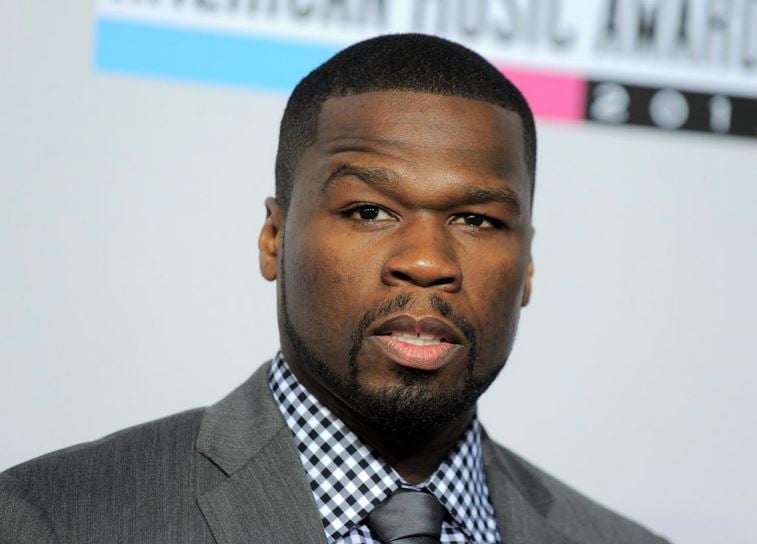

It was announced recently that rapper 50 Cent is leaving his previous record label Shady/Interscope for a new home with Caroline, the label services division of Universal Music Group. The artist and his G-Unit imprint joins a number other artists like Macklemore & Ryan Lewis, Korn, Peter Gabriel, and Prince who chose to leave the comfort of a traditional major label (Shady/Interscope is a subsidiary of the giant Universal Music Group) record deal behind in favor of going independent, but with a new twist. Now the label’s once exclusive services are for hire instead of available only as a byproduct of a traditional recording agreement.

What we may be witnessing is the dawn of a new age in the music business as all the major labels have set up separate divisions to be able to offer their services and expertise on an a la carte basis. Need physical distribution, radio promotion, digital strategy or product development? If you’ve got the money or the audience, you can hire their expertise for these services plus a lot more. Where once upon a time, an artist signed exclusively with a record label for a number of albums, the new label services deals can be for a single album at a time, with none of the traditional multi-record contractual strings attached.

Although some were faster into the space than others, all the majors are now represented. Sony Music has its Red Associated Labels unit, Warner Music Group has Alternative Distribution Alliance (ADA), while Universal Music owns Caroline. In addition, there’s also BMG, which began the trend in 2008 when it sold its traditional record business to Sony to concentrate on artist rights management, as well as the independent Kobalt Label Services and in the UK, Cooking Vinyl.

The reasons why an artist might want to consider such an arrangement are many. First of all, there’s the issue of artistic control. In a traditional record deal, the artist and the record label are in a partnership, with the label as the senior partner. The stories about clashes on creative direction between the artist and label execs are legendary, but all this is alleviated when the artist is independent and hires the label services on a “as needed” basis. The artist is now the boss when it comes to product creation, but the responsibility for making it or breaking it are on his shoulders alone.

Then there’s the payout. A traditional record deal has an artist making between 12 and 15% of the net income, but once again, stories of creative accounting abound, and it wasn’t an uncommon scenario to have an artist sell a million copies back in the days when physical media like vinyl records and CDs ruled only to find that he actually owed the record label money when all was said and done. This is because the label also acted as bank, funding the recordings, tour, and promotion of the product. A label services deal with a company like BMG turns that scenario upside down, with the artist taking 70 to 80 percent of the income for overall rights management, while individual services from other companies may be had for a small percentage of the record or even a fee.

This fits more in line with the do-it-yourself nature of the business today along with the expected payout, since the iTunes 70/30 split has become the expected standard. Any deal that doesn’t talk at least in those terms gets a quick pass when an artist is in control.

That said, artists like Trent Reznor and his Nine Inch Nails have gone the opposite way, going back to the womb of Columbia Records after spending time outside the major label structure as an independent. Some artists, even with the impressive online infrastructure like Reznor had created, still don’t enjoy the burden of dealing with other aspects of the business beyond the creative, regardless of how great the potential monetary split might be in their favor.

While it seems like artists are the big gainers here, labels win too. They can get on with what they’re really good at, which is distribution and promotion, and get paid fairly for those services. They no longer have to worry about being a bank, doling out advances and recording costs, and they can afford to be even more selective in the acts they do sign, which can increase the odds of a hit.

What we’re seeing here is a business model morphing right before our eyes, but right now it’s in its early adoption phase before the ball begins to roll down hill. A more or less traditional recording contract is still the primary ambition of most artists, but that may change before long. For now, it should be a well-considered option for every artist and manager.