“For the last three years my hearing has grown steadily weaker…” – so wrote Beethoven, aged 30, in a letter to a friend.

The young Beethoven was known as the most important musician since Mozart. By his mid-20s, he had studied with Haydn and was celebrated as a brilliant, virtuoso pianist.

By the time he turned 30 he had composed a couple of piano concertos, six string quartets, and his first symphony. Everything was looking pretty good for the guy, with the prospect of a long, successful career ahead.

Then, he started to notice a buzzing sound in his ears – and everything was about to change.

Around the age of 26, Beethoven began to hear buzzing and ringing in his ears. In 1800, aged 30, he wrote from Vienna to a childhood friend – by then working as a doctor in Bonn – saying that he had been suffering for some time:

“For the last three years my hearing has grown steadily weaker. I can give you some idea of this peculiar deafness when I must tell you that in the theatre I have to get very close to the orchestra to understand the performers, and that from a distance I do not hear the high notes of the instruments and the singers’ voices… Sometimes too I hardly hear people who speak softly. The sound I can hear it is true, but not the words. And yet if anyone shouts I can’t bear it.”

Beethoven tried to keep news of the problem secret from those closest to him. He feared his career would be ruined if anyone realised.

“For two years I have avoided almost all social gatherings because it is impossible for me to say to people ‘I am deaf’,” he wrote. “If I belonged to any other profession it would be easier, but in my profession it is a frightful state.”

Once Beethoven was out for a country ramble with fellow composer Ferdinand Ries, and while walking they saw a shepherd playing a pipe. Beethoven would have seen from Ries’s face that there was beautiful music playing, but he couldn’t hear it. It’s said that Beethoven was never the same again after this incident, because he had confronted his deafness for the first time.

Beethoven could apparently still hear some speech and music until 1812. But by the age of 44, he was almost totally deaf and unable to hear voices or so many of the sounds of his beloved countryside. It must have been devastating for him.

The exact cause of his hearing loss is unknown. Theories range from syphilis to lead poisoning, typhus, or possibly even his habit of plunging his head into cold water to keep himself awake.

At one point he claimed he had suffered a fit of rage in 1798 when someone interrupted him at work. Having fallen over, he said, he got up to find himself deaf. At other times he blamed it on gastrointestinal problems.

“The cause of this must be the condition of my belly which as you know has always been wretched and has been getting worse,” he wrote, “since I am always troubled with diarrhoea, which causes extraordinary weakness.”

An autopsy carried out after he died found he had a distended inner ear, which developed lesions over time.

Beethoven’s famous Symphony No.5, written in 1804. Its famous opening motif is often referred to as ‘fate knocking at the door’; the cruel hearing loss that he feared would afflict him for the rest of his life.

Taking a lukewarm bath of Danube water seemed to help Beethoven’s stomach ailments, but his deafness became worse. “I am feeling stronger and better, except that my ears sing and buzz constantly, day and night.”

One bizarre remedy was strapping wet bark to his upper arms until it dried out and produced blisters. This didn’t cure the deafness—it only served to keep him away from his piano for two weeks.

After 1822, he gave up seeking treatment for his hearing. He tried a range of hearing aids, such as special hearing trumpets.

Beethoven had heard and played music for the first three decades of his life, so he knew how instruments and voices sounded and how they worked together. His deafness was a slow deterioration, rather than a sudden loss of hearing, so he could always imagine in his mind what his compositions would sound like.

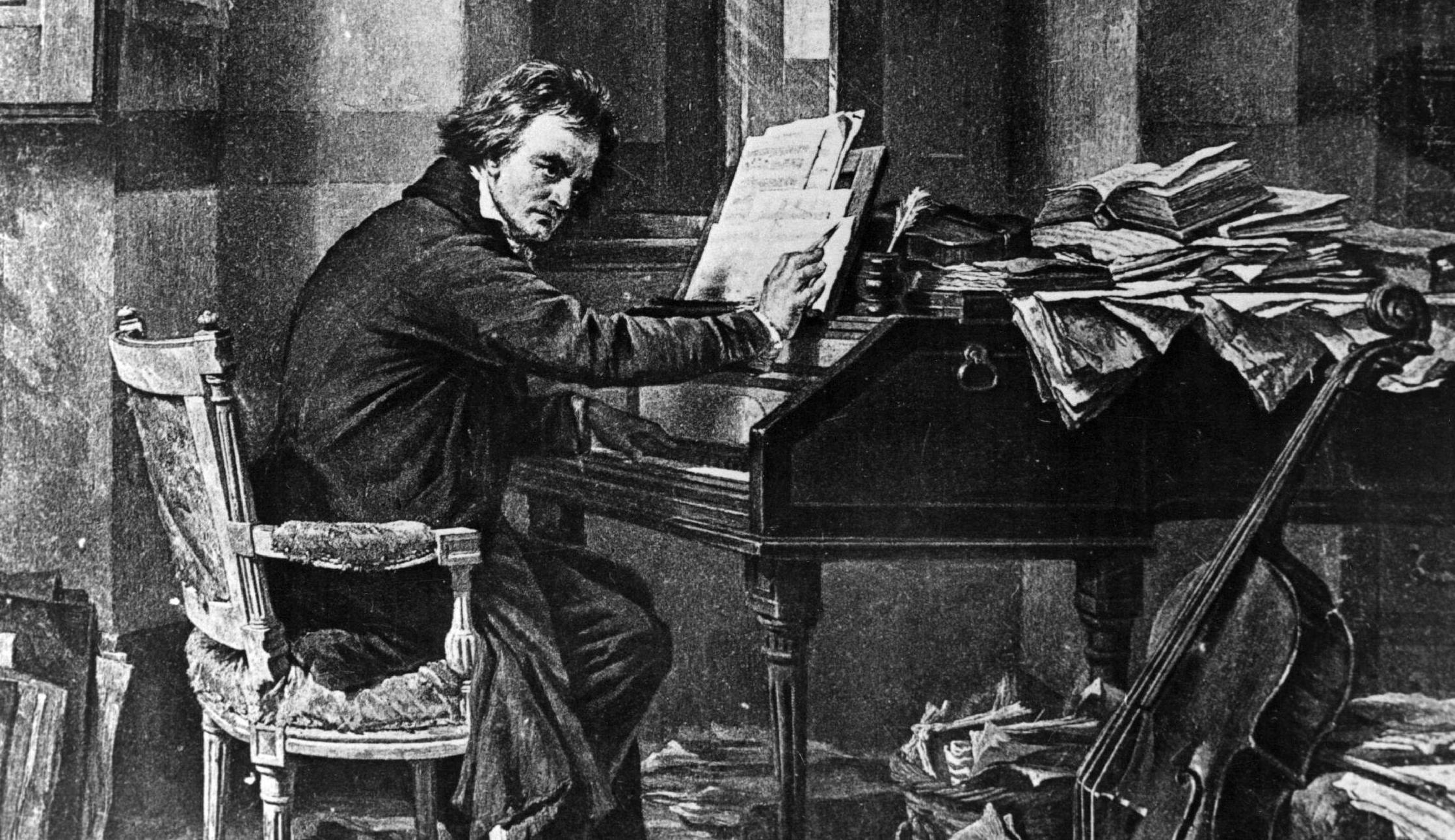

Beethoven’s housekeepers remembered that, as his hearing got worse, he would sit at the piano, put a pencil in his mouth, touching the other end of it to the soundboard of the instrument, to feel the vibration of the note.

In his early works, when Beethoven could hear the full range of frequencies, he made use of higher notes in his compositions. As his hearing failed, he began to use the lower notes that he could hear more clearly. Works including the Moonlight Sonata, his only opera Fidelio and six symphonies were written during this period. The high notes returned to his compositions towards the end of his life which suggests he was hearing the works take shape in his imagination.

After watching Beethoven in a rehearsal in 1814 for the Archduke Trio, the composer Louis Spohr said: “In forte passages the poor deaf man pounded on the keys until the strings jangled, and in piano he played so softly that whole groups of notes were omitted, so that the music was unintelligible unless one could look into the pianoforte part. I was deeply saddened at so hard a fate.”

When it came to the premiere of his massive Ninth Symphony, Beethoven insisted on conducting. The orchestra hired another conductor, Michael Umlauf to stand alongside the composer. Umlauf told the performers to follow him and ignore Beethoven’s directions.

The symphony received rapturous applause which Beethoven could not hear. Legend has it that the young contralto Carolina Unger approached the maestro and turned him around to face the audience, to see the ovation.

Originally posted on CLASSICFM.COM