records, which he did for 15 years. Then, in 1984, he opened Bernie Grundman Mastering, working first out of the Ocean Way building on Sunset before moving to the firm’s current spot.

In addition to “Thriller” and “Aja,” Grundman is well known for his work on Prince’s “Purple Rain” and Dr. Dre’s “The Chronic.” When I asked him what he thought attracted hip-hop and R&B heavyweights to him, he said it was probably his sensitivity to rhythm, which he said matters more in that music (and in his beloved jazz) than it does in, say, rock ’n’ roll.

Yet he was quick to add that one key to excellence in mastering is keeping yourself open to all genres — an ethos in sync with the playlist-ruled streaming culture that’s threatening his livelihood.

“You can’t be prejudiced” against a certain style, he said, just before he ducked into a session with Adam Sandler’s producer, Brooks Arthur, who had arrived at Grundman’s studio to prepare vinyl reissues of Sandler’s comedy records.

“We all have the same emotions; it’s just different points of view,” he said. “So when you’re sitting in front of the speakers, with whatever comes in, you have to use yourself emotionally to know if you’re getting anywhere with this stuff.

“If I turn this knob, am I making this a more fulfilling experience than it was before?”

This article can be found on LATIMES.COM