“I’ll teach you how to flow,” Antonio tells Sebastian in The Tempest.

Almost as long as hip-hop has existed, scholars both professional and less so have made efforts to compare its lyrics to the work of Shakespeare. The Folger Shakespeare Library offered a lesson, “M.C. Shakespeare,” that asked students to find comparisons between the rhymes of Bard and Busta, and the British rapper Akala recently gave a TED talk titled “Hip-Hop and Shakespeare?”

The question mark in the title wasn’t strictly necessary; the lines connecting the poet of the 16th and 17th centuries to those of the 20th and 21st are clear. But that doesn’t make the efforts to tease out those lines of connection any less compelling. And now there’s a new entry in that canon—one that comes courtesy of the data scientist Matt Daniels, working with that rich gift, Rap Genius.

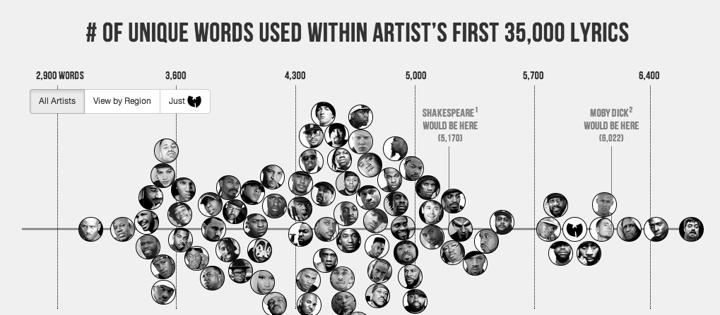

Daniels (you may remember him from such dataviz projects as “Outkast, in graphs and charts“) used Rap Genius data—current as of 2012—to compare the vocabularies of artists like Jay Z, GZA, and Kanye to that of Shakespeare. (He also included Melville’s Moby-Dick in his analysis, but I’ll focus on the Shakespeare comparison here.) The Bard used a total of 28,829 unique words in his work; Daniels set that as his “good vocabulary” benchmark. He then looked at the first 5,000 words of seven classic Shakespeare plays (Hamlet, Romeo and Juliet, Othello, Macbeth, As You Like It, The Winter’s Tale, and Troilus and Cressida), for a total set of 35,000 words. Using token analysis, Daniels determined that Shakespeare used 5,170 unique words in those works.

He then looked at the first 35,000 lyrics of an assortment of hip-hop artists—roughly three to five studio albums’ worth of words. This meant that artists like Kendrick Lamar and Biggie don’t have enough material to be included in the set; it also meant, though, that several emerging rappers are included in the set, and that they’re on equal footing with prolific veterans like Jay Z.

Check out Daniels’ interactive visualization for yourself; it’s fascinating. (He prefers the data to be experienced that way, Daniels says, rather than as a simple ranking, both because he wants “the reader to become entranced in the chart” and also because “it’s really the relative positioning of the rappers that matter, not the raw number.”)

That said, though, one of the most obvious takeaways from Daniels’ comparison is the 15 artists whose vocabularies, according to Daniels’ metrics, rank higher than that of Shakespeare. Another is the vocab-richness of Aesop Rock—whom Daniels had almost excluded from his analysis, on the grounds that he was too obscure.

“Sure enough,” Daniels notes, “Aesop Rock is well-above every artist in my dataset and I was obliged to add him to the chart. In fact, his datapoint is so far to the right that he should be off the chart (I’m lazy and didn’t adjust the scale).”

The set also reveals the diction-richness of the work of the Wu-Tang Clan, which Daniels looks at both as a collective and as individuals: “GZA, Ghostface, Raekwon, and Method Man’s solo works are also in the top 20,” he notes. And GZA as a solo artist ranks second overall, under Aesop Rock.

None of this is to say, of course, that Aesop Rock, or GZA, are better artists than their fellow rappers—or that East Coast is better than West. Vocabulary alone does not artistry make. It is to say, though, that data-driven approaches can shed new light on the connections between the poetry of the past and the poetry of the present. They give us a new way, you could say, to flow.

Originally posted on THEATLANTIC.COM