After more than a century of cultural flux, music is now priceless. Or is that worthless?

The intricacies of the music industry recently stumped a Nobel Prize-winning economist. The New York Times’ Paul Krugman, sharing a panel with members of Arcade Fire at this year’s South by Southwest music conference, told attendees that successful musicians continue to make most of their money the centuries-old way: live performance. As with the rest of society, though, the lion’s share of that income is increasingly going to only a tiny elite. “I actually don’t quite understand how the bands I like are even surviving,” Krugman said. He was being self-effacing, sure—but probably not entirely.

So: What is music worth? As Krugman’s improbable-enough SXSW presence shows, the question has gained renewed prominence as of late, from celebrity-stirred discussions about online streaming to last month’s $7.4 million “Blurred Lines” jury verdict. The answer, however, is a moving—if not almost invisible—target. Putting the debates about artists’ income from Spotify, Pandora, and their ilk in a broader historical context, it becomes clear that the money made from a song or an album has clearly decreased over the last several decades. What’s equally clear, though, is that the value of music is almost as subjective financially as it is aesthetically; the economics of music, it turns out, is more dark art than dismal science.

No single statistic captures the health of the entire music business. While record sales have plummeted, concert revenues have soared (at least for the industry’s 1%), and corporate partnerships of one kind or another have become more common. Plus, the industry figures you see in articles like this one hardly ever factor in expenses, which—including anything from production, marketing, and artist fees, to venue costs and road crew wages—can add up to huge sums.

The lack of clarity around whether a particular work of music might be worth more or less than before has led to intensely divided opinions. Indie-rock stalwart Damon Krukowski wrote on this site that pressing 1,000 vinyl singles in 1988 gave the earning potential of more than 13 million streams in 2012. Steve Albini, the legendary recording engineer (and nearly as legendary curmudgeon), argued in a speech last year that the Internet essentially burned out the inefficiencies and exploitation of the old system, leaving behind a smaller industry that’s vastly better for artists and listeners.

Louder voices than veterans of the ‘80s and ‘90s underground have also weighed in on the value of music lately. Taylor Swift wrote an op-ed proclaiming “music should not be free” before pulling her music from Spotify. Bono, following U2’s famed free iTunes album giveaway, clarified his support for moving listeners away from expecting free music. “The challenge is to get everyone to respect music again, to recognize its value,” Jay Z said recently, discussing his new Tidal streaming service. “Water is free. Music is $6, but no one wants to pay for music.” Setting aside the water bills many non-moguls pay each month, is music $6? Without a public breakdown of the numbers, those of us who pay for songs and albums find ourselves in a position similar to that of the earliest American consumers of bottled water: There’s always some wag who’ll remind you “Evian” spelled backward is “naïve.”

The shrinking of the record industry, at least, is beyond dispute. Global revenues from recorded music slipped to about $15 billion in 2014, according to the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry; that’s down from an inflation-adjusted worldwide peak of $60 billion in 1996. The United States, the world’s biggest market, took in 2014 revenues of just under $7 billion, according to the Recording Industry Association of America, down from an inflation-adjusted $20.6 billion at the 1999 peak. In other words, using 2015 dollars, the American record industry is slightly more than one-third its size before the bubble burst. That massive drop in revenues has come despite the advent of the iTunes download store, Spotify, and other potential industry saviors. And the decline hasn’t started reversing itself yet—revenues were relatively flat the last several years, according to the RIAA.

So yes, the record industry has had a rough 21st century thus far. Less clear is the economic value of an individual song or album, though details slip out occasionally. During the copyright infringement trial for Robin Thicke and Pharrell’s “Blurred Lines”, for example, lawyers for both sides agreed that 2013’s top-selling digital single worldwide had earned profits—that is, net income after expenses—of nearly $17 million.

In late 2013, Spotify disclosed an average per-stream payout to rights holders of “between $0.006 and $0.0084,” or less than a penny per play. Spotify has called per-stream averages a “highly flawed” way of looking at its value, saying that as more and more people subscribe to the service, everyone will benefit. And to be sure, artists have always received, at best, only a fraction of revenues from their records. In 1983, about 8% of the price of an $8.98 vinyl album went to artists, according to Steve Knopper’s book Appetite for Self-Destruction. When the CD arrived that same year, artists got less than 5% of the $16.95 price. By 2002, when CD prices hit $18.99, 10% went to artists, according to Greg Kot’s Ripped. Download sales cut out the cost of packaging, but artists got only a slightly bigger share of revenues: just 14% of the $9.99 iTunes album download price, according to a David Byrne essay in 2007, or 17% for an artist on one indie label cited by Kot.

Indeed, if measuring the financial ramifications of a track or stream in contemporary times is tricky, figuring out how that compares to records, CDs, or downloads in years past is harder still.

As the bassist for Superchunk and co-founder of Merge Records, Laura Ballance has actively participated in the music industry for more than 25 years. In the book Our Noise: The Story of Merge Records, she’s consistently the one figuring out budgets and keeping track of accounting at the North Carolina indie label that has been home to Arcade Fire, Neutral Milk Hotel, and the Magnetic Fields. So I thought if anyone could tell me how much a recording is worth to independent artists today compared with 10 or 20 years ago, she would be the one.

Ballance was prepared for my call; she’d been looking through old documents. But from CD sales to downloads, and then from downloads to streams, she found, each leap in technology defied exact monetary comparisons. “It’s hard to break it down per song or even per album,” Ballance told me. “For each stream, is that a unit? What’s a unit? When we first started selling records, it cracked us up to use the word ‘unit.’ You can’t even define a unit anymore.”

As it turned out, this problem—comparing the price of vinyl apples to CD oranges, download kumquats to streaming (I don’t know) pomegranates—was a constant one across the history of recorded music. Finding a way around, I decided, it would require some accounting as creative as more than a few songs I’ve heard.

As long as the record industry has had units to shift, what might constitute a “unit” has always been shifting.

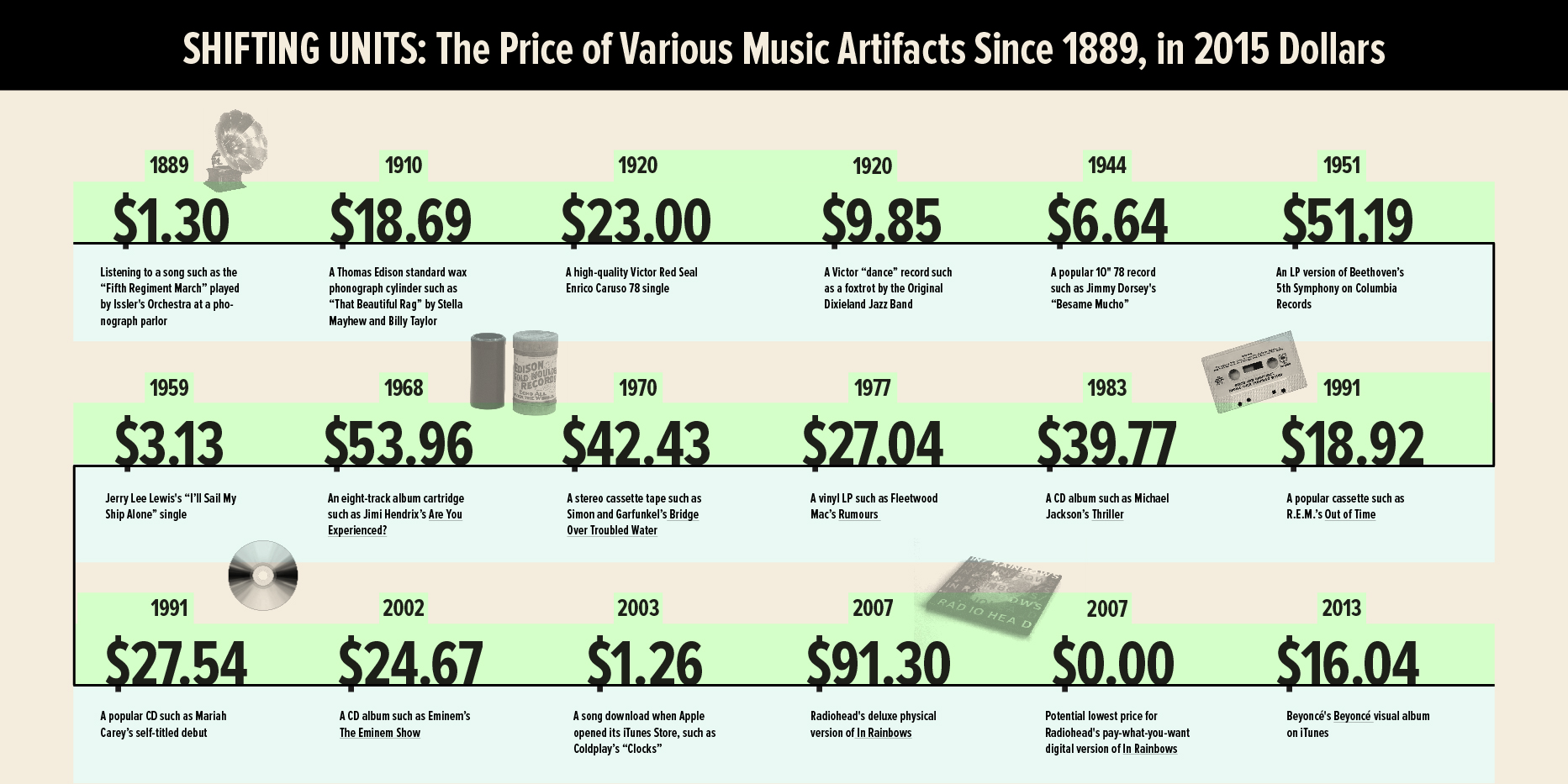

In 1889, when the first “phonograph parlor” opened in San Francisco, saloon patrons could listen to a song through a tube for a nickel. When Thomas Edison began manufacturing wax cylinders of recorded music for home entertainment in the late 1890s, they cost 50 cents each, played at 120 RPM, and could hold only two minutes of music. Loosely speaking, what cost a nickel in 1889 would cost $1.29 today, and what cost 50 cents in 1900 would go for $13.89 today. (Then as now, how much money ever ended up in the hands of musicians remains murky.)

Over the same period, German inventor Emile Berliner was working on his own “gramophone,” which used discs rather than cylinders. He started the Berliner Gramophone Company in 1895, initially selling 7” records, made out of hard rubber, for 50 cents ($13.89 today). By 1906 or 1907, the standard Berliner disc was 10 inches and held up to four minutes of music. This began recorded music’s first format war, between the cylinder-based phonograph and the disc-based gramophone.

Though U.S. listeners still sometimes refer to vinyl record players as phonographs, the gramophone won. A variation on Berliner’s flat discs, developed by inventor Eldridge Johnson’s Victor Talking Machine Company, soon dominated the market. Johnson cultivated a higher-end brand, an appeal that, as the success of expensive Beats headphones has highlighted, can be paradoxically mainstream. Victor’s “Red Seal” series, launched in 1903 in the U.S., found a perfect marriage of marketing and musician. Italian opera singer Enrico Caruso, Red Seal’s signature artist, signified European refinement in middle American homes, while both his tenor vocal range and patient recording style were among the best-suited yet for the era’s technology.

Caruso’s Victor recording of Pagliacci’s “Vesti la giubba” is generally considered the first million-selling record in history. Upon its 1904 release, the Red Seal line’s standard $2 price tag would have been worth $51.46 in 2015 dollars; humbler Victor records sold for 25 cents ($6.43) to 50 cents ($12.84). No less a populist than the oral historian Studs Terkel once recalled how, his father had “brought home a Victor record and ever so gingerly placed it on the phonograph.” His mother, Terkel wrote, “was furious” at the cost. “My father wasn’t much for words. He simply said, ‘Caruso.’”

If Internet radio affects the record industry today, in the 1920s the threat was simply radio. In the face of this technological challenge, Johnson sold control of Victor in 1929—to the Radio Corporation of America, or RCA, which today is owned by Sony. Outside of the latest updates in gadgetry, a bigger peril for record makers was the Great Depression; though it may be tempting to imagine that art is somehow above such concerns, music is as dependent on outside economic forces as anything else. Adjusted to today’s dollars, estimated U.S. record sales tumbled from a high of almost $1.4 billion in 1921 to less than $100 million in 1933. In historical context, then, the past 15 years may have been rough, but they’re not the worst faced by the industry.

After that nadir, the vehicles for recorded music kept evolving. So did the prices. In the late 1940s, as the post-World War II boom lifted the music industry out of its Depression-era crash, Columbia launched the 12” 33 RPM microgroove LP while RCA rolled out the rival 45 microgroove RPM 7”. Both were comparatively high-fidelity products, both were made out of vinyl, and unlike in most format battles, both have managed to share space on record players sold to this day. By 1951, prices for 45s and LPs ranged from 99 cents ($8.94) to $6.45 ($58.23), a situation that Billboard at the time—on the same page as an article titled “Disk Pirates Now Dare Service DJ’s”—deemed “muddled.” Evidently, the problem was not just different price tags for different formats, such as a 45 single versus a double- or even quadruple-album, but also slight variations in what each record label might charge for a recording of, say, Beethoven’s 5th Symphony. Billboard noted, “Many dealers are beginning to wonder whether they are record dealers or bookkeepers.”

As the record industry got to work really moving units, what constituted a unit of music started moving like excited atoms in a quantum state.

By 1977, when the U.S. industry shipped its most vinyl albums ever—a total of 344 million LPs/EPs—it also moved 36.9 million cassette albums and 127.3 million 8-track albums. Three years later, cassettes would overtake 8-tracks, and by 1983 they’d surpass vinyl, following a period of declines that sparked concerns about home taping. Total units wouldn’t regain their Saturday Night Fever-era levels until 1988, not coincidentally the year compact discs moved ahead of vinyl. By 1992, CDs would overtake tapes. Despite steep declines, total annual units of the shiny plastic discs have never fallen behind album downloads; with the rise of streaming as an alternative, they may never.

Other types of units since the late ‘80s include cassette singles, CD singles, download singles, music videos, download music videos, DVD Audio, Super Audio CDs, and ringtones. An RIAA database shows the industry’s more recent revenue streams—such as sync licensing, ad-supported on-demand streaming, and distributions from SoundExchange, a nonprofit that parses digital royalties—aren’t broken down into units at all. Recorded music, according to the RIAA at least, has gone beyond measurable units: becoming, almost literally, priceless. Or is that worthless?

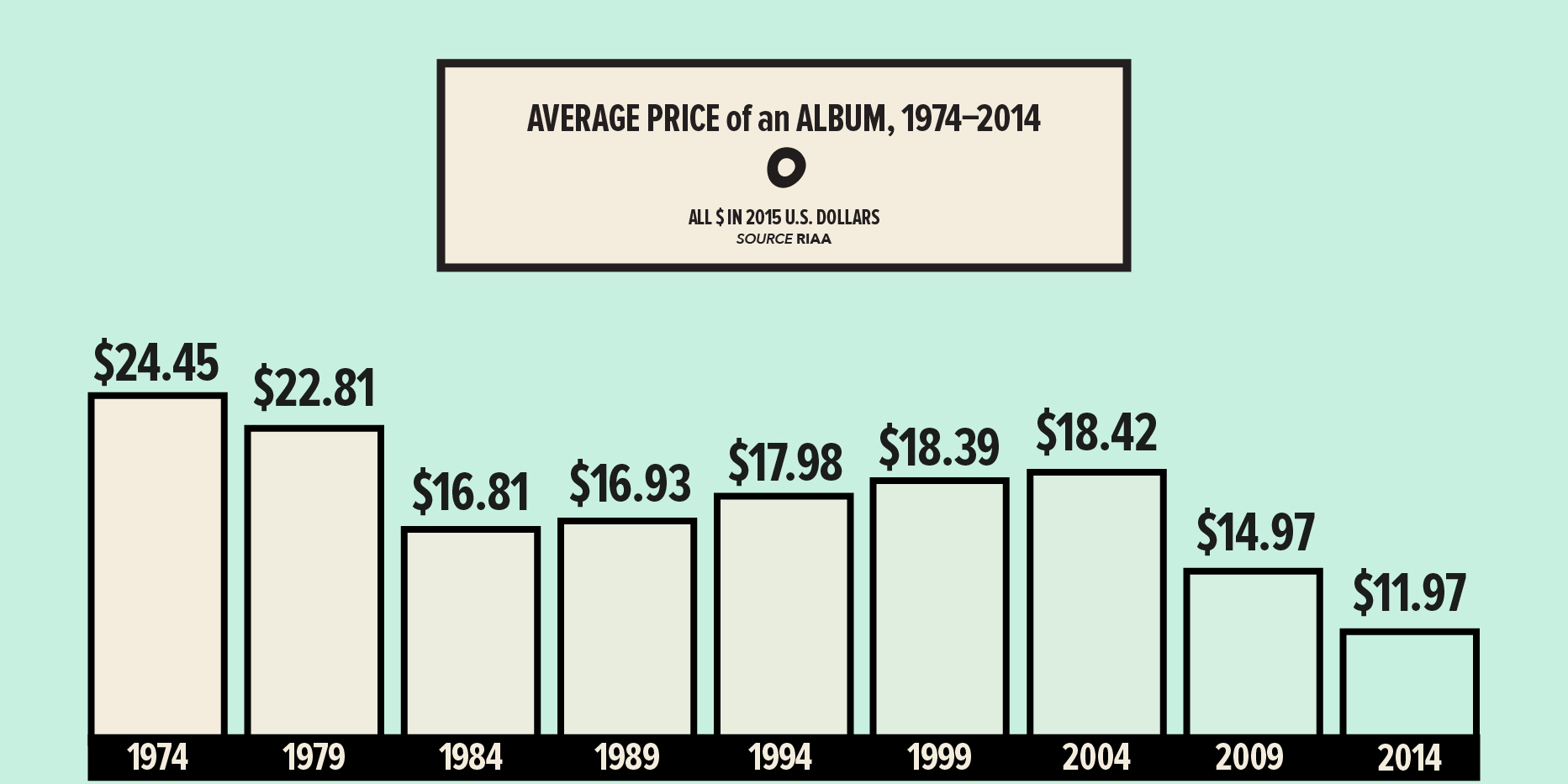

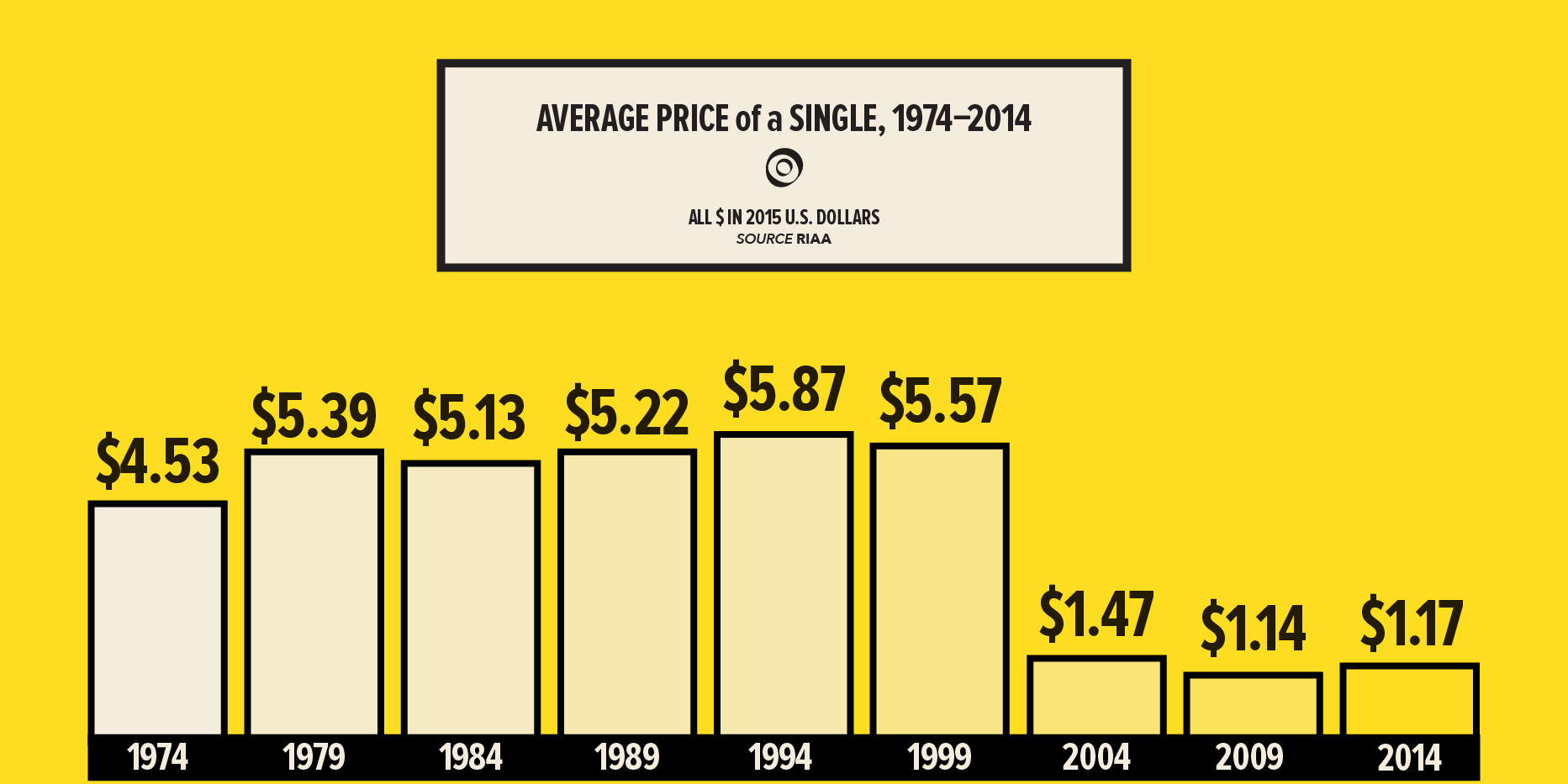

Streaming aside, it’s possible to get a rough measurement of how much the value of an album or single has declined across time. Along with units shipped, the RIAA database tracks annual inflation-adjusted revenues going back to 1973. To get an average for each year, then, you could divide revenue by units. Joshua P. Friedlander, the RIAA’s VP of research and strategic analysis, told me the best way to do that would be to crunch the aggregate numbers for albums across all formats (vinyl, 8-track, cassette, CD, and digital download) and then do the same for singles; if this isn’t exactly apples to apples, at least it’s staying within the same food group.

So: The U.S. record industry’s decline has been steep enough when measured by its total revenue. Broken down by average units, it’s worse.

For albums, the descent was gradual but deep. In 1977, per-unit sales of all albums—vinyl, cassettes, and 8-tracks—averaged $24.81 in 2015 dollars. In 2000, per-unit sales of CDs, cassettes, and vinyl averaged $18.52. By 2014, measuring CDs, vinyl, and downloads, that number fell to $11.97. So an album, as tracked by the RIAA, brings in 52% less in constant dollars than it did in the disco era, and 35% less than it did at the height of the Internet boom.

For singles, the pattern has been more jagged, but ultimately more negative. In 1977, per-unit vinyl single sales averaged $5 in today’s dollars. In 2000, when U.S. singles were scarce and served a niche market, the format—whether on CD, cassette, or vinyl—averaged $5.87. In 2014, per-unit single sales—downloads, CDs, and vinyl—dropped to $1.17. So a single now brings in 80% less than it did at the turn of the century.

Setting aside the particular format, then, albums gross less than half as much, on average, as they once did, and singles bring in roughly one-fifth of their past glories. For comparison, remember that overall revenues in constant dollars are roughly one-third what they were at the U.S. industry’s millennial peak. Units have shifted, all right: into insignificance.

No, this approach doesn’t include streaming, which last year had revenues that topped CD sales for the first time. And there are pretty obvious differences between the formats. Still, as the Times’ Krugman noted at SXSW, even an imperfect metric is better than none. However you try to measure a unit of music across time, you’ll have to use a bit of artistic license.

One more quick point about the data: Adjusting revenues for inflation can also shed light on individual formats, such as the growing vinyl niche. Vinyl albums (including EPs), at $23.86 per unit in 2014, certainly are expensive compared with CDs, which averaged $12.87, or download albums, which averaged $9.79, especially considering the alternative of free, on-demand streams. That’s up from only an inflation-adjusted $15.45 per vinyl album in 1999, compared with $19.23 for CDs. Still, vinyl is actually cheaper than it was in 1977, its biggest year-ever by units shipped and by inflation-adjusted revenue, when the average unit cost $24.81 accounting for inflation. In 2015, even when recorded music’s expensive, it’s cheap.

Live performance has been one way for the music industry to make up the staggering decline in recording revenues. Live shows make up anywhere from 56% of a musician’s income, according to consulting firm Midia Research, to 28%, according to musicians’ advocacy group the Future of Music Coalition. Sales for major concerts in North America totaled $6.2 billion in 2014, according to Pollstar. That’s up from $5.1 billion in 2013, $1.7 billion in 2000, and $1.1 billion ($2 billion after inflation) in 1990. The average ticket price for the top 100 tours in North America was $71.44, up from $25.81 ($38.94) in 1996. One Direction led the way, with $127.2 million gross and an $84.06 average ticket price, followed by Beyoncé and Jay Z with $96 million on an average $115.31 ticket, and Katy Perry with $94.3 million on an average $104.39 ticket.

Performers generally receive far less than these totals, after promoters’ fees and various costs, which can be high. Still, the level of inequality between live music’s biggest moneymakers and everyone else has become vast that it drew notice from an Obama administration economist: In a 2013 speech at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, Princeton professor Alan Krueger, chairman of the White House’s Council of Economic Advisers, said the share of concert revenue going to the top 1% of performers had more than doubled since 1982. “The music industry is a microcosm of what is happening in the U.S. economy at large,” Krueger explained. Don’t hold your breath for an Occupy Madison Square Garden movement.

In late February, I went to see sardonic Canadian punks Single Mothers, whose lyrics are full of mordant references to worth and music: The title of an early single was “Hell (Is My Backup Plan)”, while their 2014 album Negative Qualities includes one song that declares “rock’n’roll’s a sacrifice,” plus another, provocatively titled “Crooks”, that seethes, “If this is living the dream/ Just kill me.” The show itself was a delirious blur, with 29-year-old frontman Drew Thomson hamming it up for his girlfriend cheering him on from the edge of the stage, and I felt privileged to see it at a modest-sized local venue in Des Moines, Iowa. But it was a Monday night in the dead of the Midwest winter. Only 19 audience members paid the $10 admission fee.

When I met with the affably gap-toothed Thomson in the no-frills backstage area, he offered a realistic but relatively upbeat view. He’d left a financially rewarding job in gold prospecting, in a far-flung town with the unlikely name of Swastika, to concentrate on Single Mothers. “It’s definitely still a big game of catchup for us,” he told me, despite being signed to a proper label—Hot Charity, distributed by indie giant XL Recordings—and other trappings of putative success. “Being on the road, we don’t really make any money at all.”

“When I gave up my place at the family business, they looked at me like, ‘You’re making the biggest mistake of your life,’” he continued. “Maybe I am.”

Then again, if Thomson had pursued that line of work, he reasons, he would never have been able to travel so many places or meet so many people. “It all depends on how you look at value,” he said. “I get more of out of the band than I would out of money, anyway. I’m still surprised anybody shows up.”

Our conversation closed on notes of caution. If royalties started coming, Thomson said, Single Mothers wouldn’t know the avenue to access them (“We’re not good with money”). The whole seat-of-the-pants operation could tear apart at the seams any moment (“If our van breaks down, we’re fucked”). Then there’s the reality of the touring lifestyle. This was the band’s fifth show of sobriety after years of the opposite, Thomson told me—a way of saving money, yes, but also a slightly health-conscious means of self-preservation.

Two opening acts and more than two hours later, after midnight, Single Mothers finally took the stage. Not all of us were observing sobriety. I didn’t have the heart to ask where they were spending the night.

But wait: Recordings and concerts aren’t the only ways for musicians to make money.

Publishing—that is, the rights to a song’s sheet-music composition, rather than the finished track—brought in revenues of $2.2 billion in 2013, according to the latest trade group report. That’s relatively flat from an inflation-adjusted $1.9 billion in 2001, the last year for which numbers were available. But treading water is still significant given the precipitous decline in the record industry over a similar period. ASCAP, which licenses composition rights, posted a record-high $1 billion in revenue for 2014, buoyed by streaming. The royalty rates ASCAP and rival BMI collect from online providers such as Pandora have recently become a focus in the courtroom and in Congress. Publishing rights were also at issue in the “Blurred Lines” trial, and they’re what Tom Petty and Jeff Lynne gained when they received after-the-fact songwriting credit for Sam Smith’s Grammy-festooned 2014 song “Stay With Me”.

The history of publishing rights suggests musicians would be unwise to count on those as steady income, though. Music wasn’t included in the first modern copyright law, England’s 1709 Statute of Anne; Johann Christian Bach, who sued successfully in 1773 to remedy that situation, died so deep in debt that his lenders tried to sell his body to medical schools. (They failed.) Though the U.S. Congress started allowing music to be copyrighted in 1831, professional songwriters still found it difficult to scrape by on royalties alone, with one mid-19th-century composer likening the idea to “simple starvation.” Technology complicated the situation once again with the rise of player pianos, eloquently criticized as a “substitute for human skill, intelligence, and soul” by composer John Philip Sousa. After a 1908 Supreme Court ruling that player piano rolls didn’t fall under copyright law because they were mechanical, Congress created the right to what are still known as “mechanical” royalties a year later.

To this day, the rate for publishing sheet music is up for negotiation between songwriters and publishers, with a commonly reported figure in the handfuls of cents per page. That hasn’t improved with inflation. Mechanical royalty rates are based around a rate set by the U.S. Copyright Royalty Board, which adjusts its numbers periodically. In 1976, the rate was 2.75 cents (about 11 cents today). For physical formats and digital downloads, that rose to 9.1 cents for songs five minutes or less in 2009 (about 9.9 cents adjusted for inflation). Streaming rates differ, and ASCAP has been facing off against Pandora in particular for a higher share of revenues. On February 5, the U.S. Copyright Office released a 245-page report calling for a radical overhaul of the music copyright system, with sweeping implications for musical compositions and sound recordings alike.

Another way of cashing in on music is by cashing in on everything but music. Krugman predicted this “celebrity economy” in a 1996 essay. The critic Simon Frith has written that “star-making, rather than record selling,” is the record labels’ primary purpose. Madonna, ever the pioneer, signed the first “360 deal” in 2008, where she and Live Nation would share in the promotion and the earnings from all revenue streams, not just records.

But these opportunities are not limited to platinum-sellers. Starbucks may have stopped selling physical CDs, but as far back as 2012 it commissioned a Christmas album featuring Sharon Van Etten, Calexico, and the Shins alongside Paul McCartney. Flying Lotus has his own radio station on Grand Theft Auto V. Last year’s Adult Swim Singles series spanned from Giorgio Moroder to Tim Hecker, Mastodon to Diarrhea Planet, Speedy Ortiz to Deafheaven, Run the Jewels to Future.

Artists’ fees from such brand partnerships will vary based on a range of factors, but these arrangements show no signs of fading away, particularly as the payout from records keeps dwindling. “Everybody thinks that bands licensing their music is such a bad thing,” Jason DeMarco, VP and creative director of Adult Swim, told me. “But if it’s done with care it can be a good thing for the band and for the brand. It doesn’t have to suck.”

Enigmatic rapper Lil B recently detailed his first-ever brand partnership, with the vegan food company Follow Your Heart for a new emoji app. The radical optimist, who gives away his music for free online, announced the team-up during a lecture at MIT late last year. “I’m not putting ads on my videos,” he said. “The only stream of income I’m making is live engagements with you guys and the companies that support me. I’m beautiful with that.”

Still, artists’ advocacy group the Future of Music Coalition told The Huffington Post a few years ago that only 2% of U.S. musicians’ total income came from “brand-related revenue.” And artist revenues from licensing their music in films, TV, video games, and commercials has actually fallen 22% over the past six years, from an inflation-adjusted $242.9 million in 2009 to $188.1 million last year.

The famous quote that “information wants to be free” is frequently taken out of context. “Information also wants to be expensive,” continued Whole Earth founder Stewart Brand in the very next sentence from his 1987 book The Media Lab: Inventing the Future at MIT. “That tension will not go away.”

In 2012, Jana Hunter of Baltimore dream-pop explorers Lower Dens wrote on her Tumblr: “Music shouldn’t be free. It shouldn’t even be cheap.” When I spoke with her earlier this year, she was a bit sheepish about what she called the “capitalist” presentation of those remarks. She told me, “What I meant to say is we are living in a society where everything is valued, and, within that context, why is music a thing that we have decided we shouldn’t be paying for?” Still, she continued to have pointed views about the music economy.

“What makes it so frustrating for musicians is that if you really try to center your life around making something creatively, then this becomes a huge distraction and it comes into direct conflict with what you’re trying to do,” she said, referring to the complexity of the business side in the time of streaming. “It derails you creatively.”

She expressed a concern that music, which prior to Edison was practically inseparable from rituals and other social functions, takes on a more fleeting value in a streaming setting. “We are living in a time where the things that are presented to us are presented as very transient, very temporary,” she told me. “Streaming is definitely a way of reinforcing that. You have a temporary context with music, and then another piece of music, and then another piece of music, and you don’t have a tangible, long-term relationship with that.”

Temporariness of some sort has been a norm across the history of recorded music. The business has always been messy. But as someone who buys records—and still hoards a massive iTunes collection—I could see her point.

I had originally thought to contact Merge’s Laura Ballance partly because of a few lyrics from Superchunk’s most recent album, I Hate Music, where label co-founder Mac McCaughan sings, “I hate music/ What is it worth?” The next lines are, “Can’t bring anyone/ Back to this earth.”

Which is true enough. But while we’re still above ground, music can help us understand others, it can help us locate ourselves, it can help us mourn in those moments when we want to breathe life into someone once again. Pioneering electronic composer Pauline Oliveros has created a number of pieces that work well for gatherings such as memorials, “where people need to relate to one another without words,” she told me.

But how does it work? How does music achieve that healing effect?

“Well, I don’t know,” Oliveros admitted, with a long, warm chuckle. “And I don’t know if it does. People have to say so.” As with my attempts to define music’s economic cost, I’d spoken with an expert and been left to come up with my own answers.

We create the value of music through a sort of community consensus, whether in terms of its emotional impact or its monetary worth. As units of music have become difficult to price, they’ve also lost their economic value—so I agree with a recent Future of Music Coalition op-ed arguing that “the music business has a transparency problem.” Would more detail about dollars and cents restore the music economy’s spirit? Maybe. The industry has recovered before, and there are reasons for optimism, but ultimately music and business, though inextricable from each other, aren’t the same.

Music could be worthless and, for some of us, it would still be priceless. That’s why it’s worth so much. [Pitchfork]