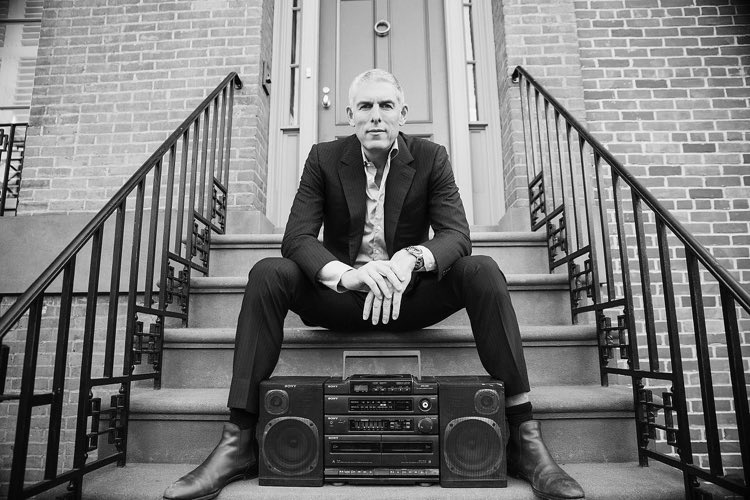

One February afternoon, Lyor Cohen shows me around the soundstage at YouTube Space LA. The new facility, located on the site of what was once a Hughes Aircraft plant for building helicopters, is one of nine that parent company Google has built around the world to encourage the creation and evolution of user-generated programming. For a 57-year-old man who was plastering Snapchat with videos and pictures of his emergency hospitalization for a pulmonary embolism a few months ago, Cohen looks as vigorous as a panther.

“I don’t need to take it slow,” he says when asked about his health. “In fact, I’m accelerating. I’m moving hard.”

Indeed, Cohen’s medical emergency was just the first in a recent string of life-changing events. Last summer, the former chairman/CEO of Warner Music Group married Christie’s executive Xin Li, a former model and basketball player from China. The opulent affair — his third wedding, held at his summer house in Sag Harbor, N.Y., with a surprise fireworks display arranged by the couple’s friend, Wendi Murdoch — was well covered by the fashion and society pages. But the biggest news came in the fall when Cohen opted to leave 300 Entertainment, the boutique music company he co-founded with great fanfare in 2012, to join YouTube as its head of global music.

That YouTube reached for a brand-name music executive for help isn’t all that surprising: Streaming leaders Apple Music and Spotify have brought in Jimmy Iovine and Troy Carter, respectively, while Questlove functions as Pandora’s in-house guru and “artist ambassador.” What is surprising is YouTube’s selection of Cohen, a record exec whose reputation is more brawler than bridge builder.

It’s a big job for Cohen and a nervously watched development, pairing the most controversial man in the music business with the most controversial company in the streaming world. The hugely influential platform, a behemoth claiming more than 1 billion users worldwide and 1 billion hours of video viewed per day, is locked in a long-standing and seemingly intractable war with the music industry over money and control of content. And since Cohen joined YouTube at the end of September 2016, the music business has run wild with speculation as to whether his presence will inflame or calm tempers.

“Lyor may have an impact for them in other areas,” says Irving Azoff, chairman/CEO of Azoff MSG Entertainment, who formed the Global Music Rights group to address online music use. “But as for rights negotiation, YouTube can spin it any way they want, but the reality is that they’re the reason that paid streaming hasn’t exploded. There is a huge value gap in consumption versus revenue.”

The industry has long claimed that music’s popularity has significantly fueled YouTube while the service’s payments to artists and copyright holders have lagged. According to one industry executive, YouTube accounted for nearly 18 percent of the 6 billion streams racked up by a leading boy band in 2016, but accounted for only 5 percent of its payments for streaming. A well-established singer-songwriter who tallied 917 million streams, says the executive, collected 10.4 percent of them on YouTube, but the service accounted for only 4.5 percent of his revenue.

The hard-charging Cohen has always been a love-him-or-hate-him proposition. His biggest boosters include artists he has worked with, like Run-D.M.C., De La Soul and Ja Rule, who credit him with hard work and pugnacious representation. Says the rapper-turned-podcaster N.O.R.E., who has worked with Cohen and whose show, Drink Champs, enjoys a strong following on YouTube: “Lyor always repped the culture and put hip-hop first. If he is able to similarly elevate online television, the results will be incredible. He knows it’s the kids who drive this economy.”

From his earliest days as an executive at Russell Simmons’ groundbreaking Rush Productions and Def Jam Records, Cohen has come on like gangbusters, with even Def Jam’s own publicist likening his initial style to that of “a brute” and a “Doberman.” In 2012, he left his biggest job, head of WMG’s record operation, after clashing with new CEO Stephen Cooper.

Yet he has demonstrated over and over again that he gets the tough jobs done — that he is a relentless, in-your-face fighter and artist advocate who sees losing as an unpardonable sin, a failing surpassed only by not getting paid. With YouTube’s negotiations over new licensing agreements dragging on and labels and artists continuing to complain that the service pays too little for royalties, does injecting Cohen into an already strained relationship with the music business make sense? A string of month-to-month extensions has served as a negotiation placeholder, but record company executives who have worked with Cohen see his presence as a new and potentially disruptive wild card. “YouTube has no idea who he is or what his style is,” says one.

That kind of jab has followed Cohen throughout his storied and stormy career, and he has mastered the weave and counterpunch. “I don’t know about all that behind-the-bushes rap,” he says of anonymous critics. “Would the industry prefer a nonscrappy career employee, or someone who got into the boiler room and did the work? Was [legendary Time Warner CEO] Steve Ross a scrapper or a bridge builder or both? I don’t know. All I do know is that I love this industry and want to continue to contribute.”

YouTube is no stranger to Cohen’s aggressive advocacy. In fact, it has been on the receiving end of it. In 2006, when Universal chief Doug Morris was threatening to sue YouTube out of existence, WMG gave the video site a big boost by going in the opposite direction, negotiating a use agreement with the company and urging Morris and other label executives to take a more open approach to the new service than they had with Napster. But the honeymoon ended after Universal and then-Sony-BMG followed WMG’s lead — and received better deals. Angered, Cohen demanded a similar improvement from YouTube co-founder Chad Hurley. When it wasn’t forthcoming, Cohen continued to harangue and pursue Hurley — both over the phone and in person — so aggressively that one former Warner exec says that in one meeting, he “nearly reduced Hurley to tears.” (Hurley and his partners are no longer with YouTube, having sold their interest to Google in 2006.)

For all the hand-wringing at the record companies, YouTube has a very different take on Cohen’s new role. He’s not here to negotiate a new agreement with the labels — that task will likely remain with YouTube CEO Susan Wojcicki and chief business officer Robert Kyncl. Cohen has been brought onboard to advise YouTube on what artists and record companies want and to help develop new programs and tools for promoting music and careers.

Kyncl, to whom Cohen reports, says he hired him as part of an effort to make YouTube a better resource for music and build a closer relationship with the industry. Cohen’s job is to teach a company dominated by engineers what labels and artists want and to change the service accordingly. “When you’re developing these products, you have engineers working on them,” says Kyncl. “But it’s really helpful to have someone who understands it from the artist and label perspective. Someone who can say, ‘Here’s what’s valuable, here’s what works.’ ” He hopes artists, publishers and labels will come to see Cohen as “your guy on the inside, asking the questions you would ask yourself.”

If nominating Cohen as an ambassador is an unusual idea, the biggest gamble may be his. To take the job he left 300 Entertainment, the label he founded in 2012 with an eye toward mining data and social media for marketing opportunities, and in which he continues to hold a majority stake. A disagreement with his 300 partner Todd Moscowitz over the direction of the label led Moscowitz — who had worked with Cohen at Island Def Jam as well as WMG — to leave 300 and start his own label, Cold Heat Records, with Universal. Though Cohen describes 300 as a project he values dearly, designed “as a contrarian move to prove that a small, well-financed company can be meaningful to the artistic community,” he couldn’t resist a position with the potential for industrywide impact.

Cohen likens his job with YouTube to an earlier decision to leave Def Jam, where he had spent his entire career, to run WMG. “I went to Warner because I wanted to contribute to the decisions that were being made on a macro level. And this is sort of the same journey. This is an important platform and company that is in many ways going to shape how an artist and label engages with fans.”

And how did YouTube come to decide Cohen was the person it was looking for? He may have been the only record executive with whom the company had a close and frank relationship: In 2012, Google invested $5 million in 300 Entertainment. Whether YouTube was intrigued by Cohen and how he had fought for WMG a decade ago or just looking to gain insights into the music business, Kyncl soon developed an appreciation for Cohen’s candor. “We had a breakfast in New York and he gave me four or five things that were critical,” he says.

Cohen was also careful enough to never ask YouTube for special treatment for 300 Entertainment artists like Fetty Wap and Young Thug. It wasn’t long before an appreciative Kyncl became convinced that bringing Cohen inside could be a boon for YouTube. “I realized that that’s the kind of voice we need in our company. I wasn’t looking for a ‘yes man.’ ”

During his years in the record business, Cohen evinced an unusual rapport with artists in no small measure because he can speak frankly and focus on helping them achieve fame and fortune. His opening message to YouTube reflects that experience: He wants the people who design the service to start looking at it the way performers and music companies do, as a tool for their commercial success. He notes, for example, that while Google and YouTube have touted their transparency and ability to provide instructive data, the company needs to recognize that artists have a different set of priorities. “Transparency is great,” he told them. “But numbers one through 10, an artist wants to be rich and famous. Then, 11, they want transparency.”

Being rich and famous is clearly within Cohen’s own comfort zone. Born in New York but raised in a Los Angeles mansion once owned by Chico Marx, he recently bought a 24-foot Greek revival townhouse in New York’s West Village from Chipotle founder Steve Ells for $11.4 million, which is less than what he made five years ago when he sold the Upper East Side townhouse where he raised his son and daughter, Az and Bea, for just under $25 million. Cohen is particularly pleased that the West Village house is within walking distance of YouTube’s new Chelsea offices. He doesn’t have a typical day and says he has yet to do much music industry outreach, having spent about 90 percent of his time since joining YouTube on internal issues. Focused on getting an intimate feel for the operation — with 70 Google offices in 50 countries, he has no idea how many people are in YouTube’s global music operation — he spent the week that we met bouncing between the Los Angeles and San Bruno, Calif., offices and recently made the Zurich and London hubs his first international stops. The Swiss office, home to 1,600 engineers, is where YouTube manages its Content ID program, which identifies copyrighted material, and is also working on ticketing and merchandising initiatives. “The majority of my effort is to work with the product and engineering team to help design products that are going to be useful for the artists, labels and creative community,” he says.

Cohen wants to develop promotional systems that allow labels to test viewer reactions to records and allow for promotion. Indeed, he knows how hard it is for a new artist to get noticed in a world of unlimited noise, and he sounds more like he’s working for a music label than YouTube when he suggests, “We could help them determine if they have a hit or a stiff if we could jack the system.”

“You have to talk to the labels,” says Cohen, “and give them the data that allows them to be well informed. Does a video get dragged into a person’s list? Does it get listened to in its entirety? We’d like them to think of us as a valuable tool in developing and breaking artists.”

While Cohen is busy trying to get his hands around a worldwide, tech-driven operation, his new co-workers are going to have to adjust to a boss who operates on a separate wavelength. YouTube is dominated by engineers. “I think people want the authentic Lyor,” he says, but finds the company’s style “significantly different” from the music industry. When one of his marketing executives jokingly refers to the office as a “back-to-back culture” (as in back-to-back meetings), Cohen admits that’s not how he likes to do things. “I prefer the mutant mistakes,” he says. How that shakes out after the honeymoon period remains to be seen: This is a company where virtually no one communicates by telephone; Cohen, by comparison, has found that it is really difficult to yell at someone for 45 minutes in an email.

There aren’t any rough edges evident as Cohen — unfailingly complimentary and enthusiastic — leads a video conference with a half-dozen YouTube employees in four offices to review marketing, promotion and performance lineups for South by Southwest in March. He is already familiar with each of the dozen artists who will be performing at the YouTube space at the Copper Tank Event Center. “I’m looking forward to being there,” he tells them.

Queried after the meeting as to when the music industry can expect to see some of the programs and innovations that he is helping YouTube develop, Cohen predicts it will be in the second half of this year. For music copyright holders, YouTube remains both a bonanza and a bone of contention. It has been key in developing and breaking artists from Justin Bieber and Pentatonix to Rae Sremmurd and Migos, rap groups that recently dominated the Billboard Hot 100 thanks in large part to fan-crafted memes and videos. But the industry has long viewed the ad-based YouTube’s pay rate as substandard, and has been threatening to deliver the service a body blow by pushing Washington, D.C., for changes in the Digital Millennium Copyright Act’s “safe harbor,” a key Internet provision protecting YouTube from copyright challenges over user-generated videos incorporating music.

Plus, YouTube is now operating in a world where subscription services like Spotify and Apple Music are producing the most meaningful income for copyright holders. The company counters that argument by pointing out it paid $1 billion to music copyright holders for the 12 months that ended last October, and that the number will continue to multiply in the coming years if it is given a chance to develop. Google, including YouTube, earned $19.4 billion in revenue in 2016 and the company says it aims to grow by taking as much as it can of the $239 billion spent annually on TV and radio advertising — and that music’s popularity with its users means sizable future payouts. “It’s not a matter of if,” says Kyncl, “but when.” “We’d like to shift the dialogue so it’s not simply around the deal,” admits Cohen. And while music executives may welcome the new tools, they’re unlikely to take their eye off the bottom line. “Everybody would love a real program,” says Global Music Rights CEO Randy Grimmett. One label executive sees little chance of avoiding a hard-fought battle over a new contract: “I do think they know they’re going to war.”

Though Cohen admits he has had little direct industry contact since coming to YouTube, he’s confident that having “someone from their community helping communicate, shepherd and evangelize what it is to be a record person” will strike the right chord. “It has only been positive,” he says when asked what he has heard back from the industry. “But I’ve stayed only listening to positive, you know what I’m saying? People may have other opinions. But this is how I feed my family: breaking artists.”

This article can be found on billboard.com